-

-

-

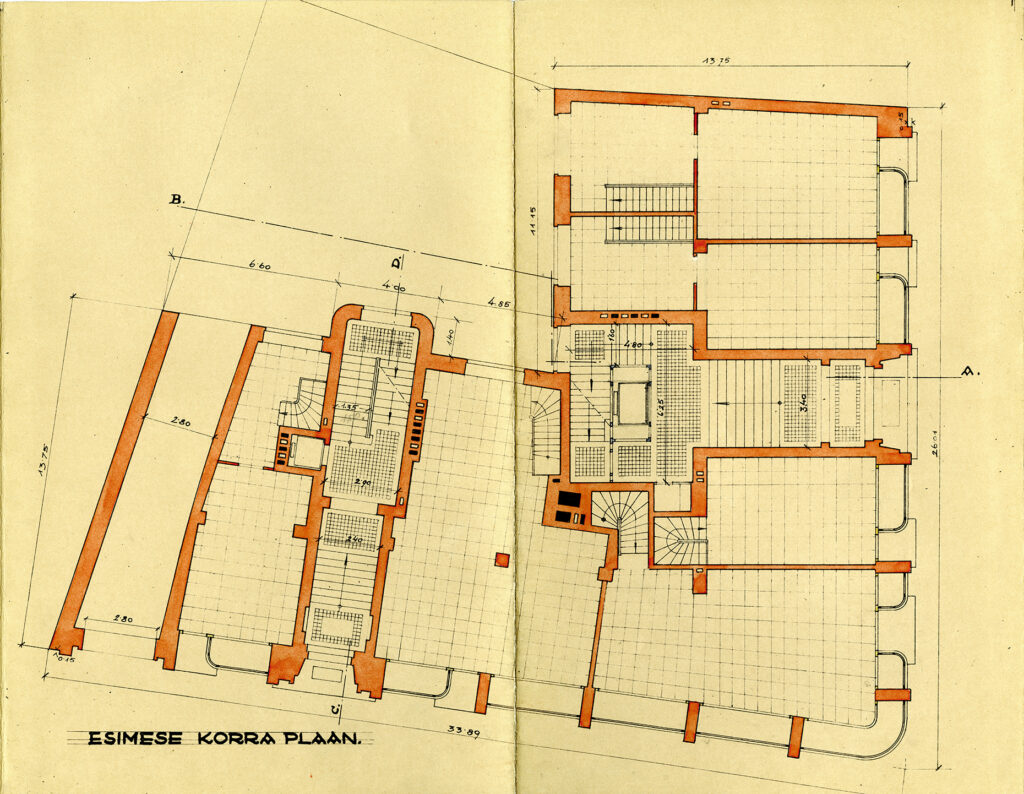

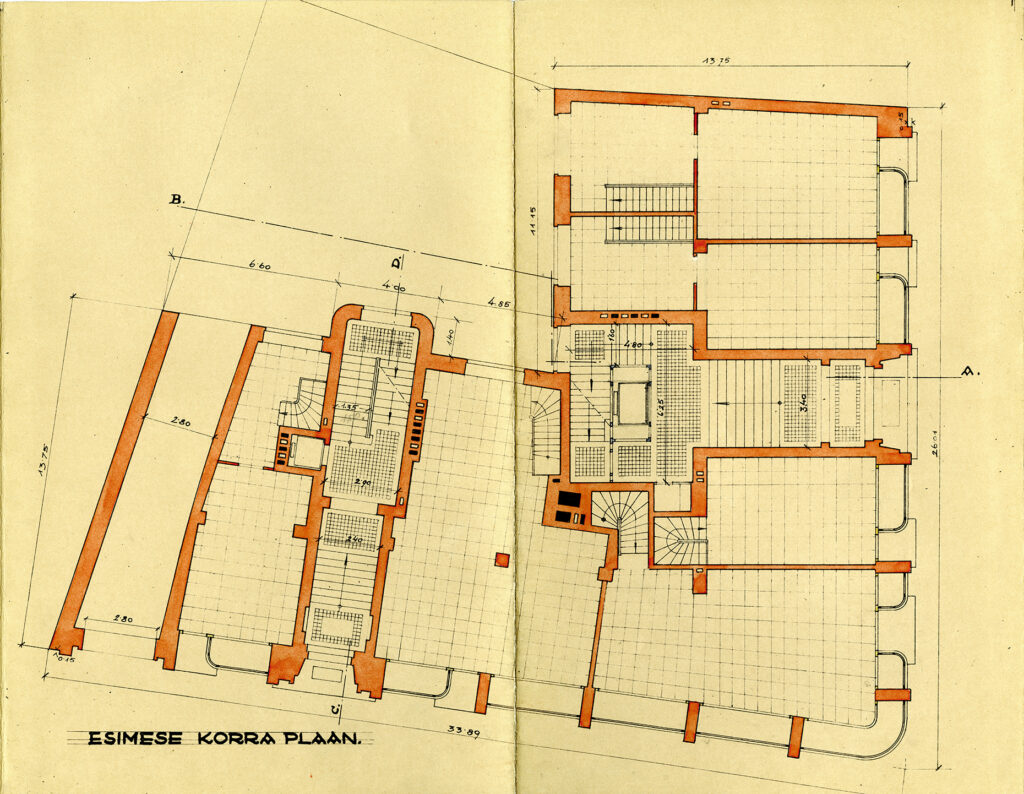

First floor plan

-

-

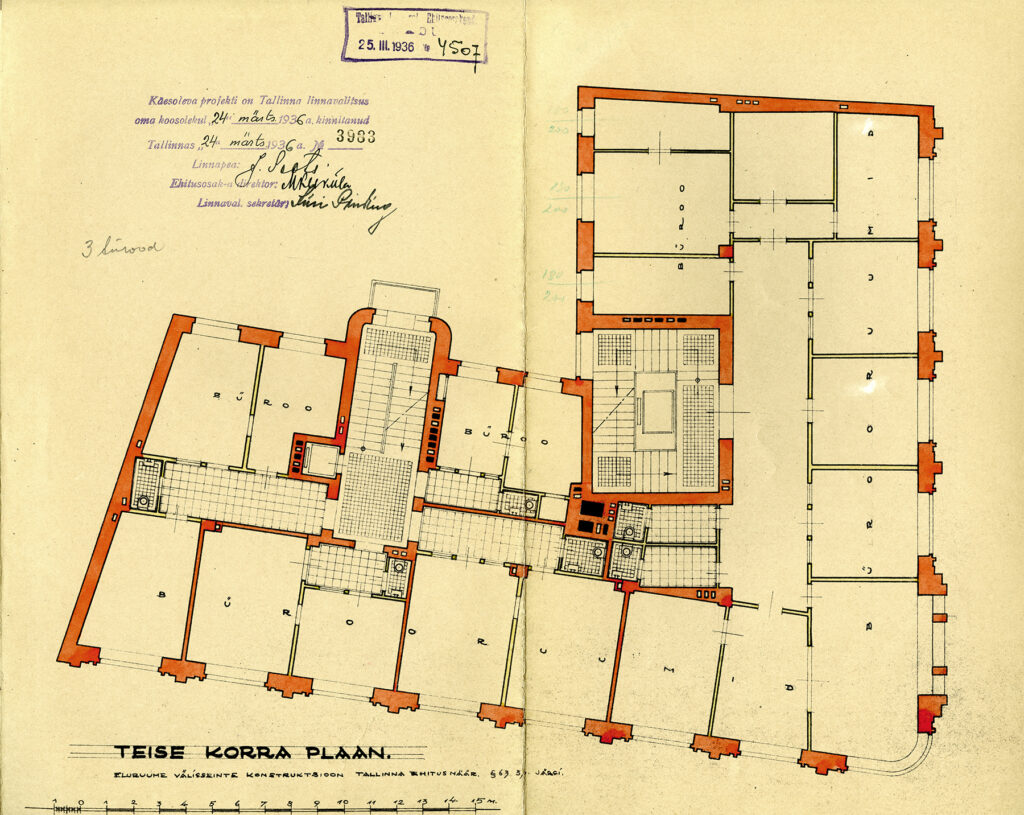

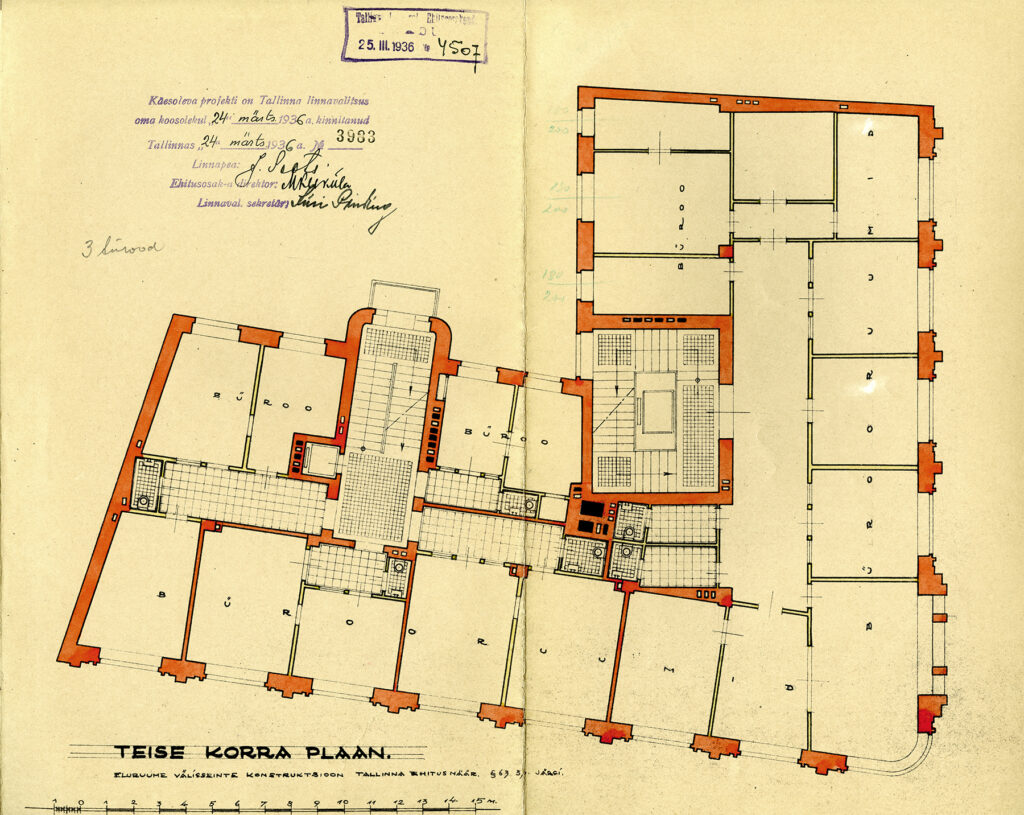

Second floor plan

-

-

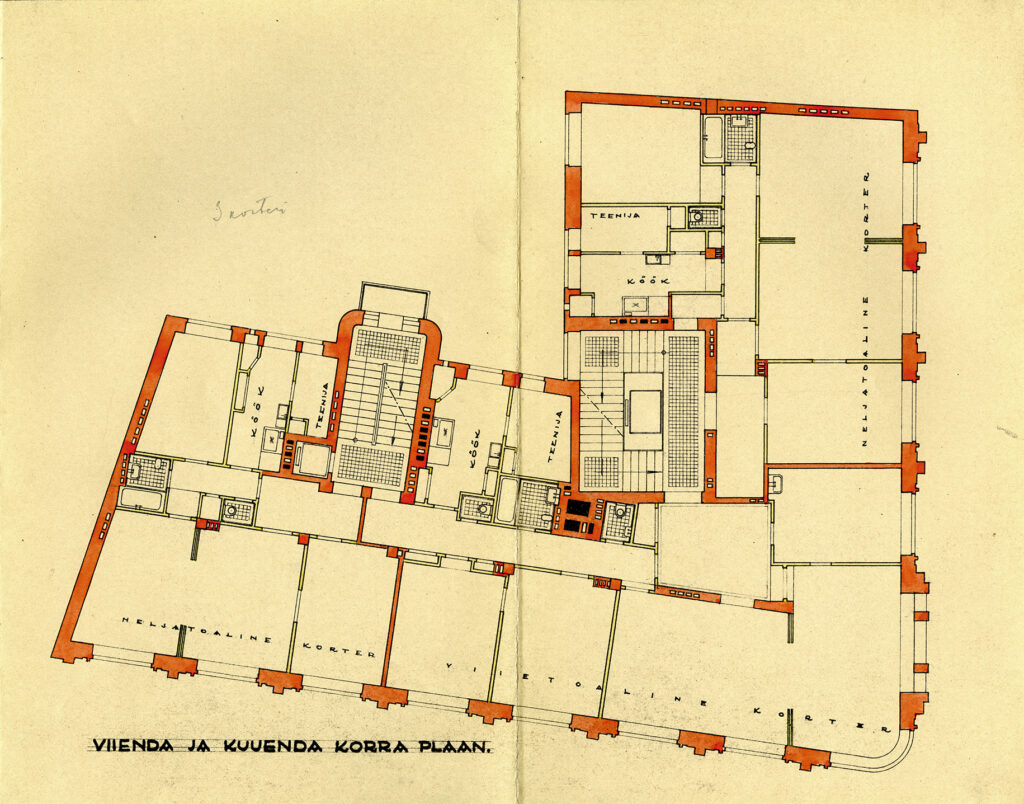

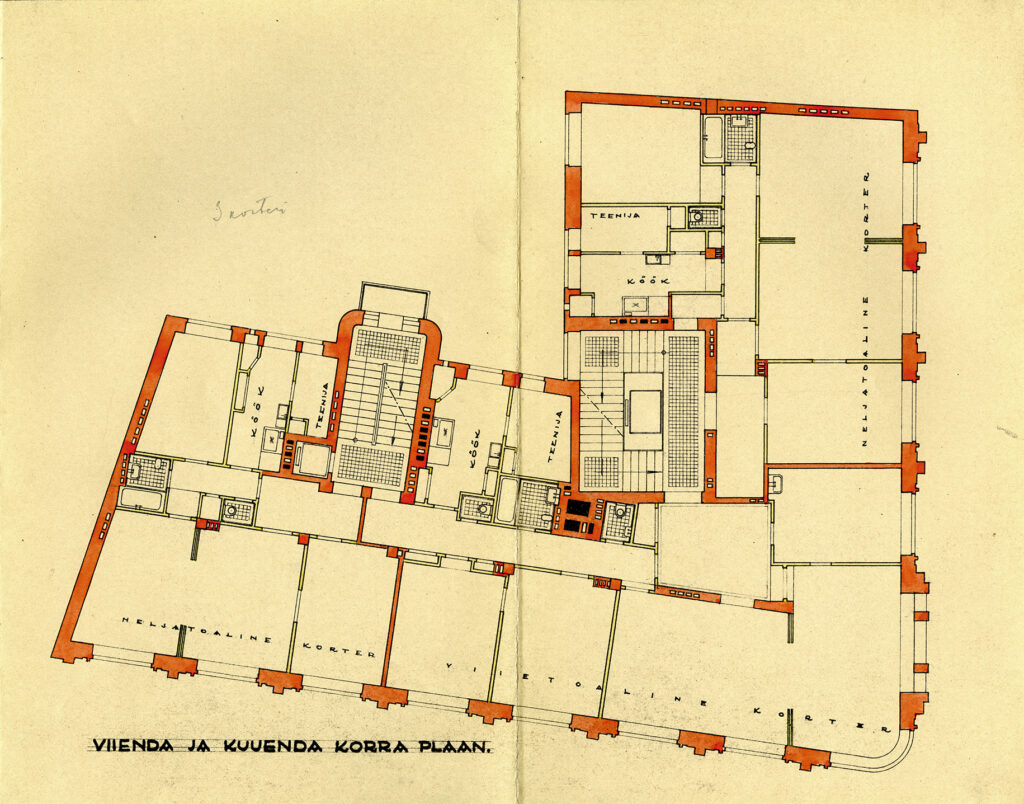

Floor plan of fifth and sixth floor

Eugen Sacharias, 1936. EAM 2.2.320

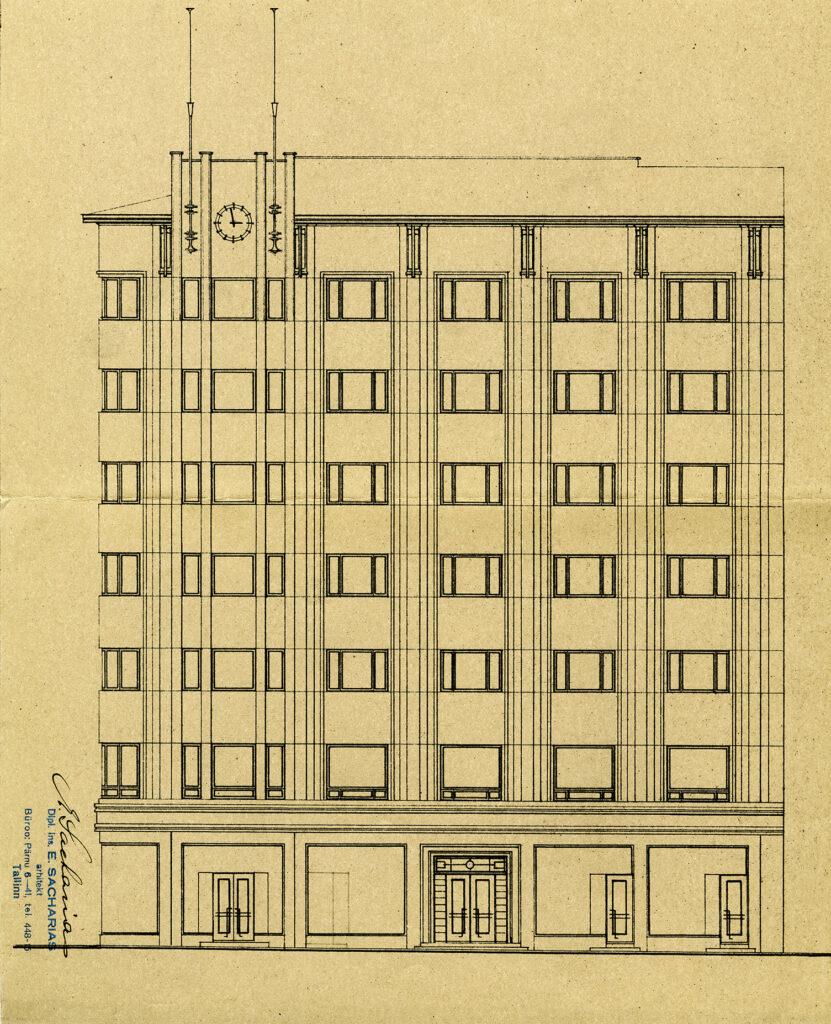

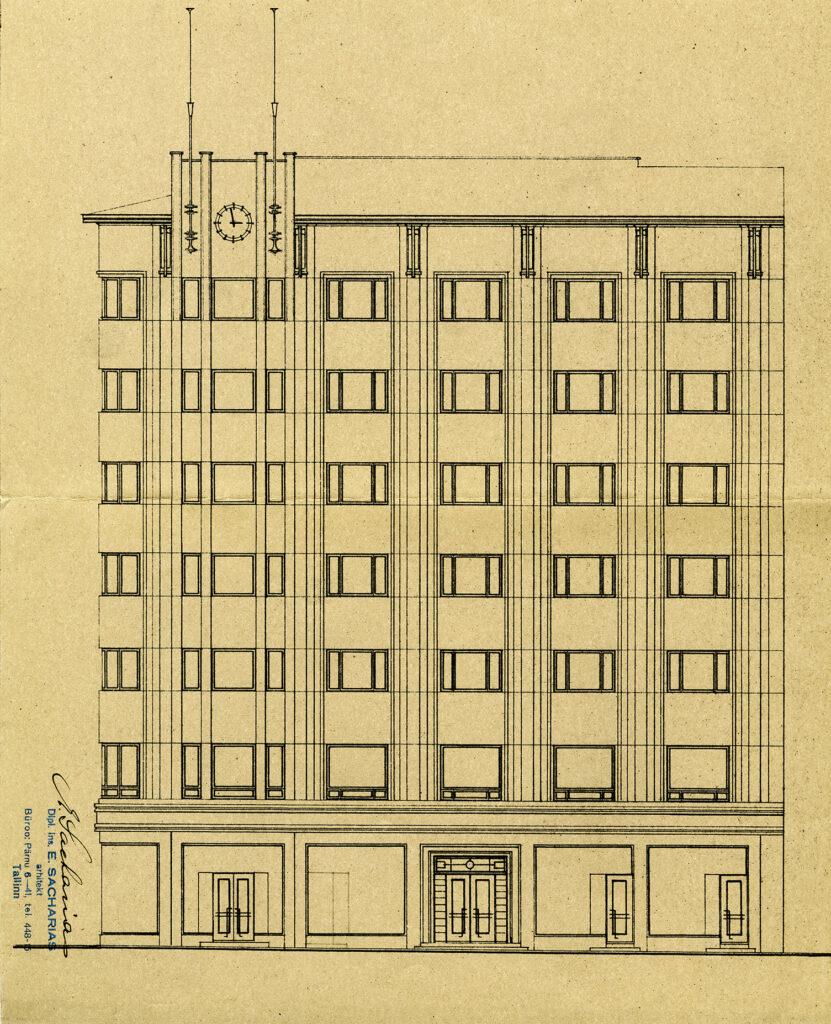

Office and Residential Building at Pärnu Road

The seven-storey building on the corner of Pärnu Road and Väike-Karja Street is one of the most representative rental houses built in the second half of the 1930s in the center of Tallinn. The project was commissioned from Eugen Sacharias (1906–2002) by the association “Elamu”. On the ground floor there were and still are business premises, on the first floor offices and on the higher floors there were multi-room apartments with all amenities, bathrooms and maid’s rooms. As there were several doctors among the tenants at that time, this house has also been called the so-called doctors’ house. On the seventh floor of the building were the offices of the architect Sacharias.

The Baltic-German architect Eugen Sacharias was born on April 21, 1906, who studied at the Technical University of Prague in 1925–1931. As a talented and enterprising young architect, he first helped Eugen Habermann design the so-called Urla House on 10 Pärnu Road, after which he founded his own office. In the following ten years almost 40 apartment building projects were completed. That shaped the representative visual of Tallinn as the capital. In 1941, Sacharias left to Germany with his family and ended up in Australia, where he continued to work as an architect in a construction company. In April 1991, Eugen Sacharias’ 85th birthday was celebrated with an exhibition in the lobby of the Library of the Academy of Sciences (now the Tallinn University Library). The exhibition was curated by art historian Mart Kalm. This was the first exhibition of the Estonian Museum of Architecture, founded three months earlier.

Text: Anne Lass

-

-

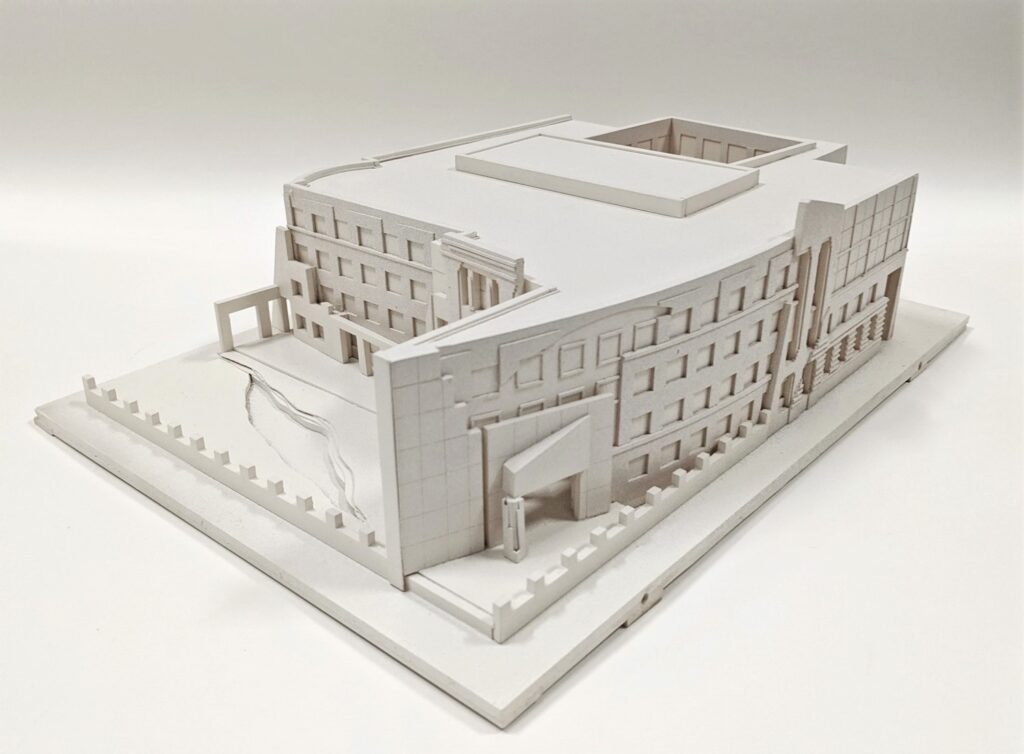

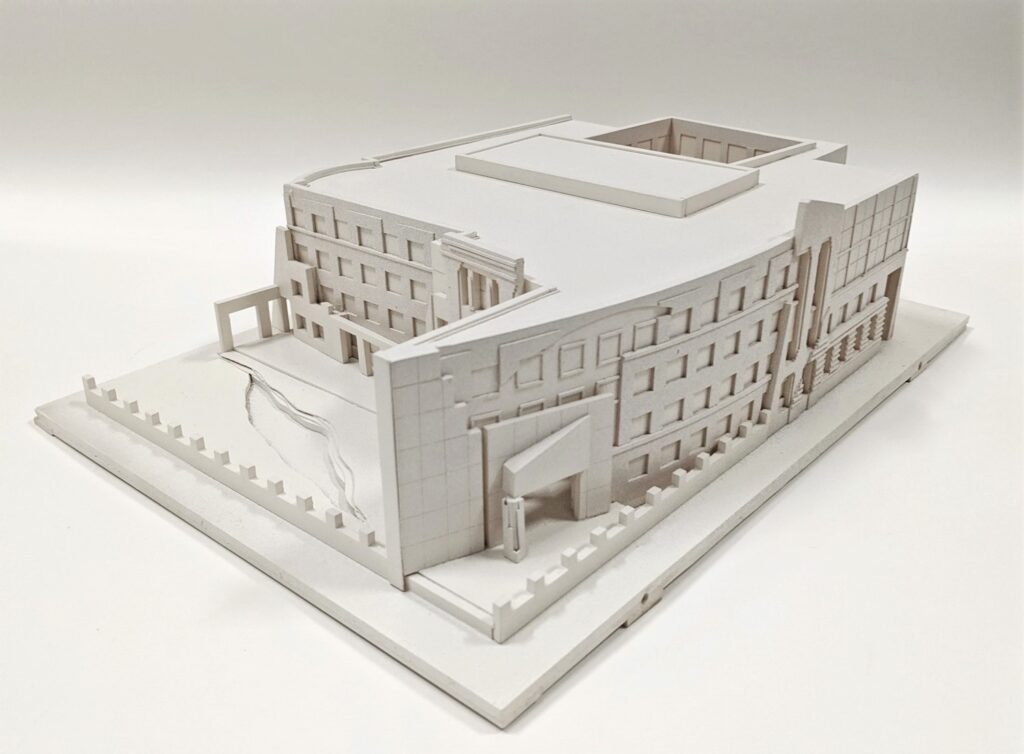

Tallinn Secondary School of Science (Tallinna Reaalkool) annexe, competition entry “Koolimaja” (III prize)

Marika Lõoke, 1981. MK 227

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Extension to Tallinn Secondary School of Science

Tallinn Secondary School of Science (Tallinna Reaalkool) will be 140 years old this year. The school was founded in 1881, in the same year an all-Russian architectural competition was organized to obtain a schoolhouse project. The competition was won by Max Hoeppener (1848–1924), a Baltic German architect from Moscow. Hoeppener was assisted in the construction project by Carl Gustav Jacoby, a Tallinn city engineer at the time. The first building designed for a school building in Tallinn was completed in 1884.

A century later, in 1981, a competition was held for a vision of the extension of the school building. The location of the new addition was to be set on the current sports field. 13 works came to the competition. The first prize was given to the architects Vilen Künnapu and Ain Padrik for the project named “Kivirünta” (EAM 41.1.10), the second place went to Kullervo Kliimand’s work “Poiss” (“A Boy”). The third prize was shared by Kiira Soosaar, Siiri Kasemets and Jüri Karu’s competition work “Imelik” (“Strange”) and “Koolimaja” (“School House) by Marika Lõoke. In the magazine Ehituskunst, the editor of the magazine, architect Ado Eigi, describes it as follows: “ In addition to the attractively playful, postmodernist façades maintained at a good professional level and the expressive plan solution, the competition work “Koolimaja” (author Marika Lõoke) also suggested an interesting corner solution together with the M. Gorky named Library building (now Tallinn Central Library – A.L.).” A year later Marika Lõoke also received the 3rd prize at the competition for the new building of the Kreutzwald State Library. The library competition model belonging to the collection of the Museum of Architecture can be seen in the soon-to-open exhibition at the National Library. Together with several other models, the author donated them to the museum in 2017. See also “Architecture. Second-third, 1982–1983.” Text: Anne Lass

-

-

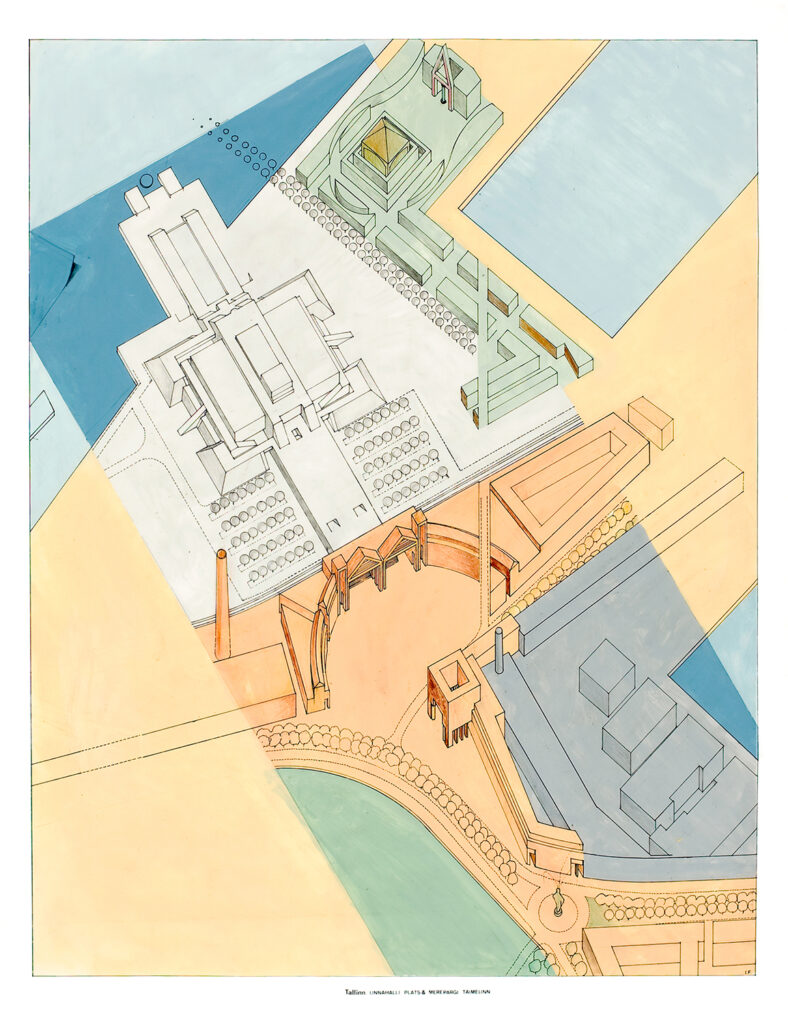

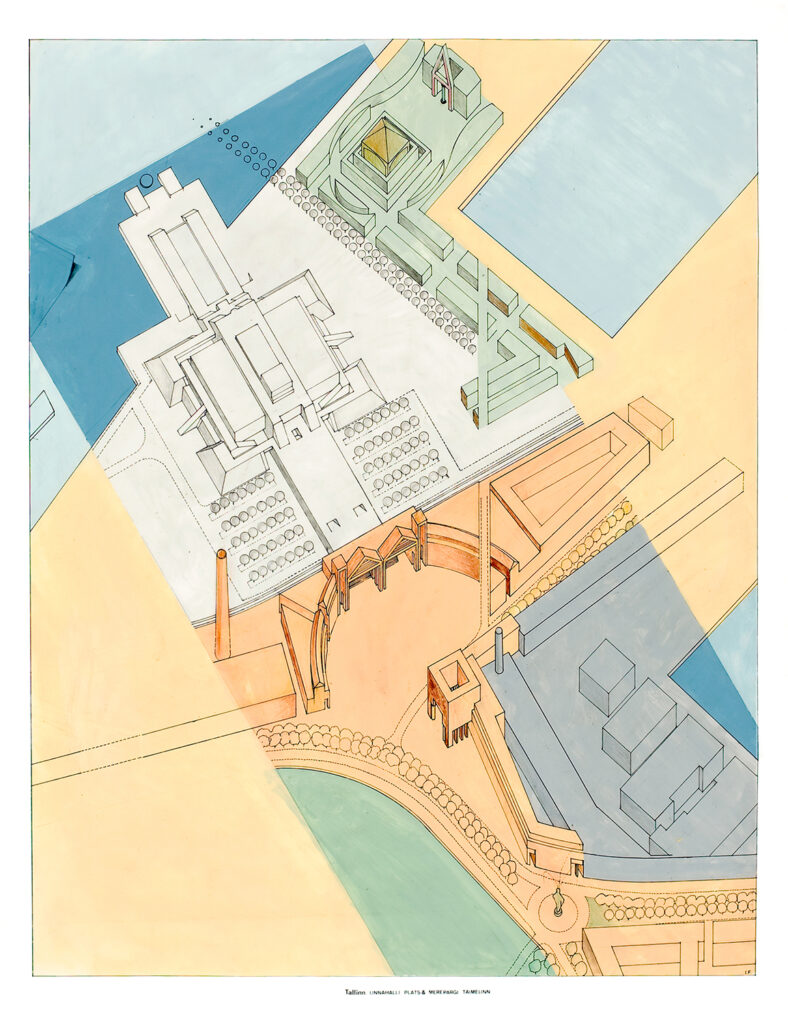

Linnahall Square and the Merepargi Taimelinn (the Plant City of the Sea Park)

Ignar Fjuk, 1982. EAM 5.4.61

Linnahall Square and the Merepargi Taimelinn (the Plant City of the Sea Park)

Tallinn Linnahall was built during the building frenzy which preceded the 1980 Olympics, but the surroundings were not developed as planned. The area between the power station and the commercial port was cleaned of the production residue from the factories and the concrete blocks that were laying around. At the same time, discussions became louder about granting people in the city access to the coastal zone, which had thus far belonged to the border zone and been managed by large factories. Ignar Fjuk designed a green park area to surround the Linnahall, which also included a place for architectural forms – gates and pavilions. He presented his vision in the group exhibition ofthe Tallinn School, which took place at the Tallinn Art Salon in 1983. This illustration made in ink and gouache was given to the museum as a gift by the author in 2002. Text: Sandra Mälk

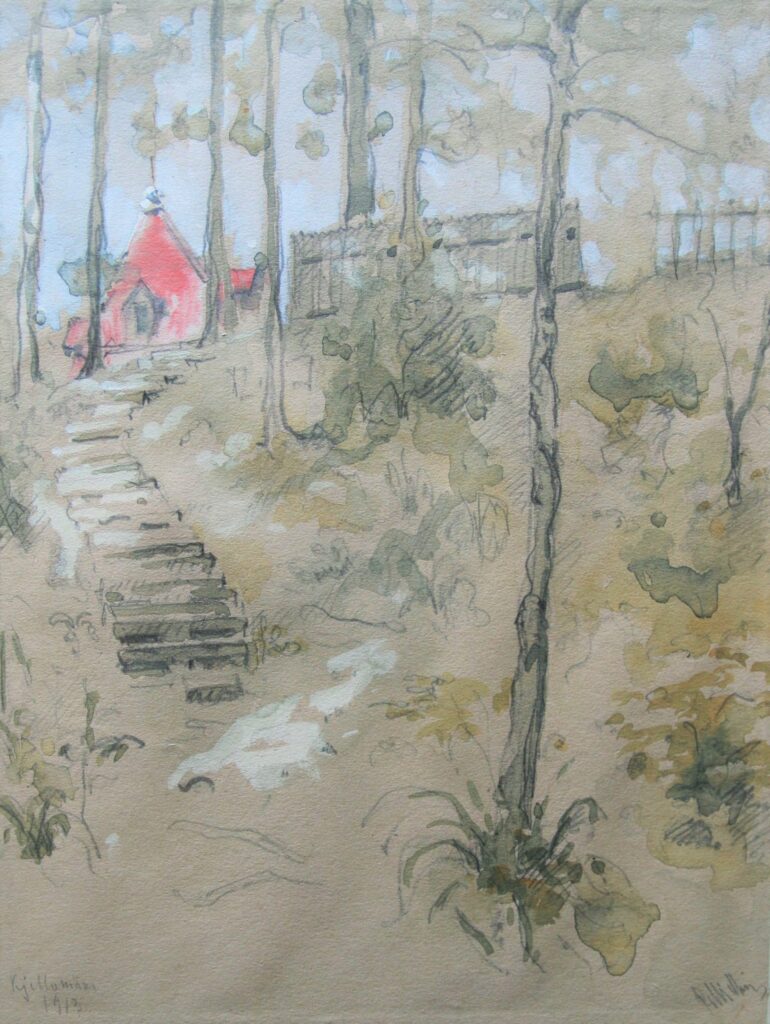

Paul Mielberg, 1913. EAM K 37

Kellomäki Motif

Paul Mielberg, architect and lecturer at the University of Tartu 1922–1940, was born on March 18, 1881 in Tbilisi (Georgia). His father, Johannes Mielberg from Viljandi County, was the director of the Physics Observatory in Tbilisi. From 1899 to 1901, Paul Mielberg studied at the Riga Polytechnic Institute, afterwards at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, where he received a diploma of Artist-Architect in 1910. After graduating, Mielberg worked for several well-known St. Petersburg architects. From 1911 to 1918, he was the chief architect of the Swedish architect Fredrik Lidval (Karl Burman also worked as Lidval’s assistant a few years before), participating in the design and construction of St. Petersburg Art Nouveau landmarks such as the Azov-Don Bank and Count Tolstoy’s tenement house. In 1922, Mielberg came to Tartu and became an associate professor of construction studies at the University of Tartu and also an architect of the university. More than a dozen buildings belonging to the university were built or reconstructed according to his design or supervision. On December 18, 1996, art historian Andres Kurg wrote a review article about Paul Mielberg’s role as an architect of the university in Postimees “About the Architect who designed the university and the Tähtvere district”.

Paul Mielberg left Estonia in 1941 and died in 1942 in Germany.

In 2010, the architect’s daughter Olga Kompus donated her father’s watercolors from 1911–1913 to the museum. Kellomäki, a popular summer resort and excursion destination in Karelia on the Gulf of Finland, about 40 km from St. Petersburg, is a sketchy romantic landscape with Art Nouveau handwriting. For moody views of the Kellomäki, see the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ACNcIEXRIM

Text: Anne Lass

-

-

Model of the Paide Cultural Centre

The model of the Cultural Centre in Paide, 1986. EAM MK 91

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Cultural Centre in Paide

The Paide Cultural Centre was designed in the Estonian Rural Construction Project in 1984–85. The architect Hans Kõll and the designer Rein Üts are the authors of the project. The stained glass window of the façade was designed by the artist Kaarel Kurismaa. The unique interiors of the cultural centre are the work of interior architects Tiiu Pai and Taimi Rõugu, stained glass windows are designed by the artist Kalev Roomet. The representative building on the corner of Pärnu and Tööstuse streets – where the new social center of Paide was to come – was completed on 1987. On January 1, 1988, the magazine “Sirp and Vasar” (The Hammer and the Sickle) published photos of the new culture house on the front page and wrote:

“The dream of the people of Järva County has come true – on December 27, the cultural house of Paide district was opened. The biggest in Estonia, the best in Estonia. Quickly and well-built, given to the customer half a year before the deadline – this should be the perestroika momentum for other constructions as well, especially for cultural objects.”

Despite this and the building being criticized at the time for its scalability and restless façade design it was named the best building of 1988. The Paide Cultural Centre (now the Paide Music and Theater House) has so far functioned in its original use and preserved its authentic appearance and interiors. In 2016, the building was declared as a cultural monument. The 1:100 model of the Paide Cultural Centre was made by Rein Koster and Ants Anari, it was added to the museum’s collection in 2001. Text: Anne Lass

-

-

Riga Estonian Students’ Society, 1909

Riga Estonian Students' Society, 1909. EAM.16.4.71

Riga Estonian Students’ Society

The Riga Polytechnic Institute became one of the most important providers of technical education in the 19th and 20th centuries, where well-known Estonian architects, engineers, industrialists and others studied. At that time, it was one of the closest schools for studying architecture next to the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. The Tallinn Technical School (Tallinna Tehnikum) was established not until 1918. By the new century, there were already many Estonian students at the Riga Polytechnic Institute that several corporations were formed to unite the students. The picture probably shows the founders of the Riga Estonian Students’ Society (later the Student Society Liivika), which was formed in 1909. These young students are future architects, engineers and industrialists who have greatly influenced Estonian society. According to their educational background, they were later called “riialased”, the Rigans.

Sitting Left to the Right: architect Anton Soans, Anton Uesson – the later mayor of Tallinn and Karl Treumann (Tarvas). Standing Left to the Right: Karl Feldmann (?), Architect Aleksander Bürger, banker Heinrich Väljamäe, engineer Konstantin Zeren, lawyer Voldemar Tomson, Peeter Sisask (?). The photo was purchased from an antique shop in 2020. Text: Sandra Mälk

-

-

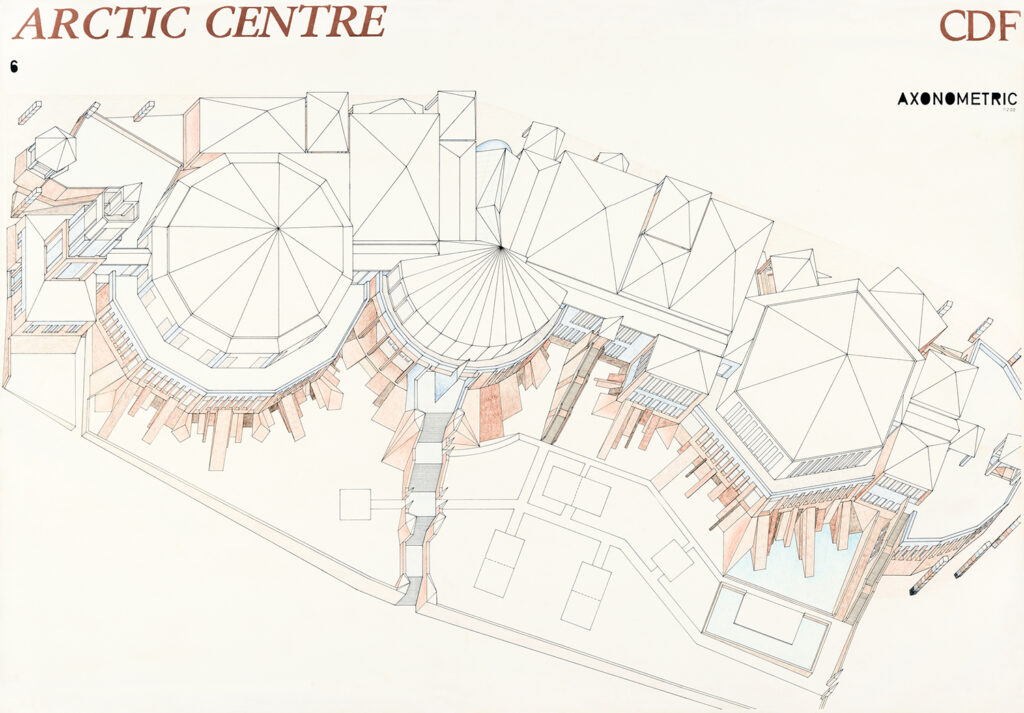

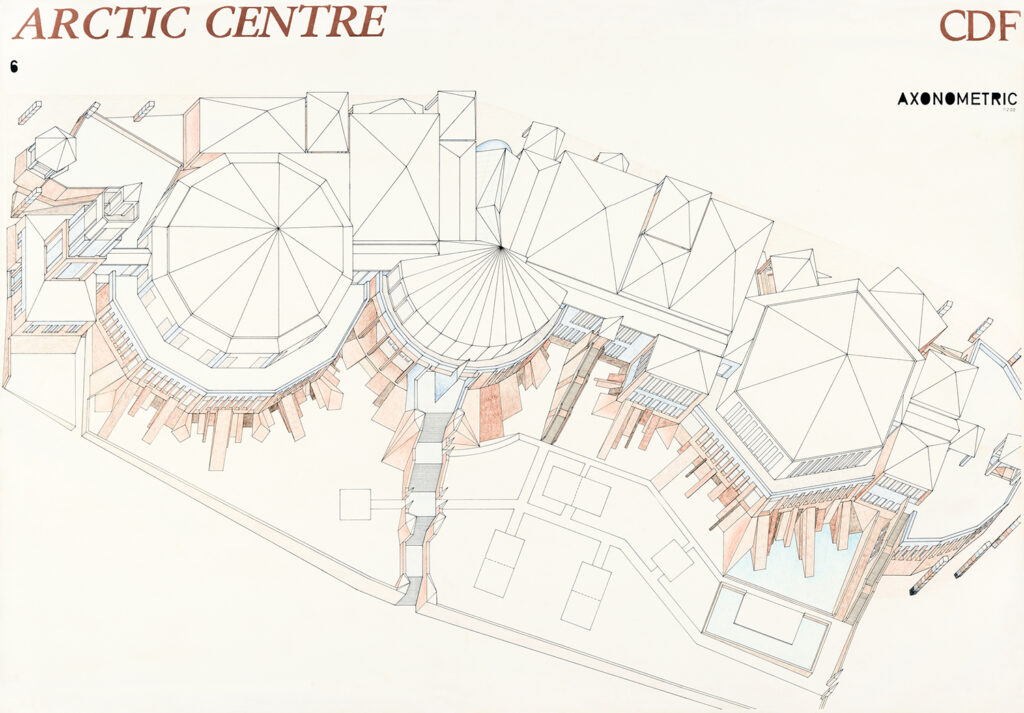

Competition entry for the Arctic Centre in Rovaniemi, 1982

Andres Alver, Leonhard Lapin, 1982. EAM.5.4.70

Competition entry for the Arctic Centre in Rovaniemi

Eight countries in the northern hemisphere, including the Soviet Union with three entries from Estonia, took part in the international architectural competition the purpose of which was to introduce Arctic nature, history and culture. The designers for the entry “CDF” drew inspiration from Caspar David Friedrich’s painting The Sea of Ice. The shape of the building, which houses two different museums – the Arctic Museum and the Provincial Museum of Lapland – bears direct resemblance to ridged ice. The idea of being dominated by Nordic nature is further emphasised by the complex being situated on the steep riverbank that follows the natural relief of the plot. Nine large-format drawings altogether with the axonometric projection shown here were brought to the museum by the authors in 2008. Text: Sandra Mälk