-

-

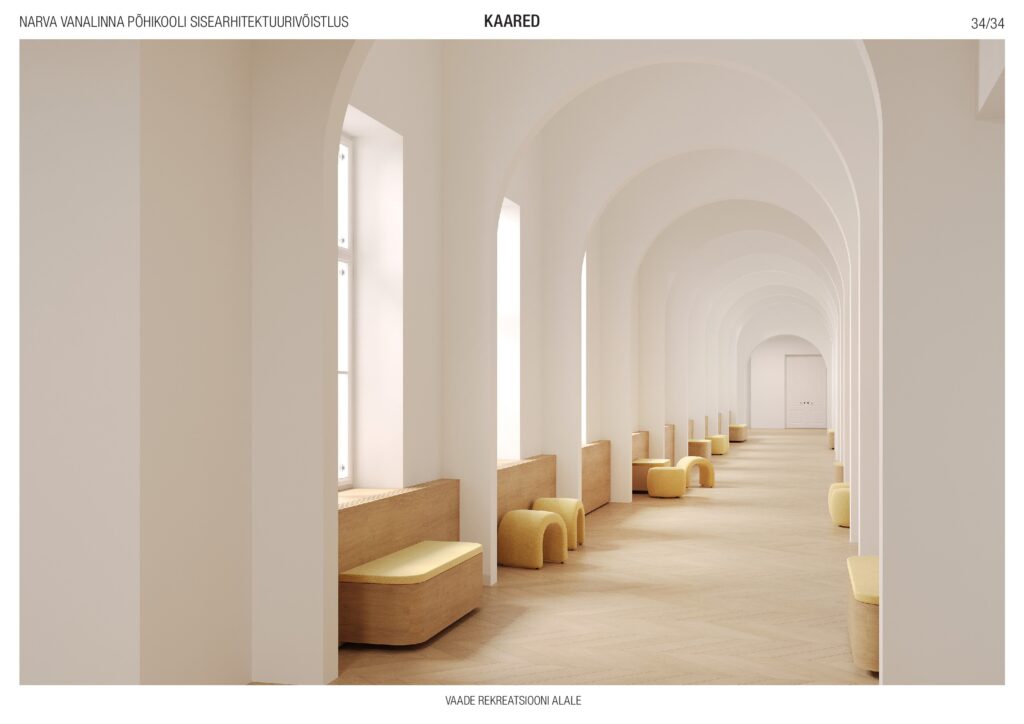

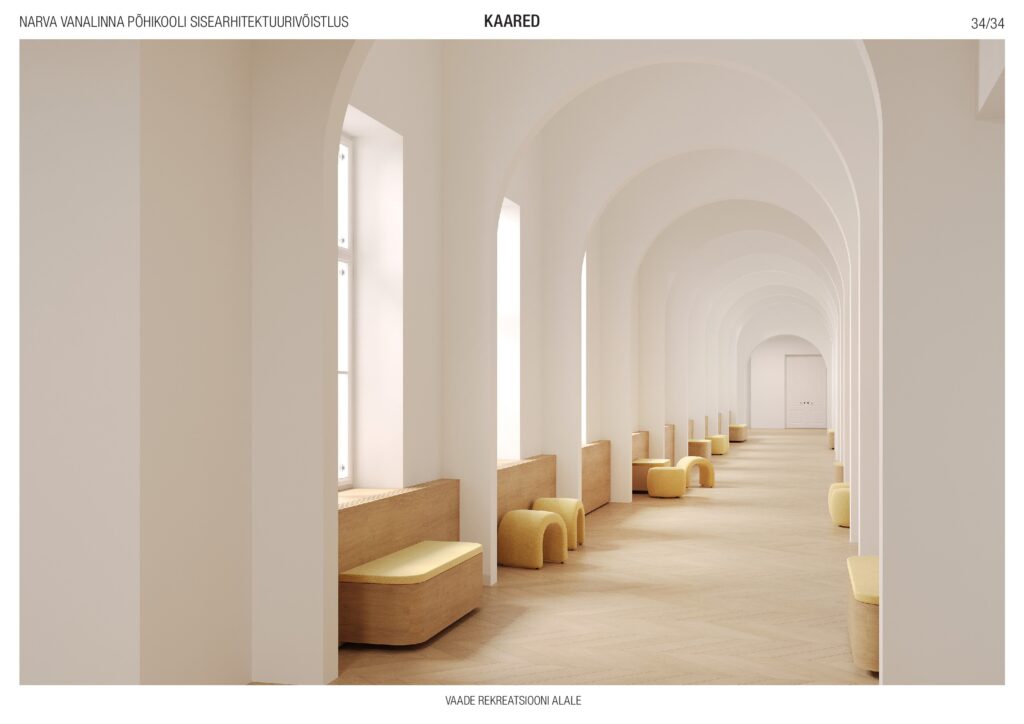

Excerpt from the winning entry “Kaared” in the Narva Old Town State School interior design competition (2024). Studio Argus OÜ and Arhitekt Must OÜ. EAM Dk 987

-

-

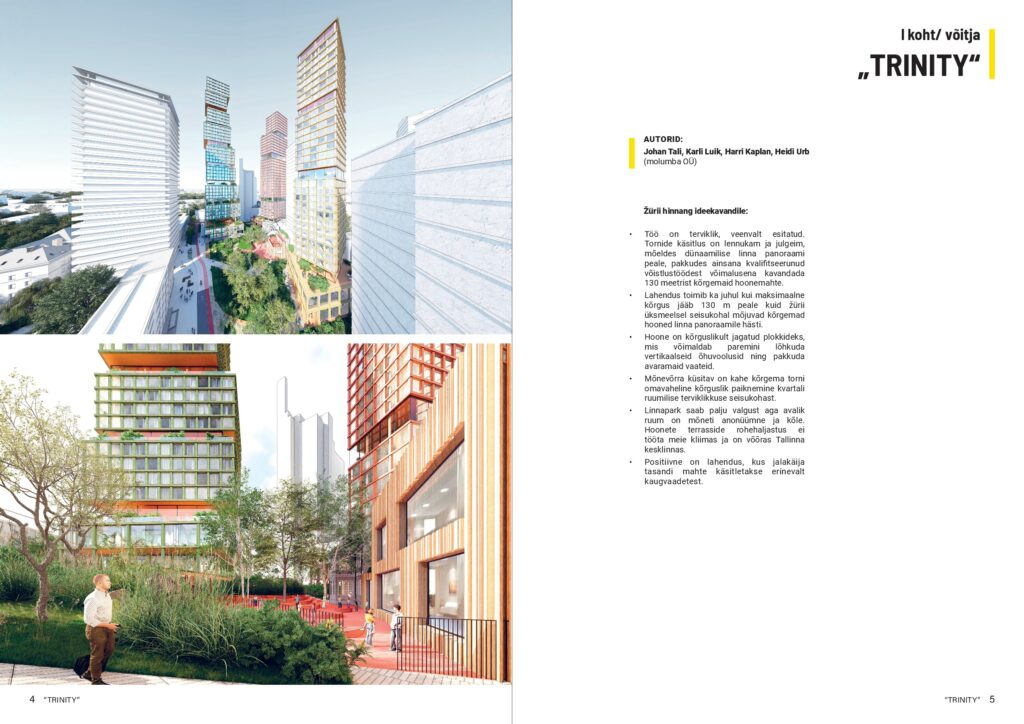

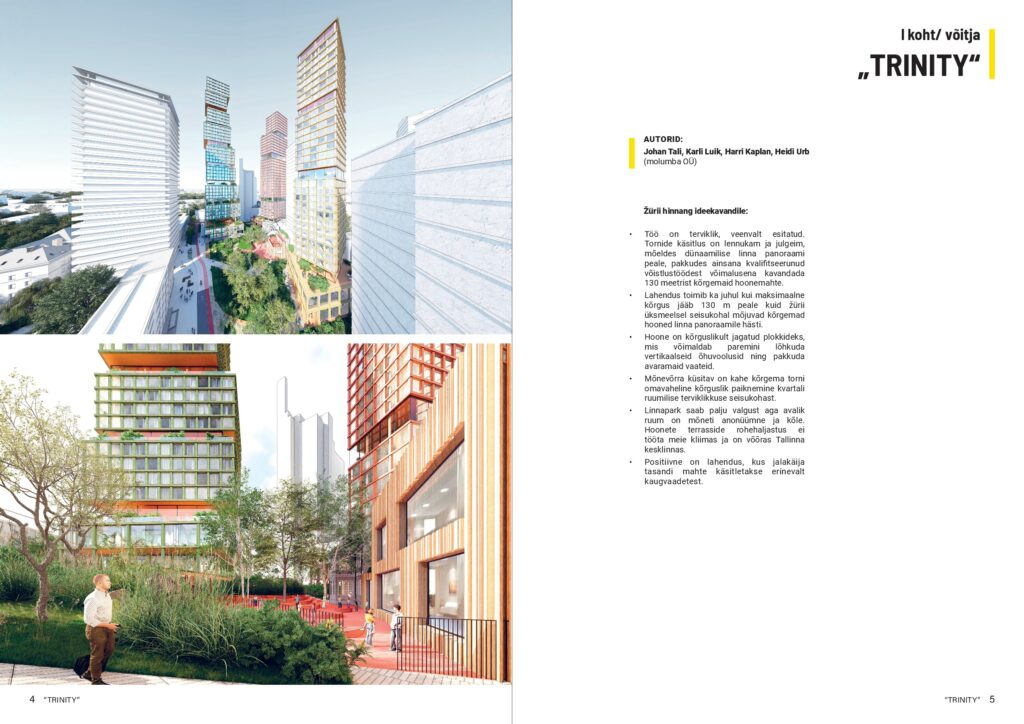

Excerpt from the protocol of the Maakri Quarter architectural competition (2024). EAM Dk 1072.1

-

-

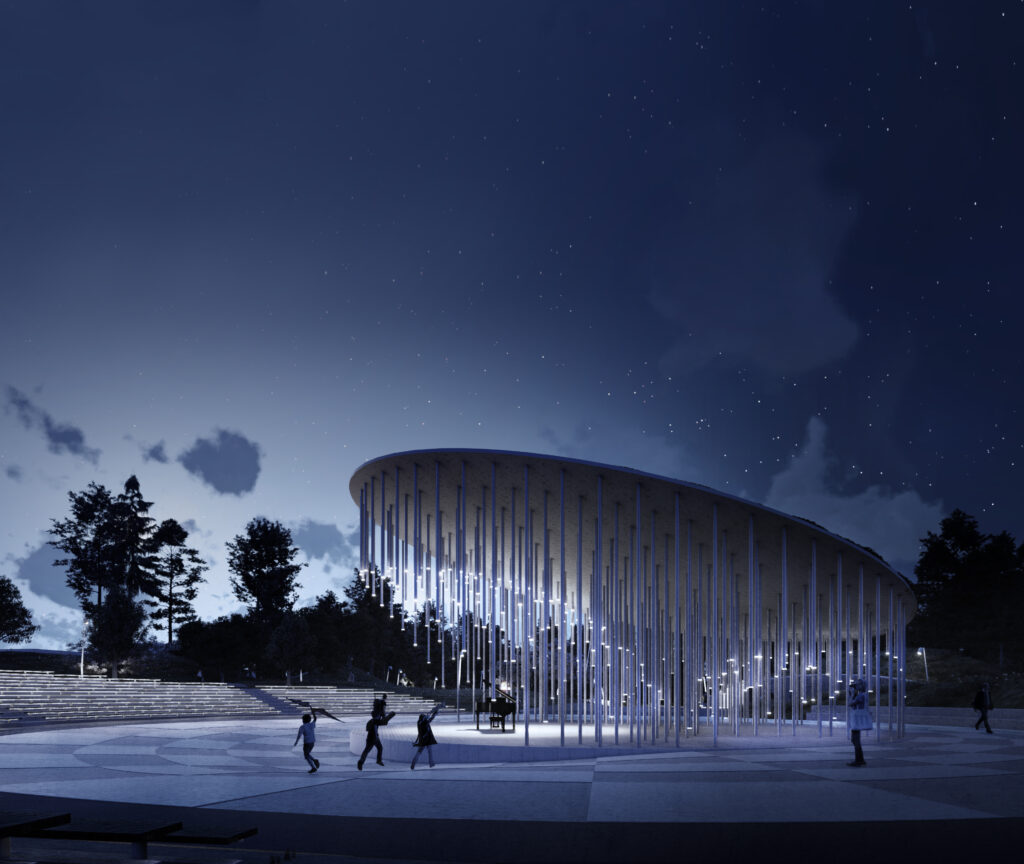

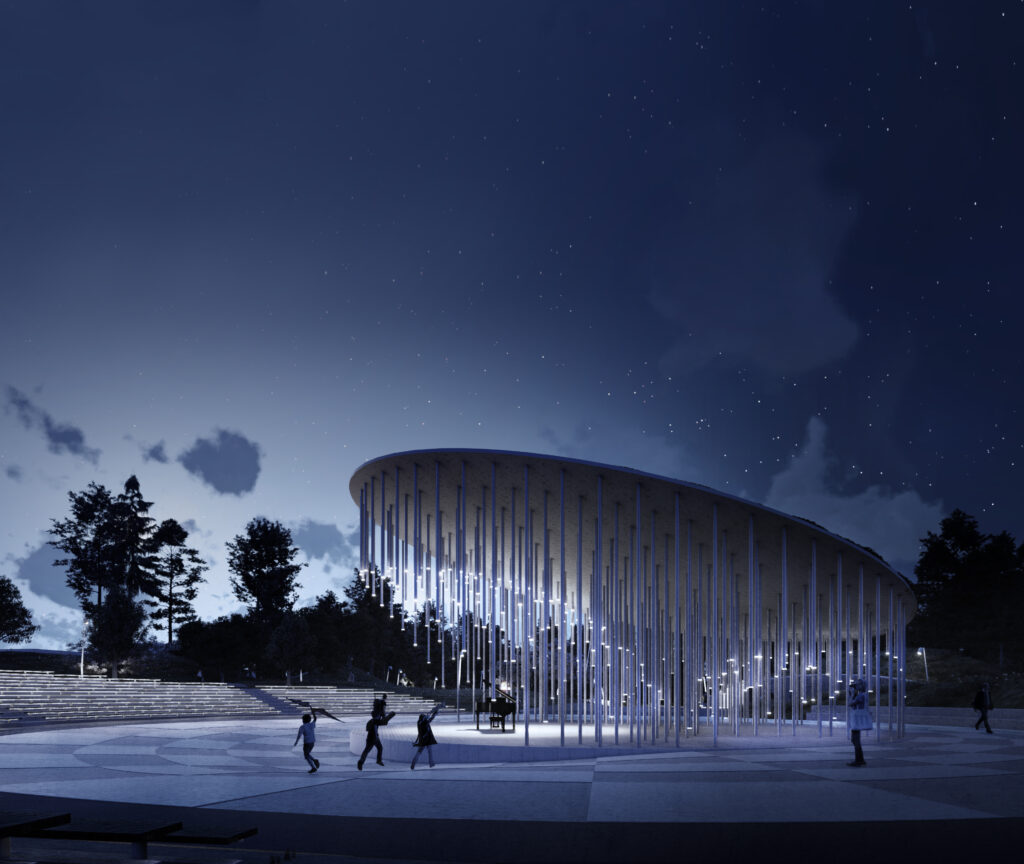

Excerpt from the winning entry “Kubu” in the architectural competition for the design of the Keila Song Festival Grounds and its outdoor space (2020). Molumba OÜ, Mareld OÜ. EAM Dk 1119

-

-

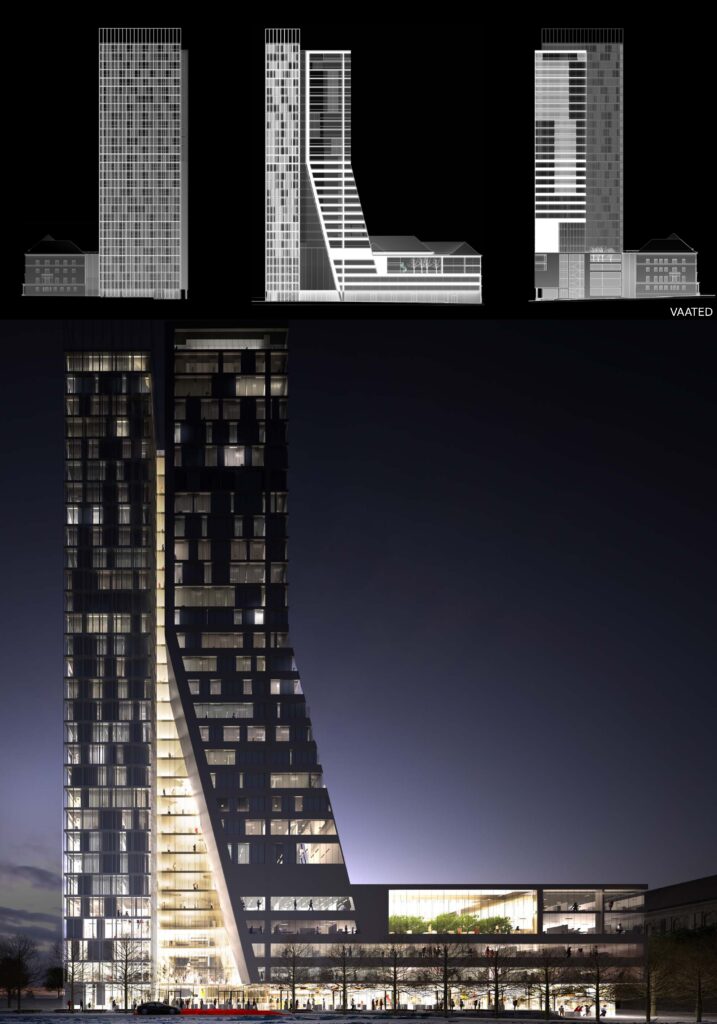

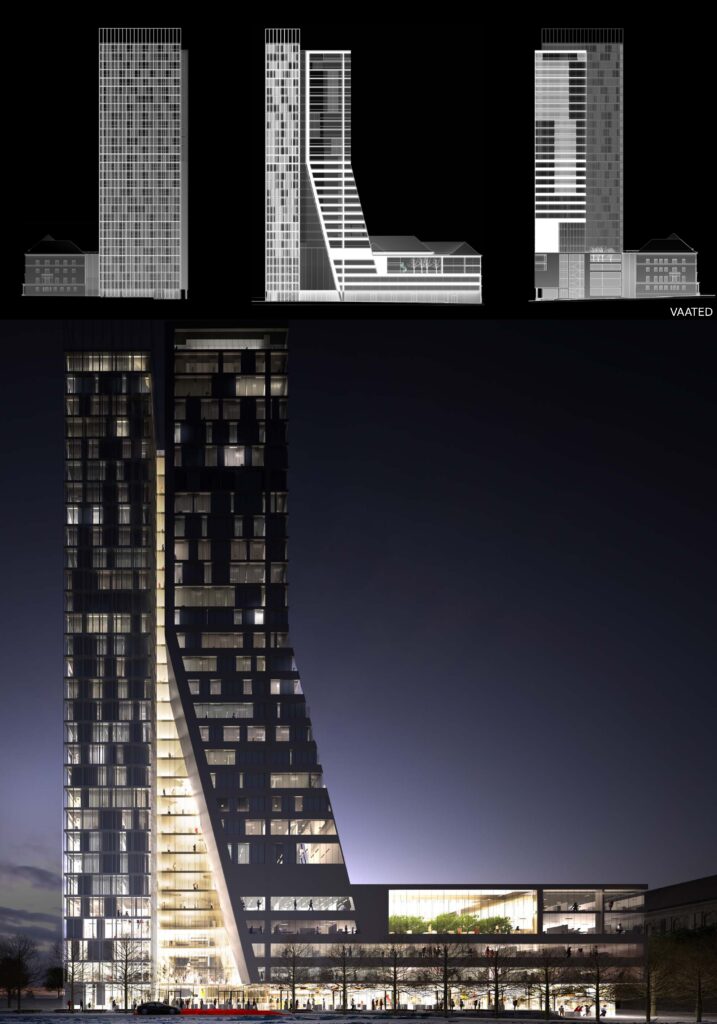

Elva Verevi Beach Building Architectural Competition (2023) entry “Lesila” (2nd prize). JVR arhitektuuribüroo. EAM Dk 968

-

-

Excerpt from the winning entry “Mätas” of the North Tallinn Model Kindergarten Design Competition (2022). Inphysica technologies OÜ and Kuu OÜ. EAM Dk 810

-

-

Excerpt from the EBS Campus Architecture Competition (2020) entry “Cremona” (2nd prize). Alver Architects. EAM Dk 823

-

-

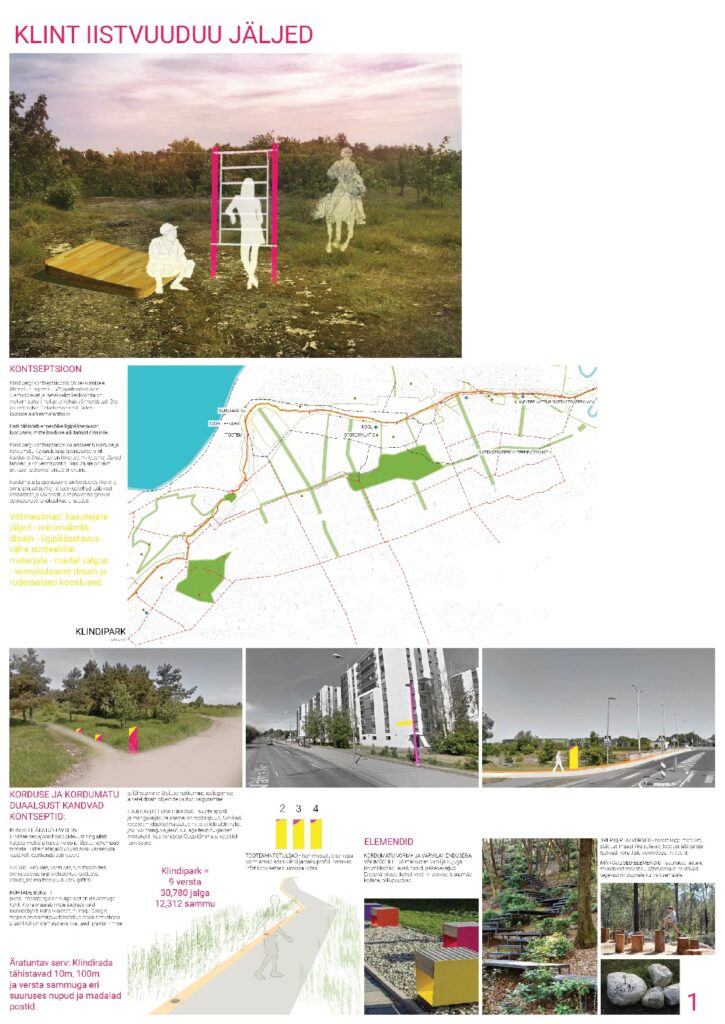

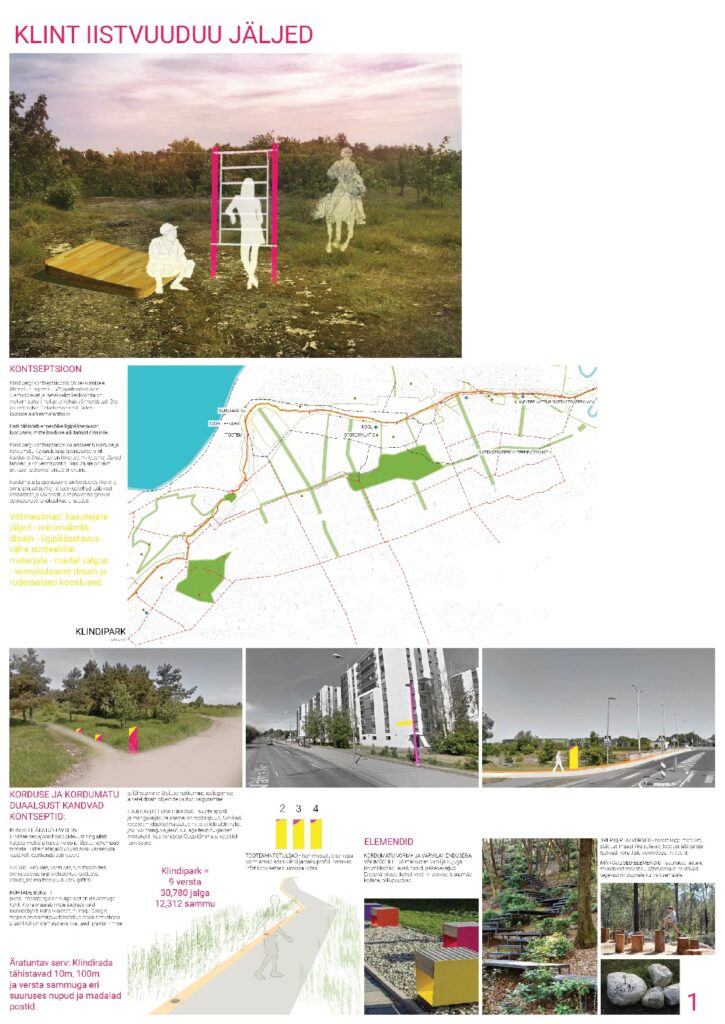

Excerpt from the Klindipark Landscape Architecture Competition (2022) entry “Klint Iistvuuduu jäljed” (3rd prize). Kino Maastikuarhitektid OÜ. EAM Dk 809

-

-

Excerpt from the entry work “Rebasesaba” (2nd prize) of the Maardu City Center Public Space Architecture Competition (2024). Studio TÄNA OÜ. EAM Dk 1048

Awarded works submitted to architectural competitions. EAM Dk 675 - Dk 1150

2020–2024 competition works in MEA collection

Estonia continues to hold many architectural competitions each year, around 30 of them public. It is a pleasure to look back and study the designs of buildings, landscapes and inventive interiors that have been recently completed or are about to be completed.

The museum’s digital collection was supplemented with works from public architectural competitions held between 2020 and 2024, which include not only the awarded works but also the commendations. The competition tasks and jury protocols are also invaluable for providing background information. Competitions have been organised all over Estonia, and among the objects there have been a relatively large number of competitions for squares, town centres and school buildings in the last five years. Beach houses and community centres also stand out. The high professional level of the competitions suggests that the most suitable solutions for their location have been found. Architects have given their competition entries very inventive keywords, but they love to give the names “Garden” and “Nest” in various forms.

In total, award-winning works from 117 architectural competitions (archive numbers DK 675 to DK 1150) were collected, recorded and supplemented with digital files. The works are visible in the Museum Information System in the digital collection of the Estonian Museum of Architecture, for example: Eesti muuseumide veebivärav – Audru keskväljaku arhitektuurivõistluse protokoll

The compilation was made possible with the help of the The Estonian Association of Architects, the Estonian Centre for Architecture, various local governments and the support of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia. Special thanks go to architect Kalle Komissarov, who did a thorough preliminary work compiling the competition information.

Text: Sandra Mälk

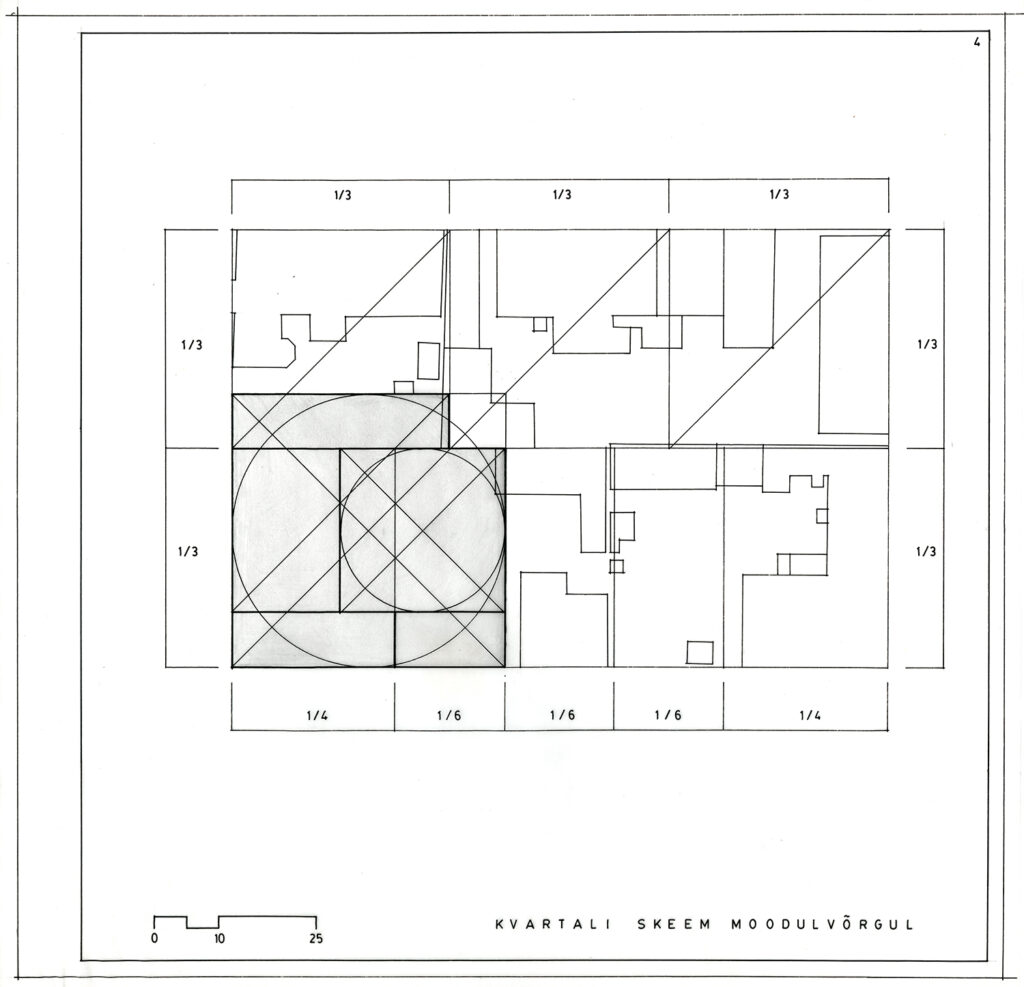

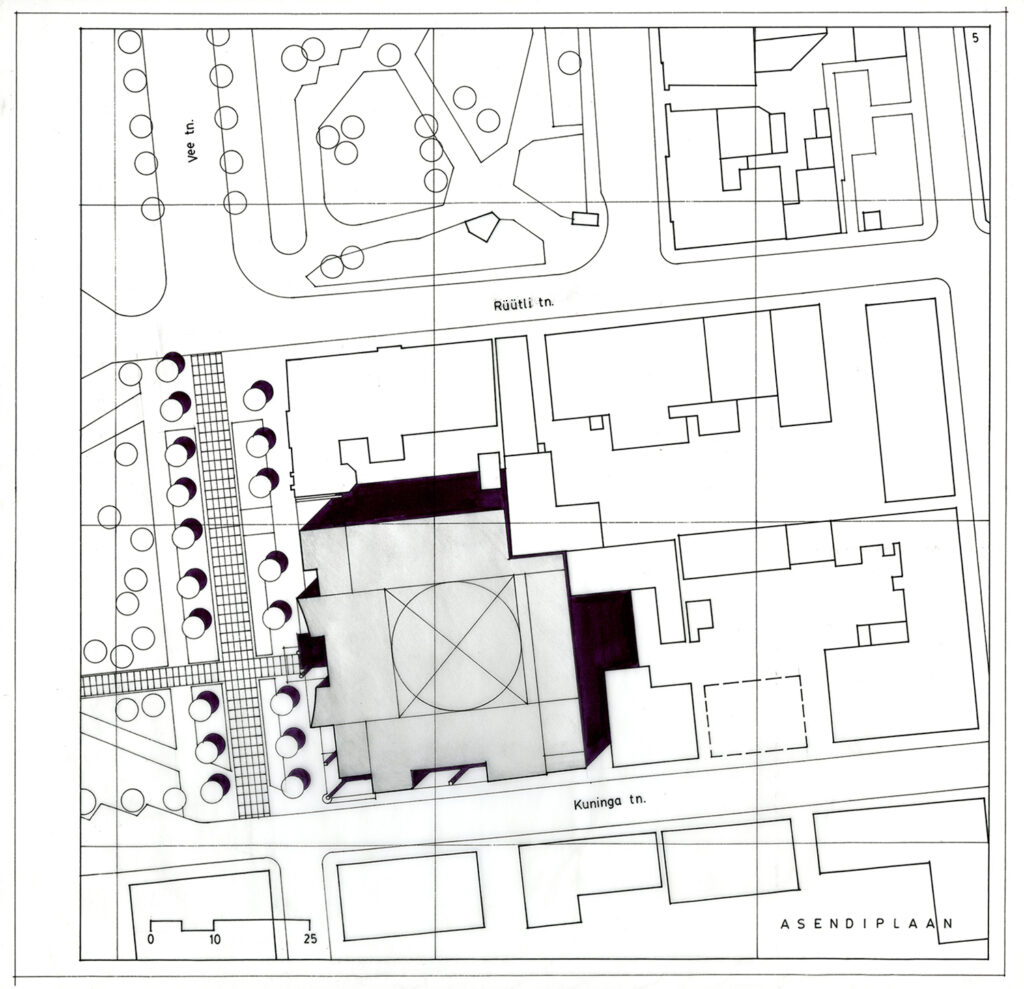

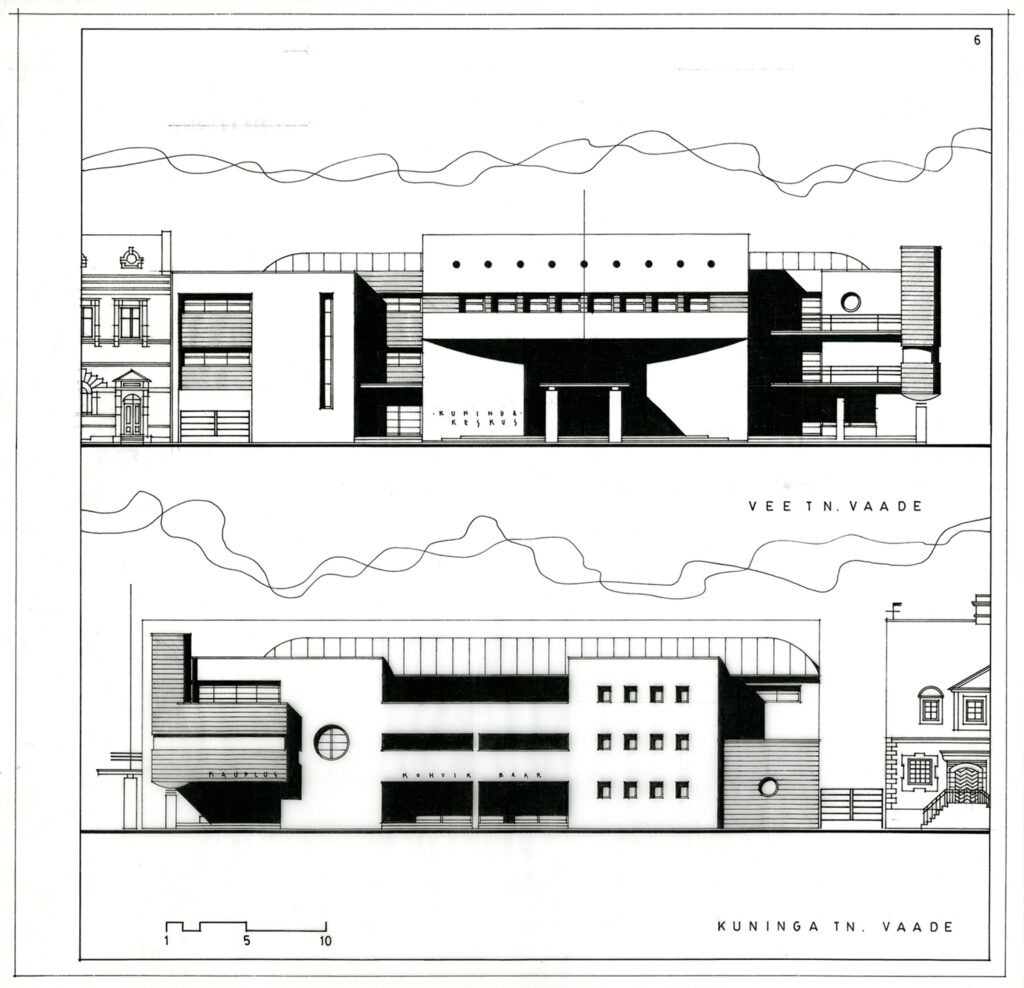

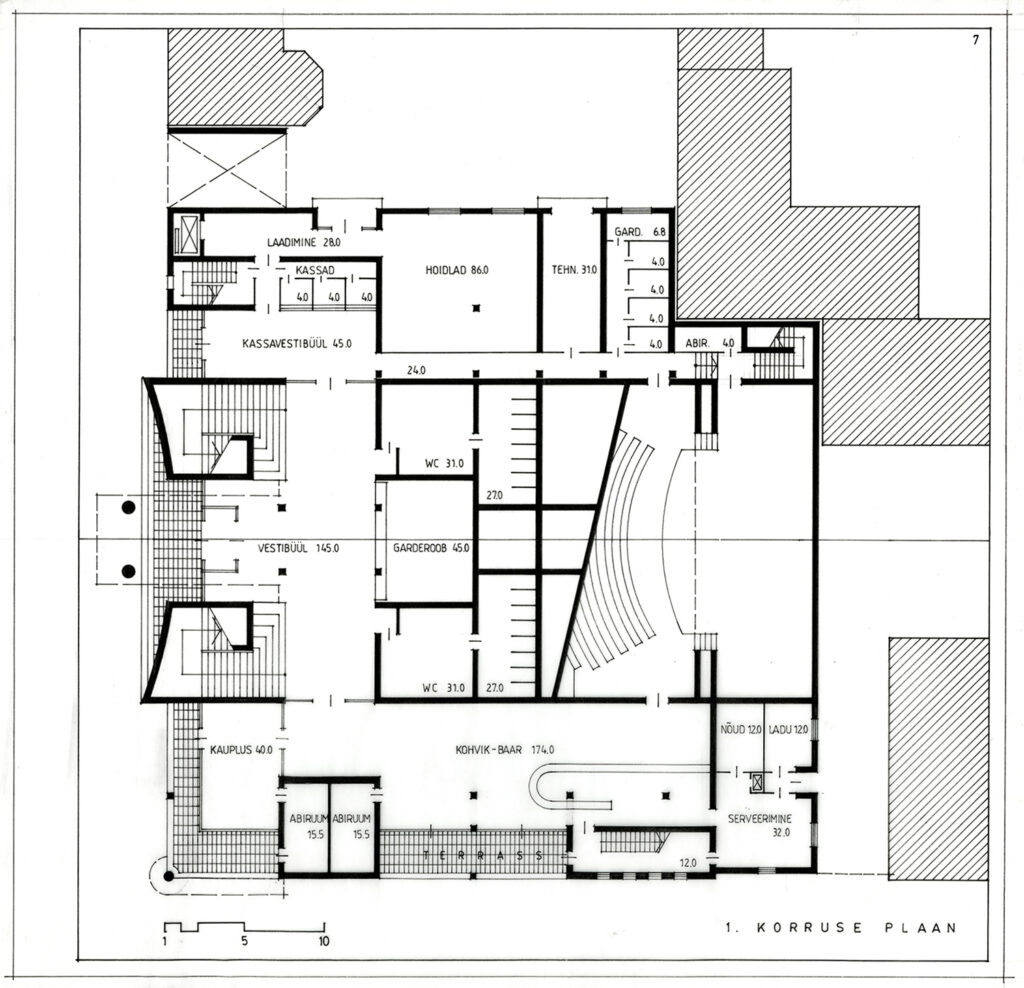

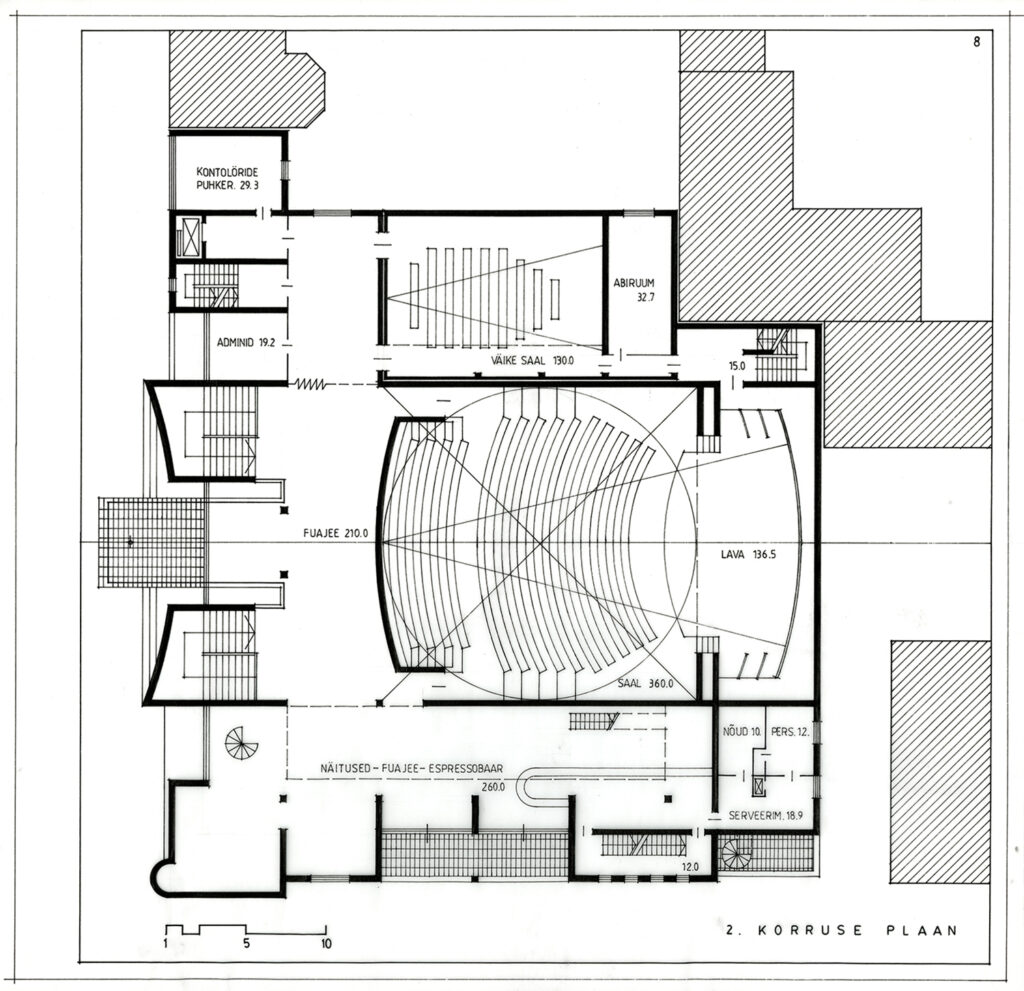

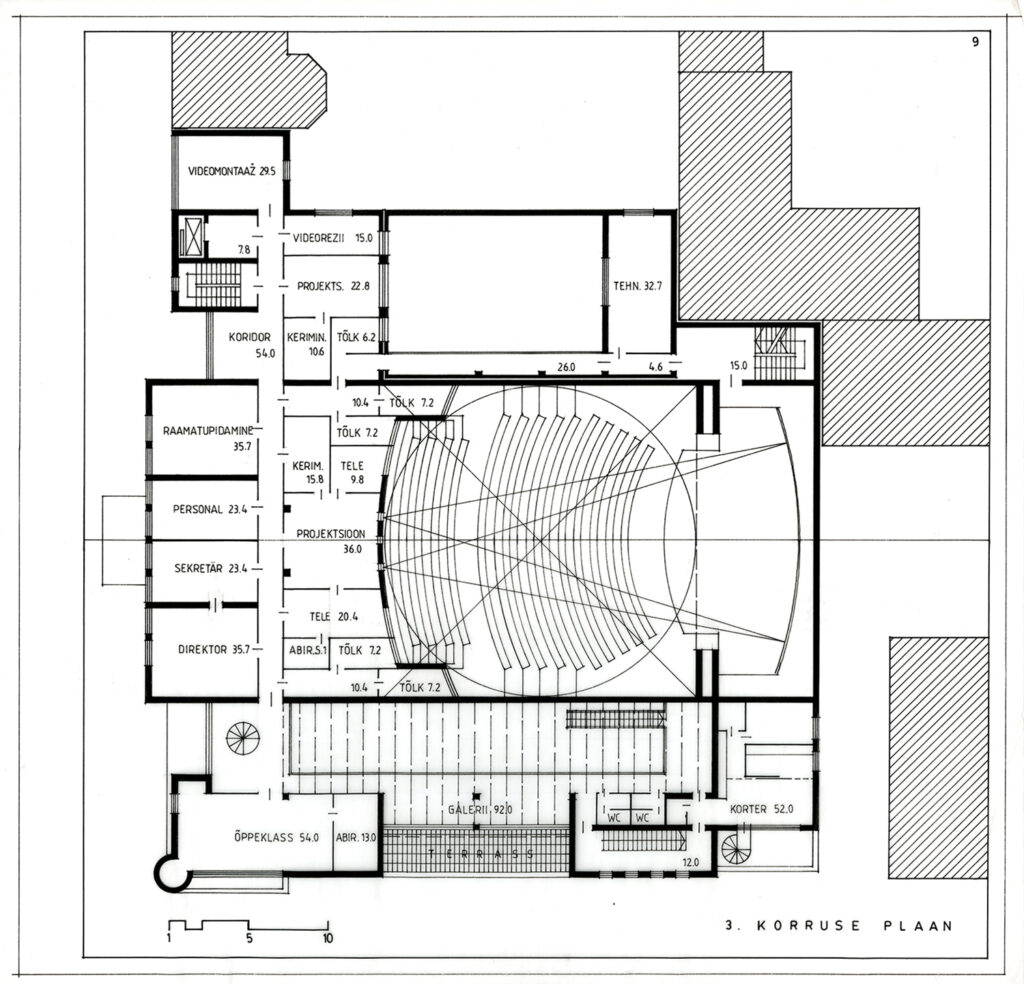

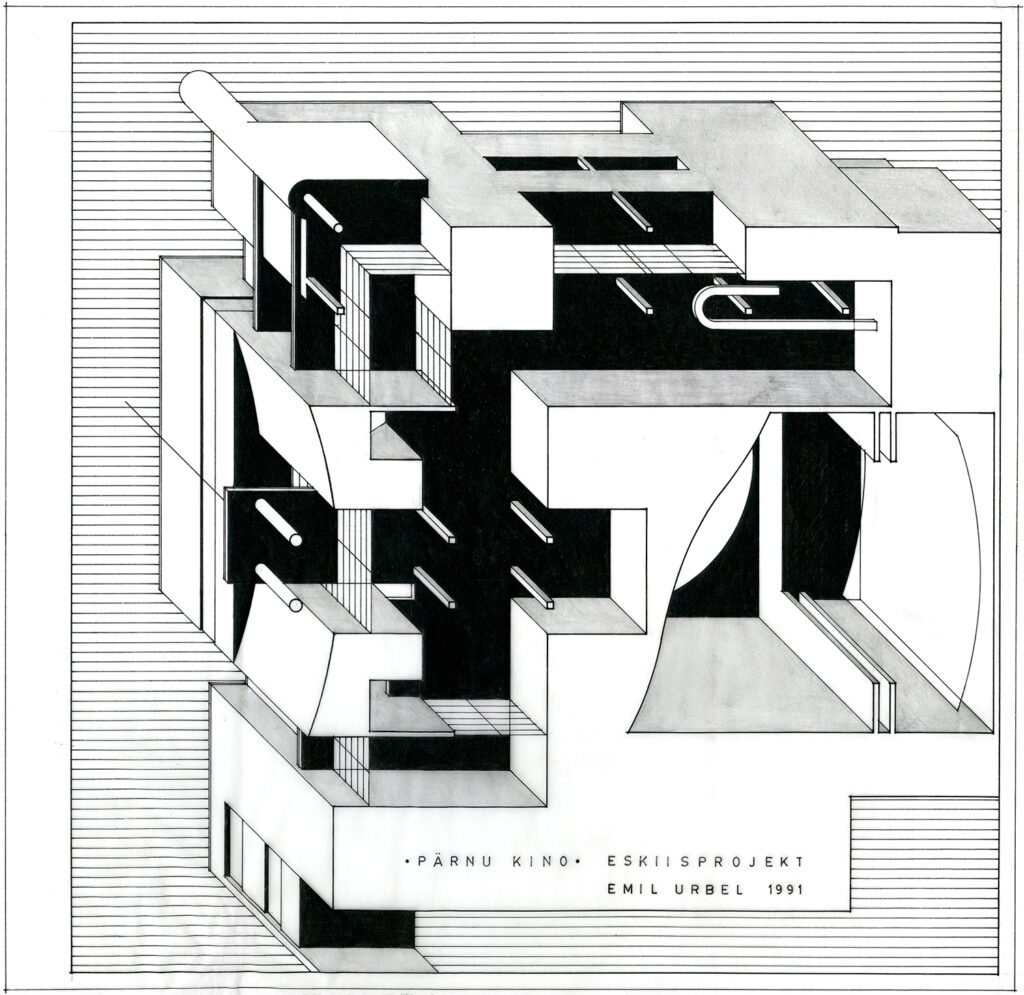

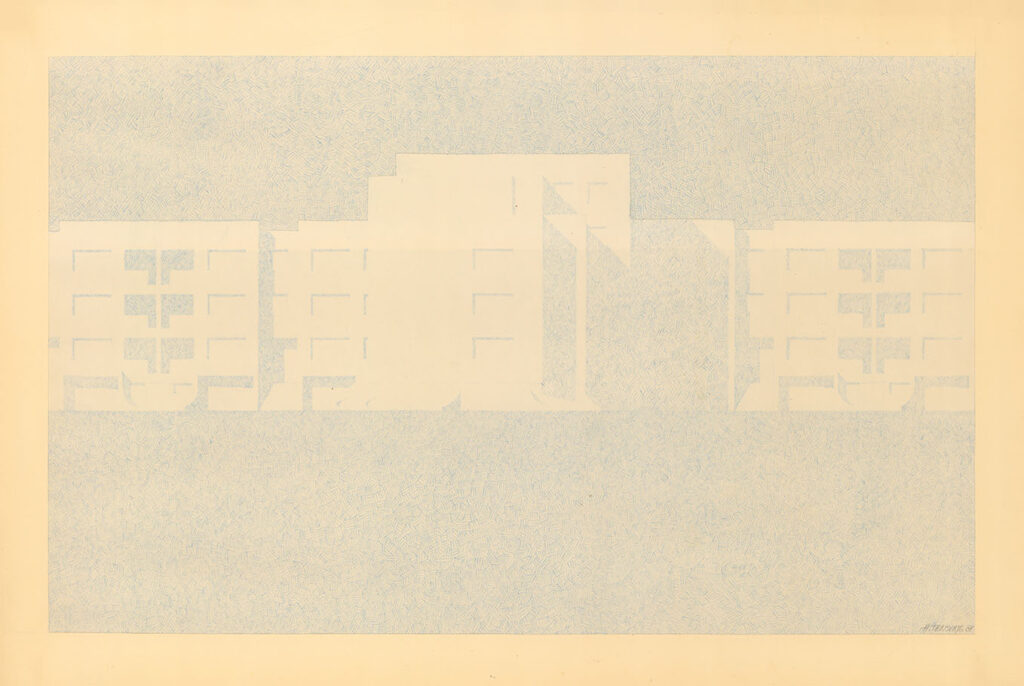

Emil Urbel, 1991. EAM 5.4.79

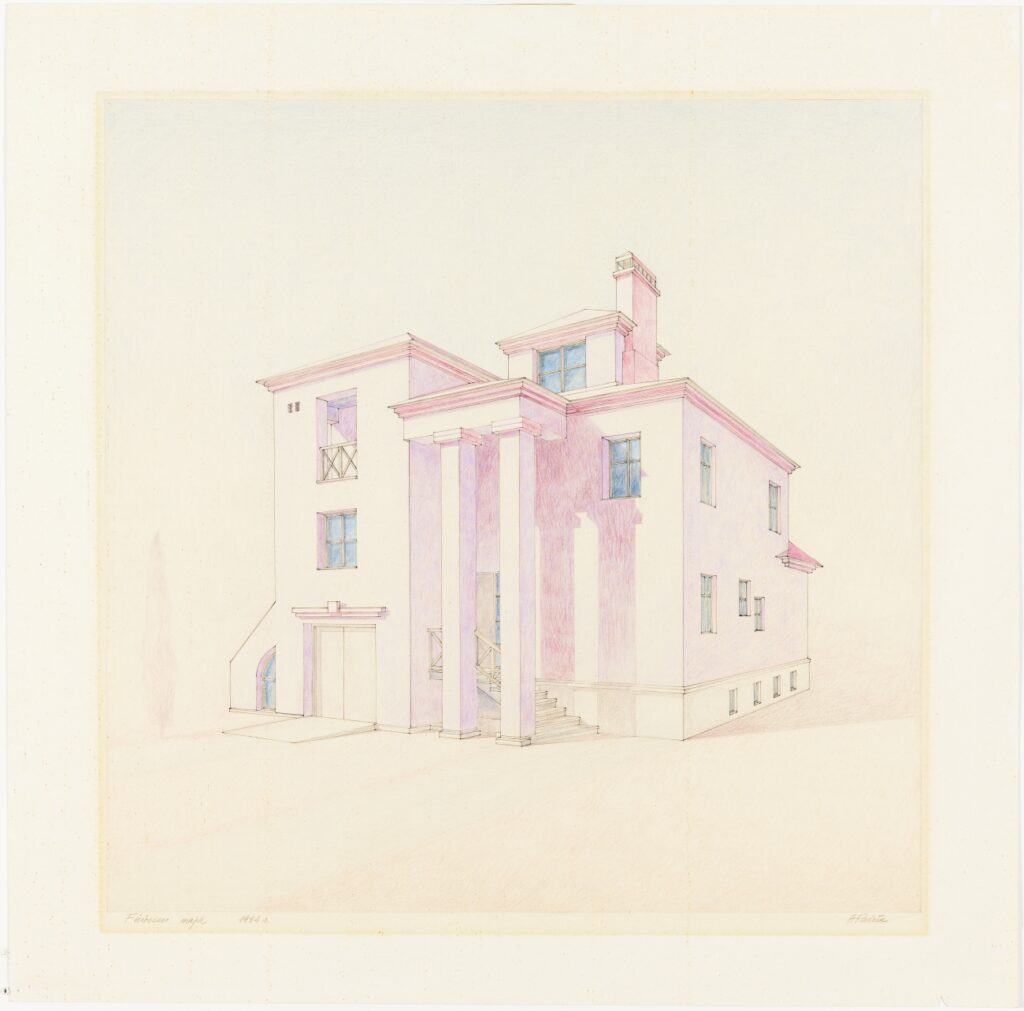

Pärnu cinema

The new cinema project in Pärnu is a fascinating example of architecture that was designed in the 1990s but never built. Designed by architect Emil Urbel, the cinema project entered into a dialogue with the city’s historical architectural tradition, using the modular land-use pattern of Pärnu’s city centre from the late 18th century as a basis for the layout of the neighbourhood and the design of the building. The new building was planned on the site of the Kiir cinema, which was to be demolished due to its obsolescence. The cinema building was to have two auditoriums, the larger with 420 seats and the smaller with 80 seats. Spacious corridors, a larger café and ancillary areas and a larger stage would allow the building to be used more flexibly for different types of events. On the third floor of the building, a housekeeper’s apartment with a separate entrance was planned, as well as a number of technical, office and ancillary rooms. The building was to be finished in white plaster and ceramic tiles, with the use of metal framing and steel detailing characteristic of the period. The area around the cinema on Vee Street was to be transformed into a spacious public space closed to traffic. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(To see more click on the image)

-

-

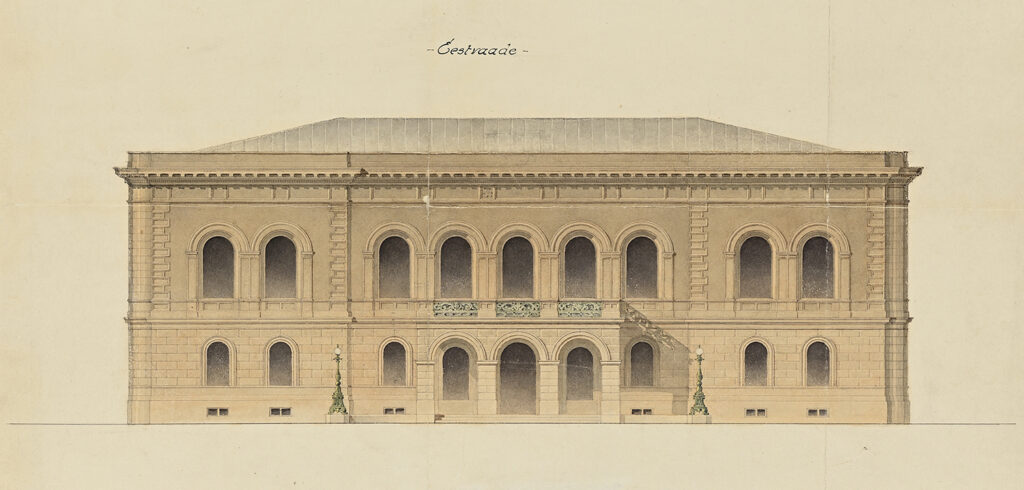

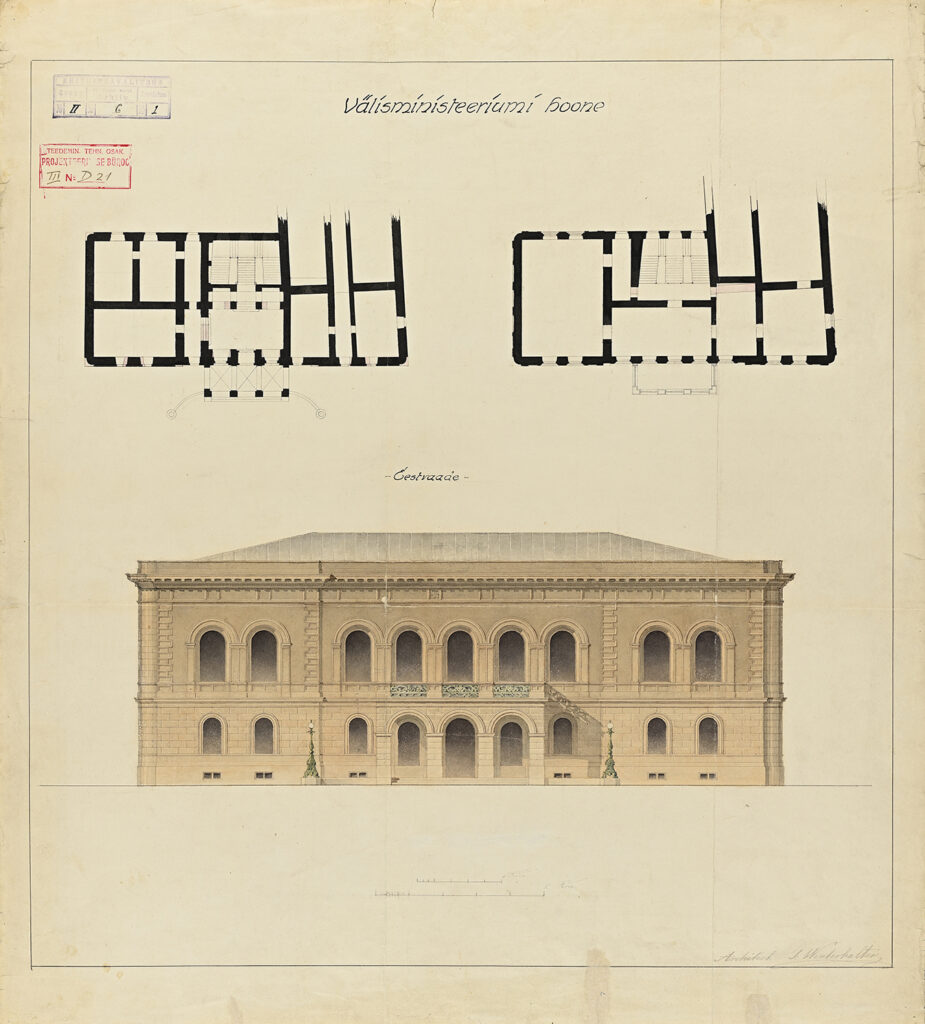

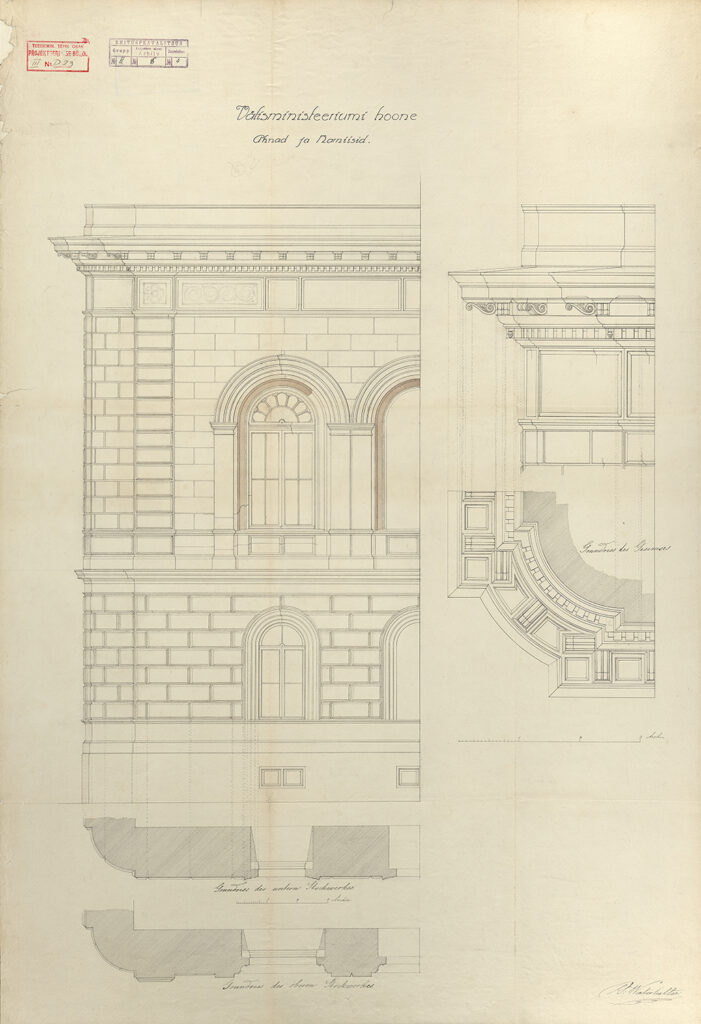

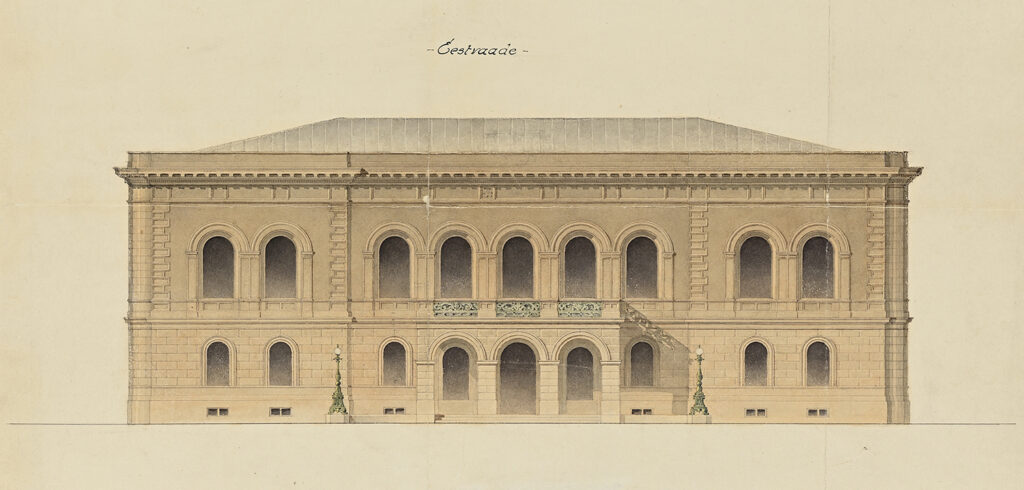

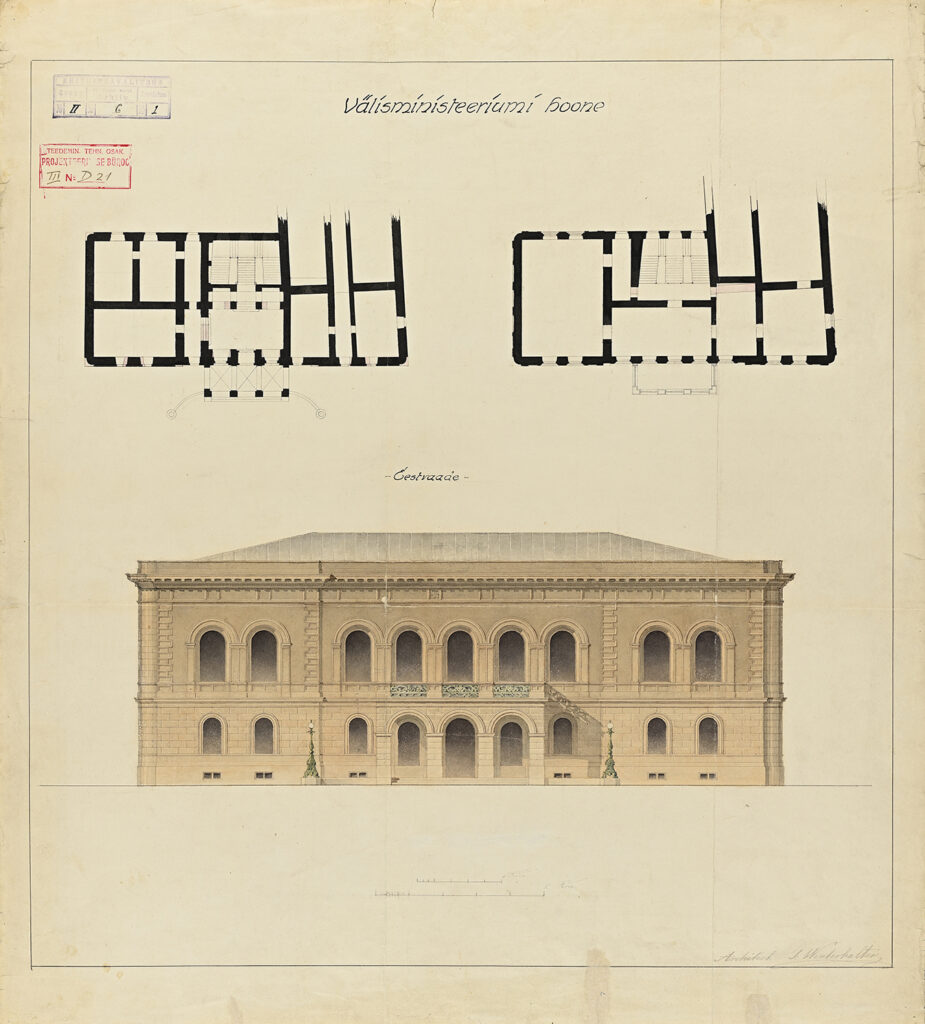

Estonian Knighthood House in Toompea, extract from the drawing

-

-

Estonian Knighthood House in Toompea

-

-

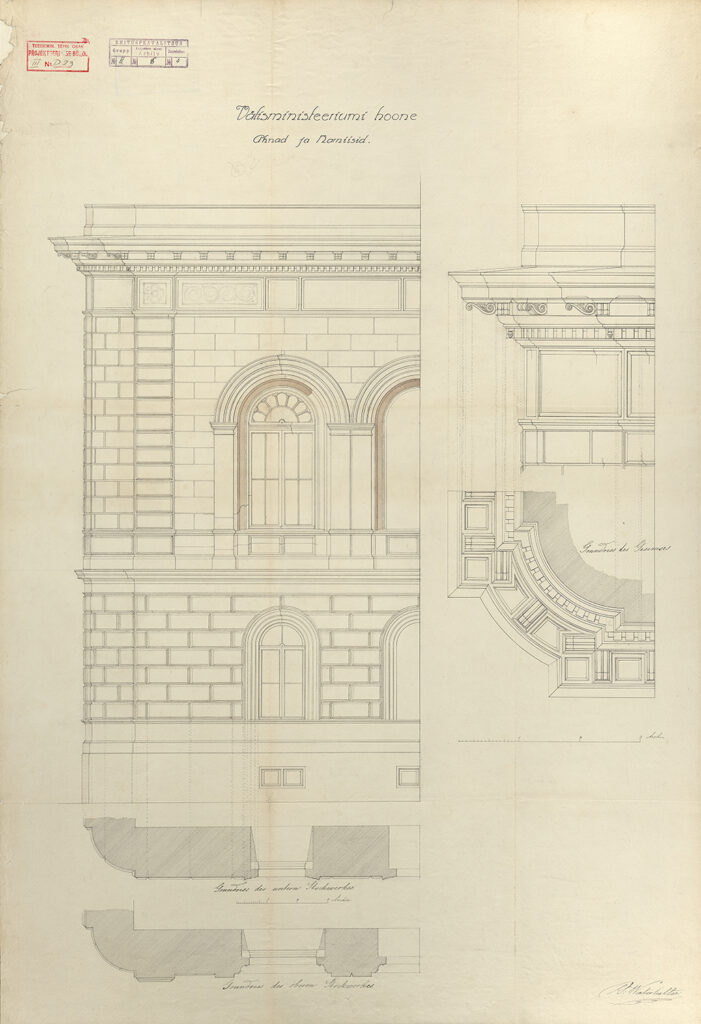

Detail of the façade of the Estonian Knighthood House

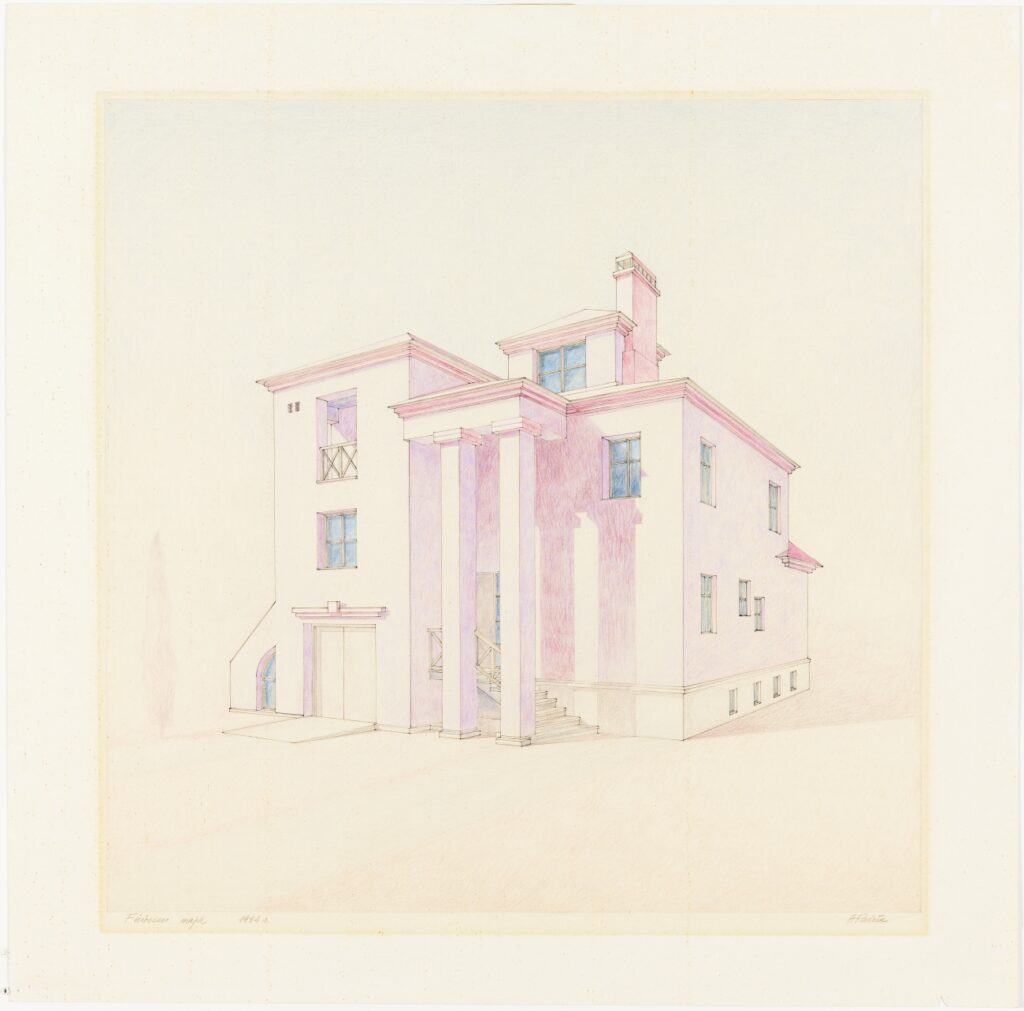

Georg Winterhalter, 1848. EAM 2.3.5

Estonian Knighthood House

The Estonian Knighthood House in Toompea was the only Neo-Renaissance building in Tallinn at the time of its construction. The building was originally designed by the architect of the Estonian Governorate, Christoph August Gabler, and construction began in 1845. However, Gabler’s classical architectural style did not meet the wishes of the knighthood. After a temporary pause in construction while the necessary building permits were obtained, and the completion of the major works in 1847, the Knighthood commissioned a new façade design from the young architect Georg Winterhalter from St Petersburg. The Neo-Renaissance façade is covered with a varied decoration. The walls are articulated by plasterwork and the windows are surrounded by a rich structural frame, the softness of the building’s rounded corners is counterbalanced by a heavy cantilevered cornice.

The Estonian Knighthood was abolished in 1920 and the building became the property of the state. The building has housed the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1920-1940), the National Library of Estonia (1948-1992), the Art Museum of Estonia (1993-?) and the Estonian Academy of Arts (2009-2016).

Drawings of the façade of the Estonian Knighthood House are among the oldest in the museum’s collection. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(To see more click on the image)

-

-

That Blue Rain. Anli Tensing, 1984.

Anli Tensing, 1984. EAM 5.9.2

That Blue Rain

The delicate minimalist drawing was completed for the architectural exhibition at the Tallinn Matkamaja (hiking house, currently named as Hopner House) in 1985. The work was awarded the prize of the ESSR Ministry of Culture for “poeticised depiction of new districts”. The exhibition itself was a landmark of its time. For the first time, architects were able to show their free creative work alongside their building projects and planning schemes in a exhibition – they could submit architectural drawings, fantasy projects, graphics, models, architectural designs (see Arhitektuurikroonika ’85. Tallinn “Valgus” 1987). Several works from the exhibition at the time belong to the museum’s collection, as well the exhibition’s guest book. Anli Tensing’s (Tummi, 1957-2006) prize-winning work, together with a few dozen other works, unfortunately ended up in an attic of an Old Town building, where it was found in 2022. Text: Anne Lass

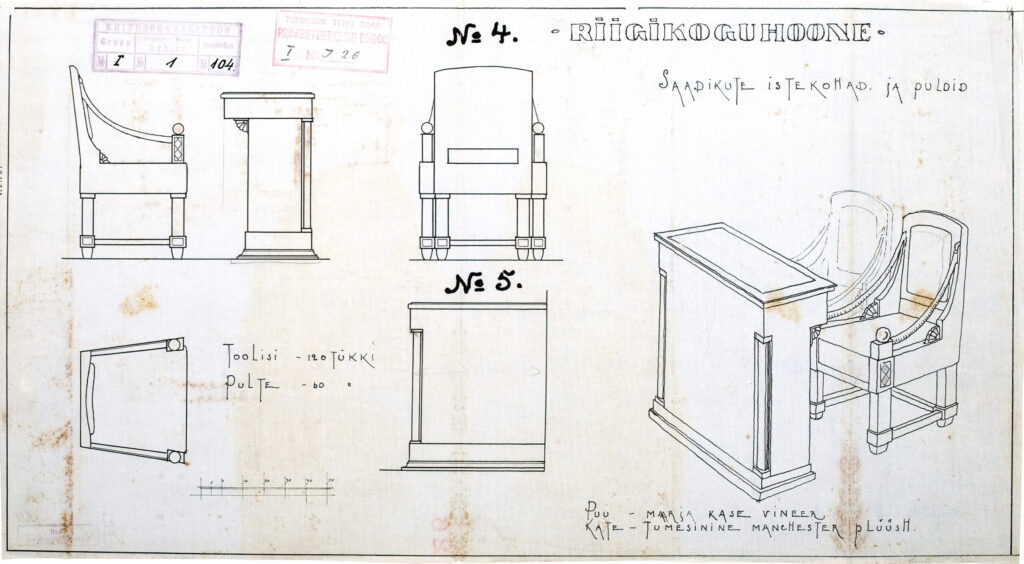

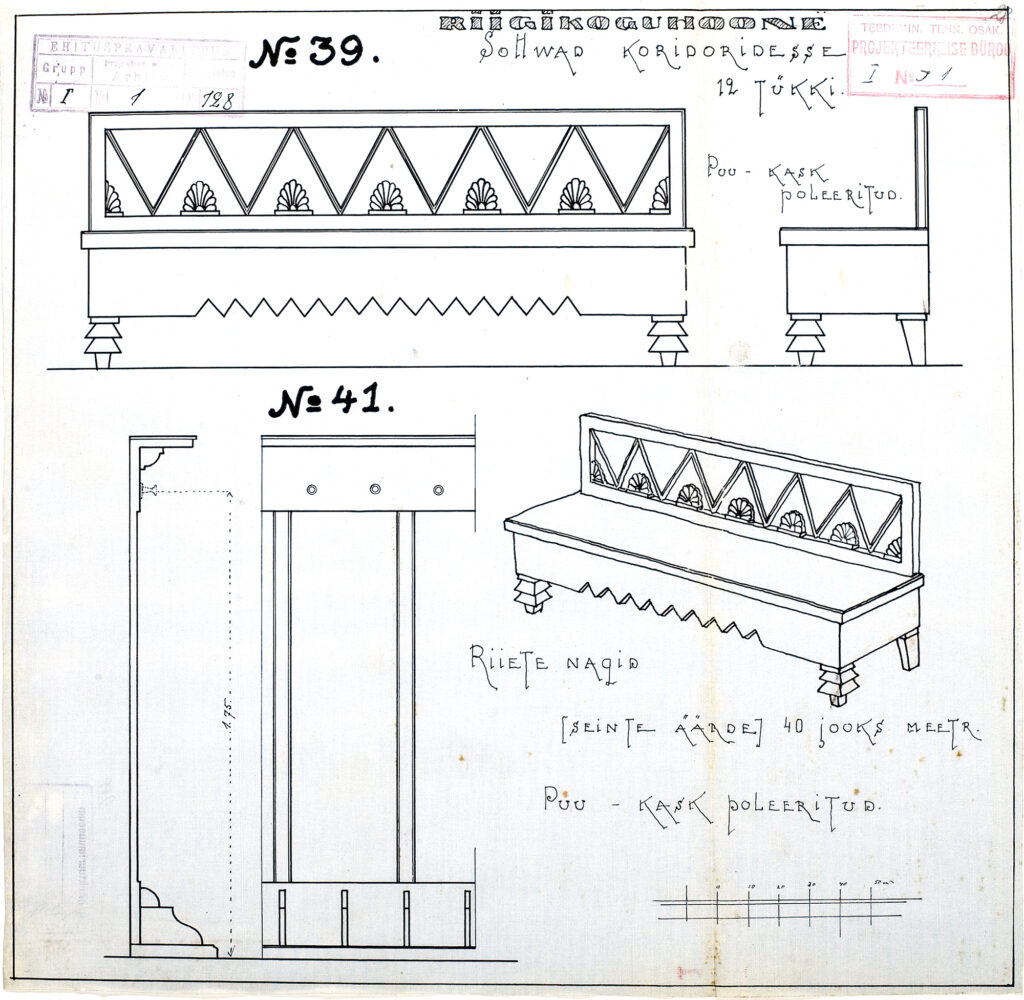

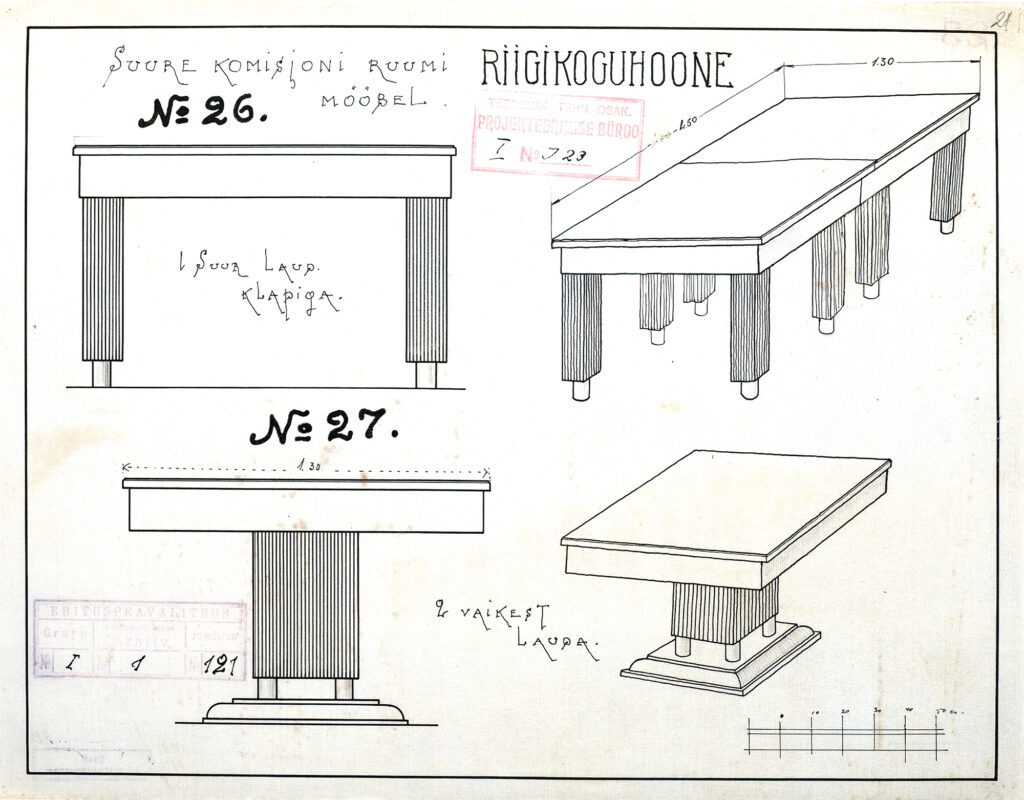

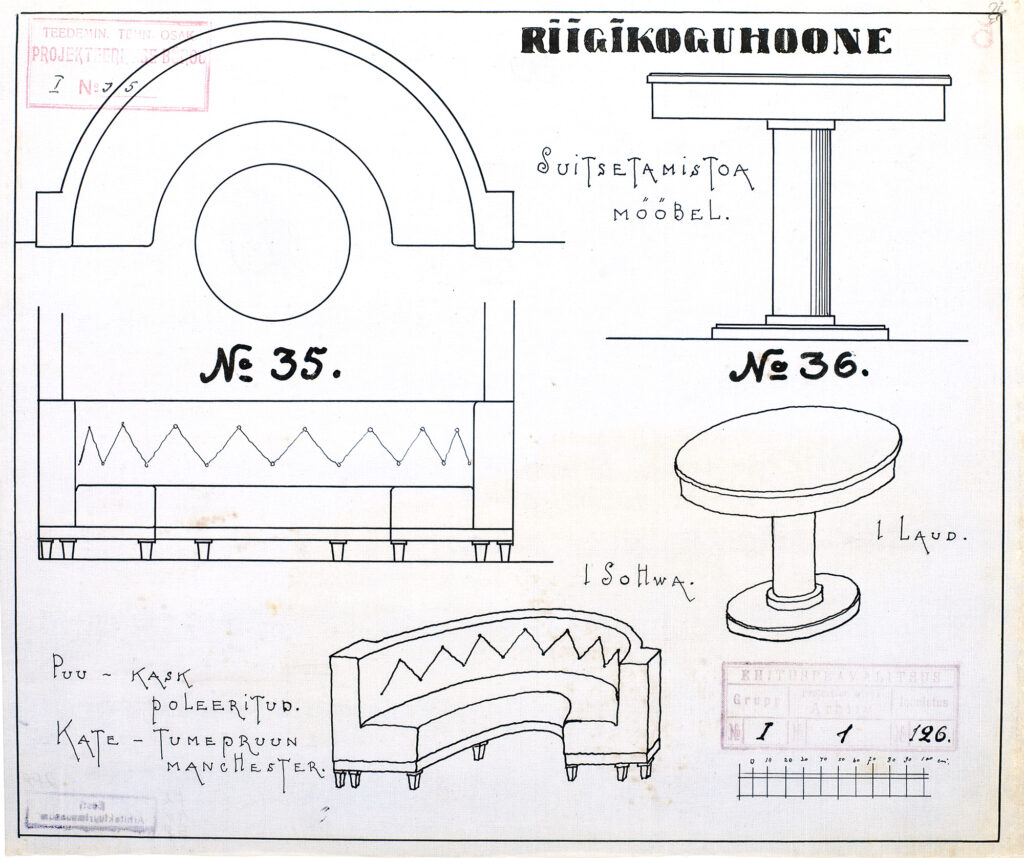

Herbert Johanson, 1920-1922. EAM 2.11.8

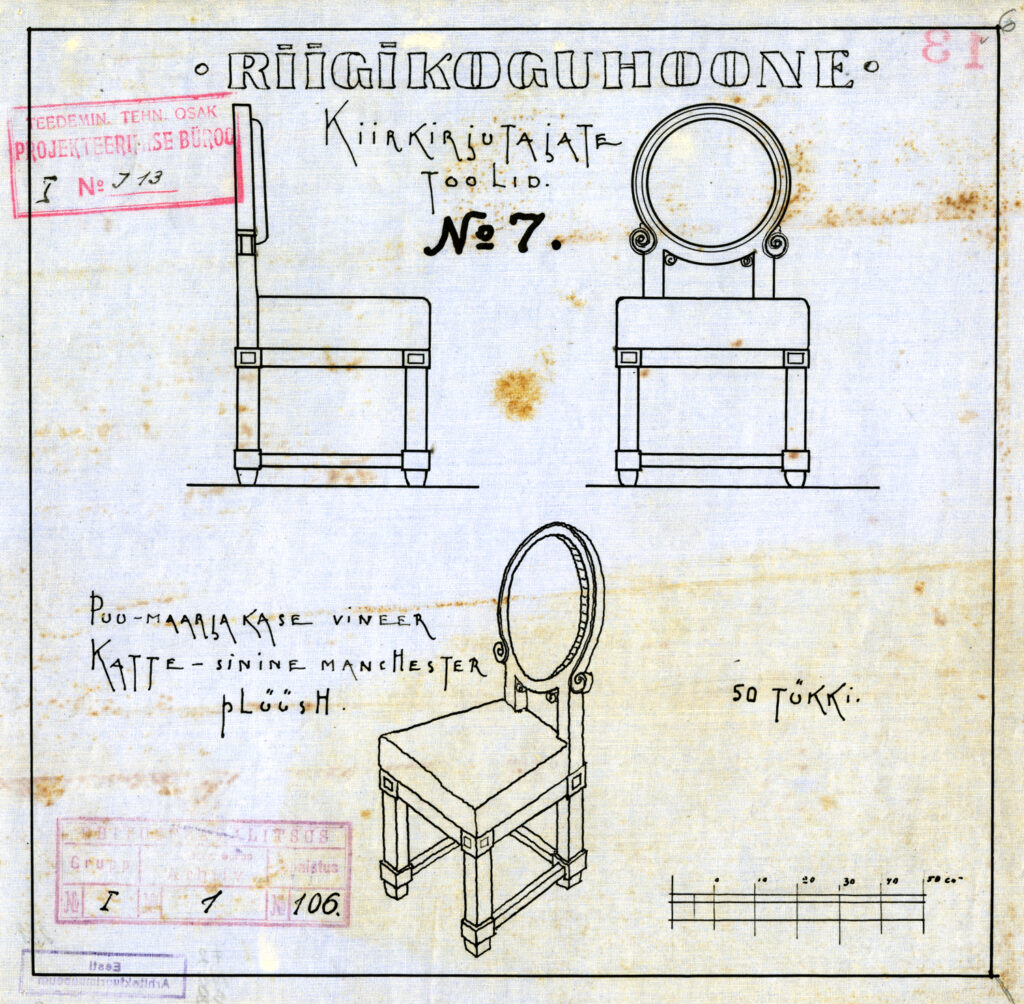

The furniture designs of the Parliament building

In 1922, the most important state building of the newly independent Republic of Estonia – the new modern Parliament building (architects Herbert Johanson, Eugen Habermann 1920-1922) – is completed in Toompea. “It is a simple, yet self-conscious and distinctive building, which gracefully combines the individual sense of design of the authors and the fit with its medieval surroundings, while remaining modern.” This is how art critic Hanno Kompus characterised the Parliament building in his introduction to the book “20 Years of Building in Estonia: 1918-1938 “. Herbert Johanson’s designs were also used to create the unique furniture of the Parliament building, which repeats the geometric shapes of the building’s interiors and the Art Deco zigzag motif. The furniture was produced by the Luther factory, for whom it was the first major public commission (see Jüri Kermik. A. M. Luther 1877-1940. Innovation of form from material. Tallinn, 2002). The high quality of Lutermas’ work is demonstrated by the fact that most of the 100-year-old furniture is still in use today.

The museum has more than 30 furniture designs for the Parliament building, ranging from the podium in the sitting room to the coat racks. The original drawings come from the archives of the former Ministry of Roads and were transferred to the museum in 1992. Text: Anne Lass

(klick on the picture to see more)

-

-

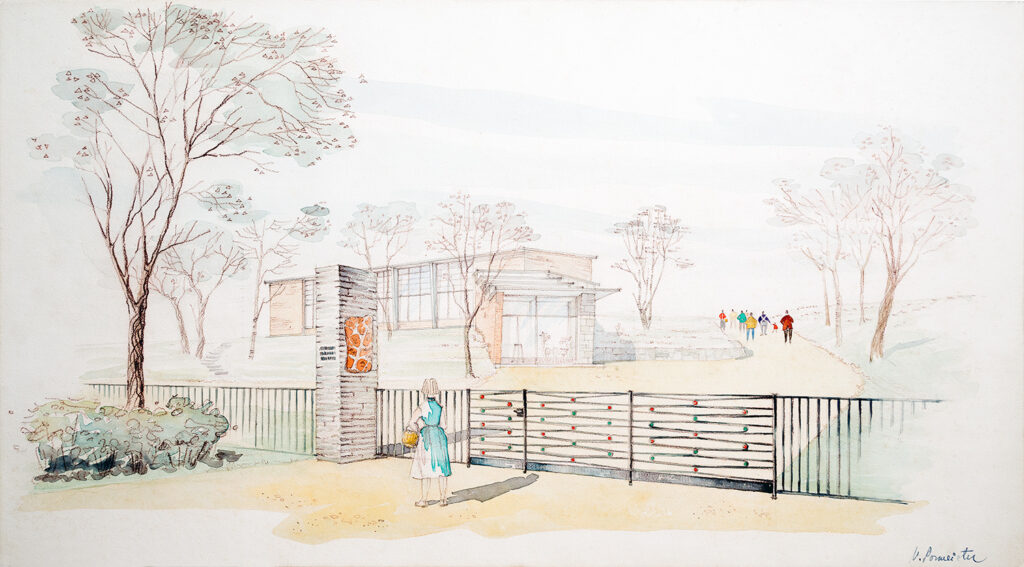

House for a Romantic. Ain Padrik

-

-

House for a Physicist. Ain Padrik

Ain Padrik, 1983, 1984. EAM 55.1.3 ja 55.1.4

House for a Romantic – House for a Physicist

At the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, architecture and especially residential building was starting to look at historical examples, and a relationship with the client or with the location of the building was deemed to be important. Designing a house provided a chance to experiment with the limits of freedom of expression and set an intriguing assignment to interpret the client through architecture. The romantic’s house followed the example of the Arts and Crafts movement in 19th-century England. This movement cherished handicraft and often employed motifs from medieval architecture: romantic towers and complex roof landscapes. The physicist’s house with its more clearly defined volumes proceeds from the wishes of the client. The physicist did not ask for large windows, preferring a lot of wall space and dimly lit interior. A thorough working project was also finished in addition to this sensitive perspective view. Construction received a building permit, but the physicist’s house was never completed. Ain Padrik donated the drawings to the museum in 2016. Text: Sandra Mälk

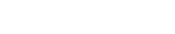

Valve Pormeister, design 1958, completed 1960. MEA 33.1.22

Flower Pavilion at Pirita Road in Tallinn

Architect Valve Pormeister, who graduated university in garden- and park design, claimed that nature was an intrinsic component of her, which was why she often put landscape first in her works. The Flower Pavilion melts into the landscape with a sensitivity characteristic of the architect’s signature. In addition to organic architecture, the building, which step-by-step ascends a hillside, also represents Finnish-influenced cornice architecture. This approach was rare and reviving (i.e. Nordic) in Soviet Estonian society at the time, as the rigidity of the early 1950s still echoed. The detail-rich interior sketches demonstrate the architect’s great enthusiasm for designing flower exhibitions – an activity she also practiced afterward. Text: Sandra Mälk