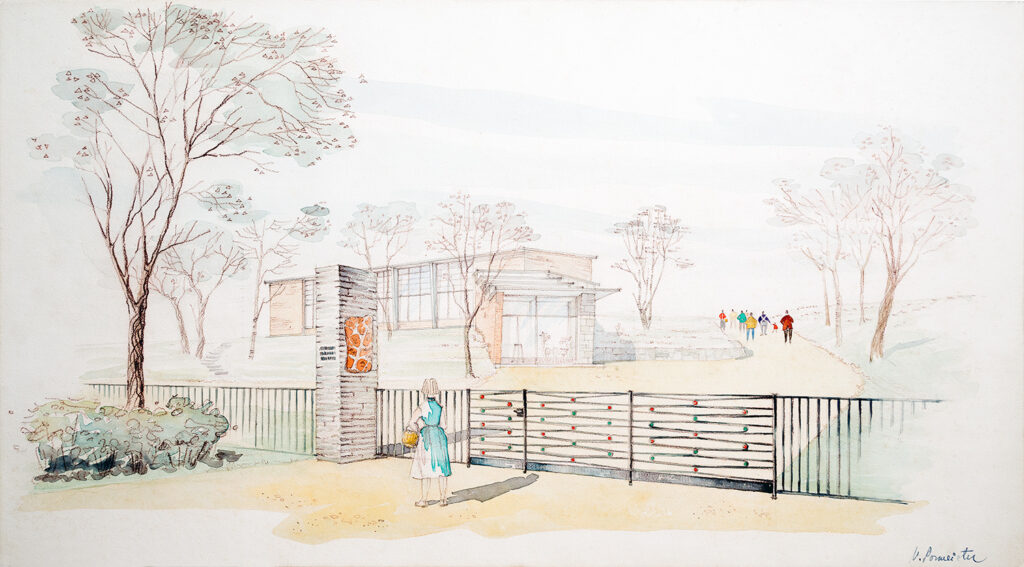

Valve Pormeister, design 1958, completed 1960. MEA 33.1.22

Flower Pavilion at Pirita Road in Tallinn

Architect Valve Pormeister, who graduated university in garden- and park design, claimed that nature was an intrinsic component of her, which was why she often put landscape first in her works. The Flower Pavilion melts into the landscape with a sensitivity characteristic of the architect’s signature. In addition to organic architecture, the building, which step-by-step ascends a hillside, also represents Finnish-influenced cornice architecture. This approach was rare and reviving (i.e. Nordic) in Soviet Estonian society at the time, as the rigidity of the early 1950s still echoed. The detail-rich interior sketches demonstrate the architect’s great enthusiasm for designing flower exhibitions – an activity she also practiced afterward. Text: Sandra Mälk

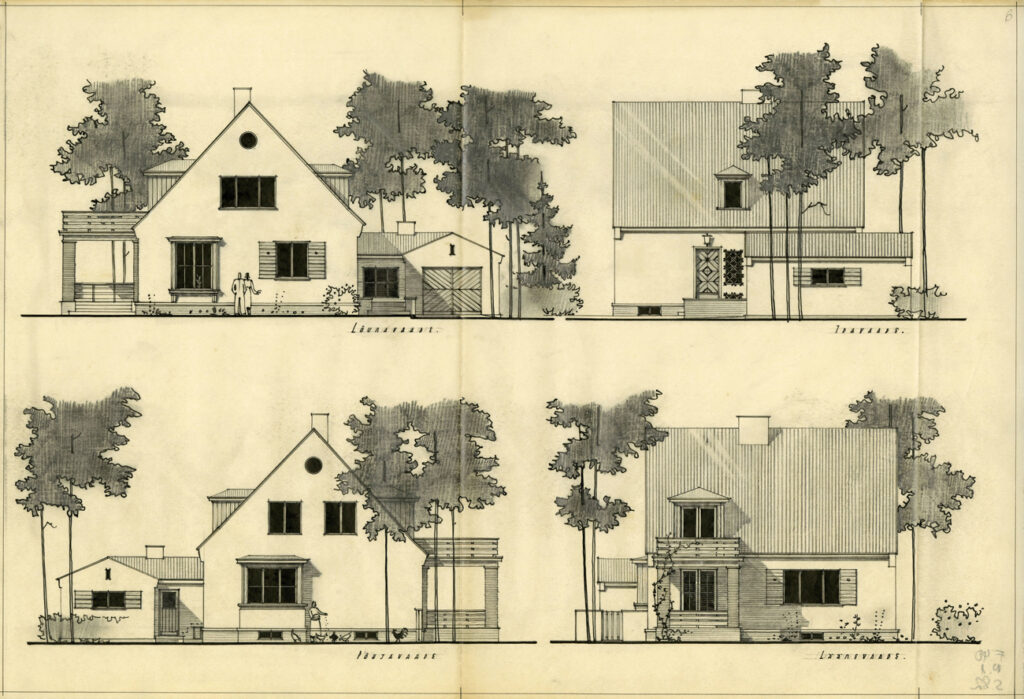

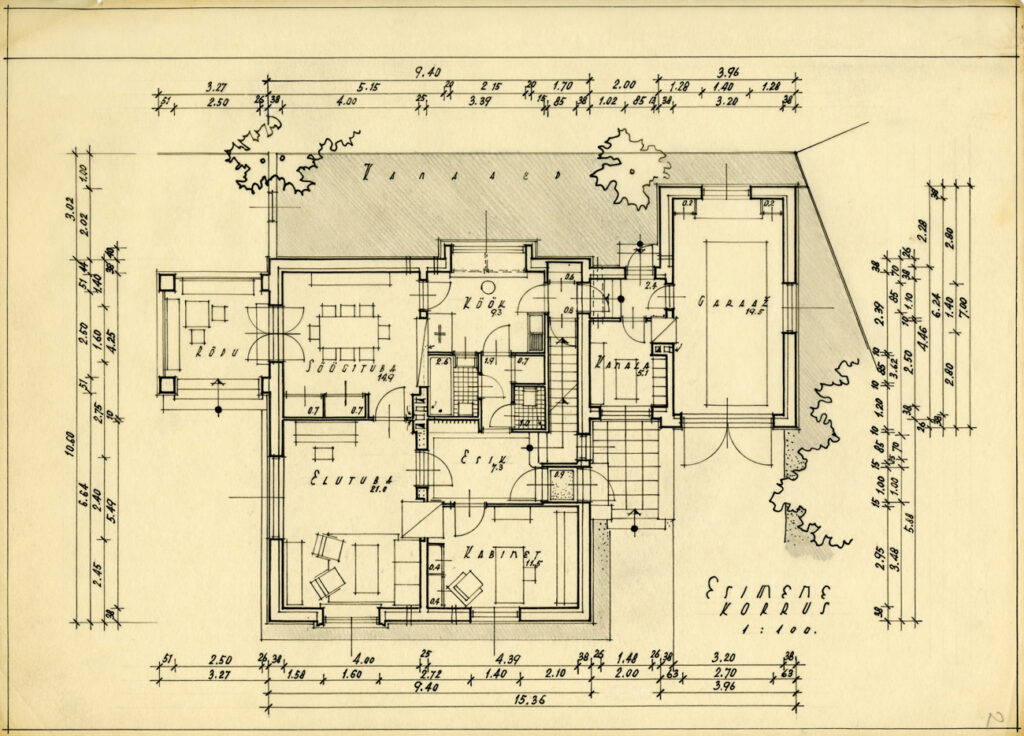

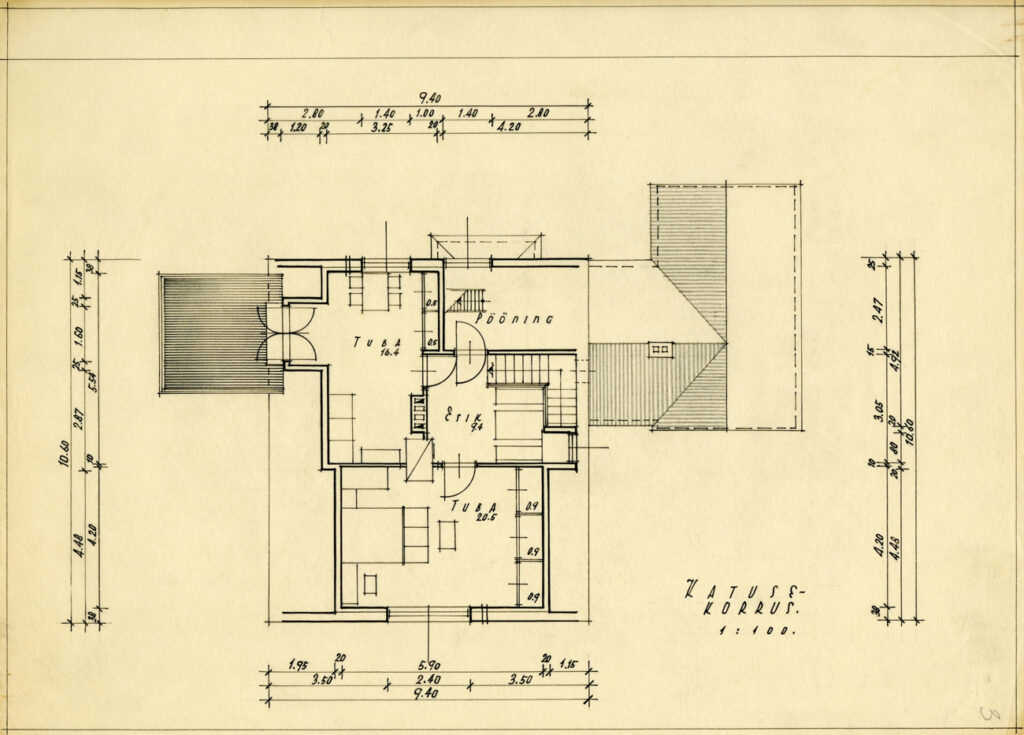

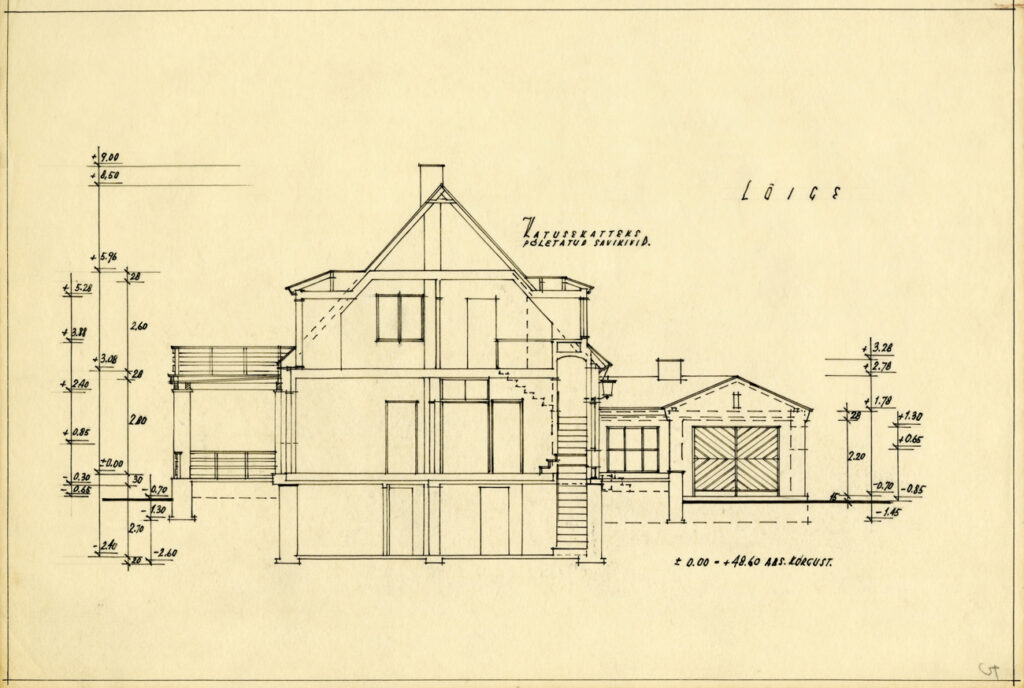

Edgar Velbri, design 1932, constructed. MEA 14.1.46

Johannes Orro’s dwelling at Raudtee Street in Tallinn

Bustling Nõmme had already grown from a holiday village to a reasonably-sized town (possessing town privileges from 1926–1940, after which it became a district of Tallinn) when café-owner Major Johannes Orro presented the design for his new building to the town government in 1932. True to the era of thriving small businesses, the ground floor of the residential building in the Kivimäe neighbourhood housed a bakery – an unquestionably successful venture, given its close proximity to the railway station. The design was drafted by young architect and Tallinn Technical University student Edgar Velbri, who was fascinated by old-fashioned architecture; probably a result of his summer internships at the Estonian National Museum, during which he surveyed Estonian farm structures. The hipped roofs, romantic shutters, and vertical siding characteristic of Estonian agricultural architecture later carried over into the architect’s personal style. Complementing such features with his talent for creating functional floorplan solutions, Velbri gained great public favour and demand, and his cosy structures gained their own nickname: “Velbri houses”. This single-page ink drawing on tracing paper is a typical 1930s residential design project, which was submitted for official approval along with an explanatory letter. Text: Sandra Mälk

Tiit Kaljundi, architectural competition 1975, perspective drawing 1984, unrealised. MEA K-53

Dr Spock’s residence

Tiit Kaljundi’s relationship with Soviet Estonia’s official architectural scene was conflicted, as one may have expected from an avant-garde artist. The ruling power saw monotonous mass apartment blocks as a simple opportunity to ease the deficit of dwelling-spaces. For Kaljundi, however, it was a situation that dampened creativity and encouraged a superficial attitude towards the residential environment, to which he responded with a starkly opposite project – the post-modernist villa. The design, which was originally entered in the magazine Japan Architect’s “House for a Superstar” competition in 1975, was dedicated to famous American doctor Benjamin Spock, whose childrearing book was widely read in Estonia at the time. This version was drafted for an exhibition highlighting the “Tallinn School” of architects, which was held in Finland in 1984. Kaljundi’s protest against the Soviet Union’s rigid, anonymous building culture is obvious. By creating an analogy between construction-stages and life-stages, he clearly expresses the opinion that man and architecture are not separable. The house and the concrete-sidewalked property around it symbolised the various stages of life. Kaljundi’s drawing presents the structure from an axonometric perspective, which enables its imagination in a three-dimensional scale on a two-dimensional surface. Text: Sandra Mälk

Mart Port, ca 1968. MEA 52.2.12

Sketches of Tallinn’s Väike-Õismäe residential neighbourhood

When designing the Väike-Õismäe residential neighbourhood, Mart Port and Malle Meelak – a shining tandem of Soviet-Estonian urban planning – seized the opportunity to shape it into an ideal city and avoid mistakes that commonly accompanied the construction of high-density housing projects. In the centre of the district designed for 40,000 residents, they placed an artificial lake with developments extending radially from it centre point. The drafts vividly convey Port’s genuine fascination with the concept of a ring-city. Compared with the earlier Mustamäe district, which was constructed as several independent micro-districts, Väike-Õismäe’s solution was unique and even so novel that there were numerous bumps along the road to gaining approval for its design. The architects had been expected to produce ordinary designs for an urban network, which would contain several smaller neighbourhoods and linear streets. This was precisely what Port and Meelak wished to avoid, instead producing a concentric street-plan with spacious outdoor areas that allowed for a more human dimension. Text: Sandra Mälk

Pirita beach pavilion, photographer Rein Vainküla

Pirita beach pavilion

Photographer Rein Vainküla of State Design Office Tsentrosojuzprojekt has captured the photogenic central element of the Pirita beach pavilion with its dining establishments, in which the combination of architectural parts provides an impressive melange. The shot, built on contrasting tones and diagonal lines, creates a somewhat deceptive, even constructivist impression. A human scale is added to the photograph by the beach-goers that seem to be almost strategically positioned.

Planning the new Pirita beach pavilion was instigated for the sailing regatta that took place in Tallinn as part of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. To make way for the new building, which was completed in 1979, a wooden beach pavilion designed by Edgar Kuusik and Franz de Vries and built in 1929, was demolished. At first, the new building, blindingly light and bright in the sun, had a restaurant, bar, cafeteria, three banquet halls, and in each wing rooms intended for beach-goers. The building was designed by Mai Roosna at Tsentrosojuzprojekt. At the beginning of the 2000s, the building was almost completely rebuilt to house apartments (architect Ülo Peil). Text: Jarmo Kauge

Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ in Narva, aerial photographer Endel Grensmann

Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ in Narva

Harsh reality: The Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ in Narva designed by Paul Alisch in 1896 is the only neo-Byzantine religious building in Estonia – here seen in its Soviet context of dishonour. Before the war, the grand building stood in the now non-existent district of Joaoru in line with Alexander’s Cathedral creating an impressive architectural ensemble. Kiriku tänav (Church Street), which once connected the two churches, was however, filled with apartment blocks after the war. The 2002 photograph by aerial photographer Endel Grensmann was purchased by the museum for its collection in 2003. Text: Jarmo Kauge

Peeter Tarvas, 1950s. MEA 40.1.82

Dwelling of family Kangur

There is a recognisable style to the dwellings erected in Estonia’s immediate post-war years. These stone buildings with tall gabled roofs and raised gutter-lines can be found all across the country. Their construction derives from traditional German heimat architecture, intended to give residents a cosy sense of home with the help of small elements such as romantic shutters. The style also pleased the Stalinist regime: it was sufficiently unlike the dominant pre-war flat-roofed structures, which carried “unfit” Western European values. The project was donated to the museum by Maria Tarvas along with many materials from the family collection in 2006.