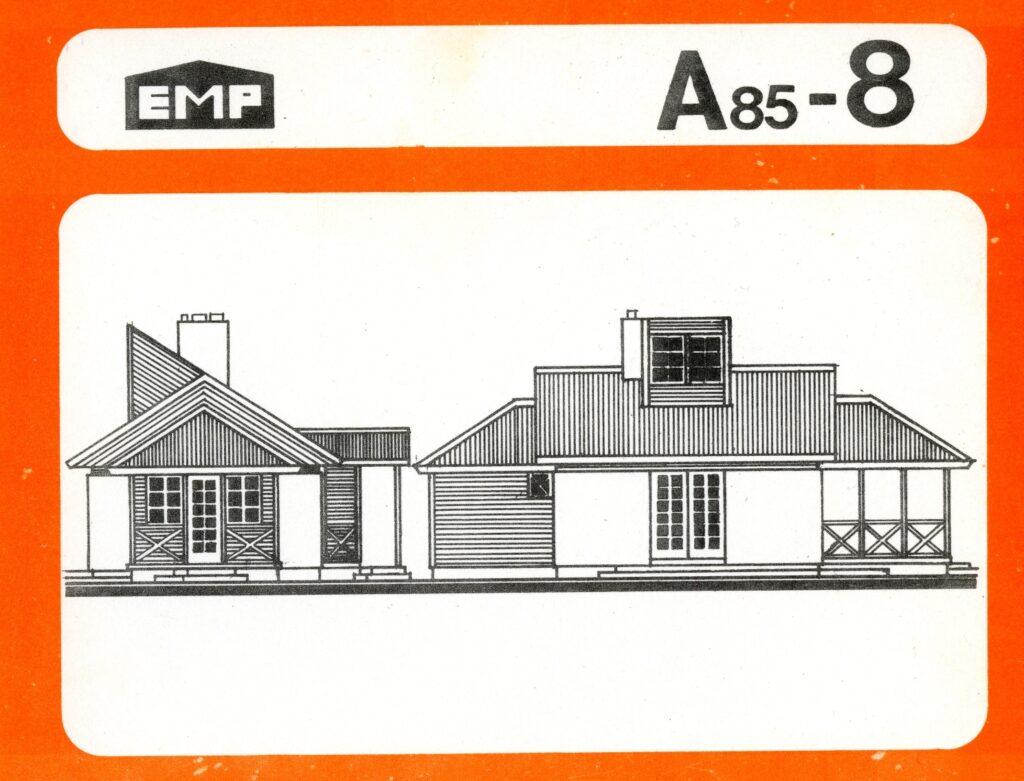

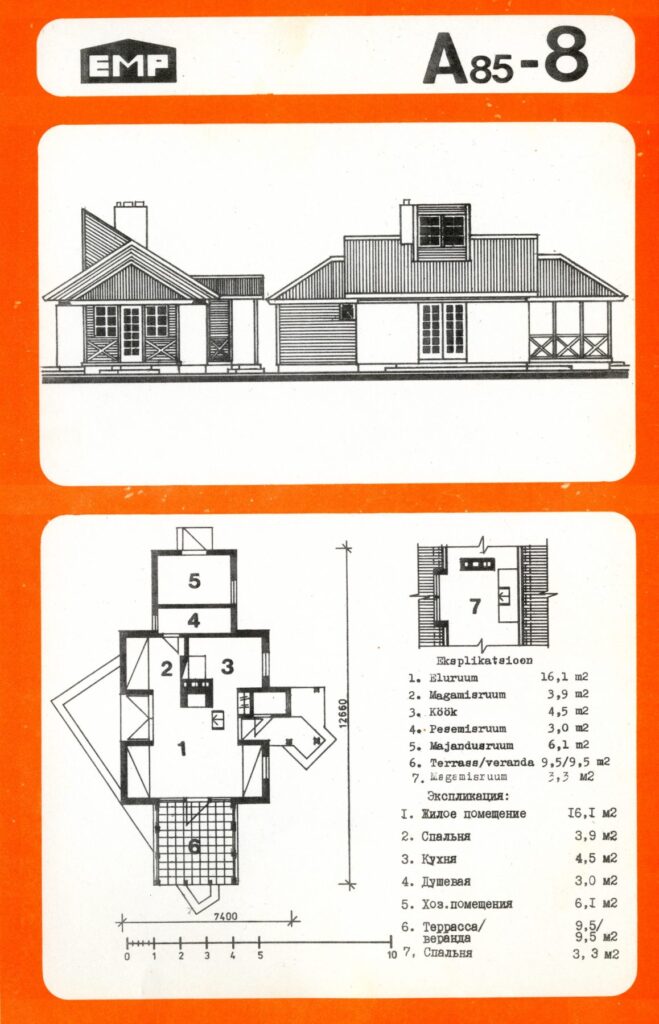

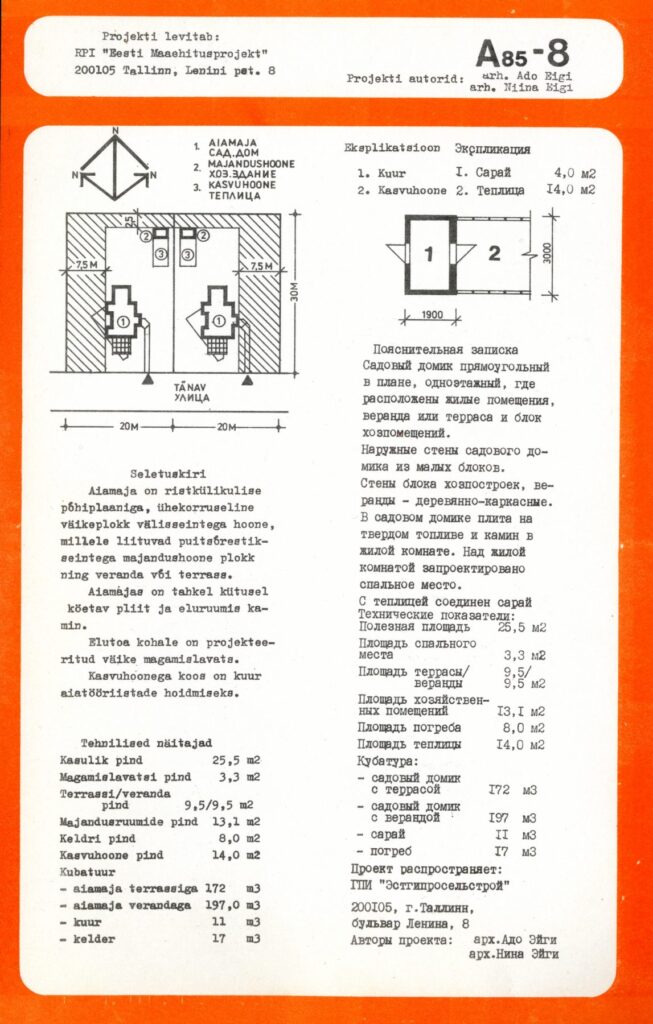

Eesti Maaehitusprojekt (Estonian Rural Design), 1980s. MEA

Standard designs of Eesti Maaehitusprojekt

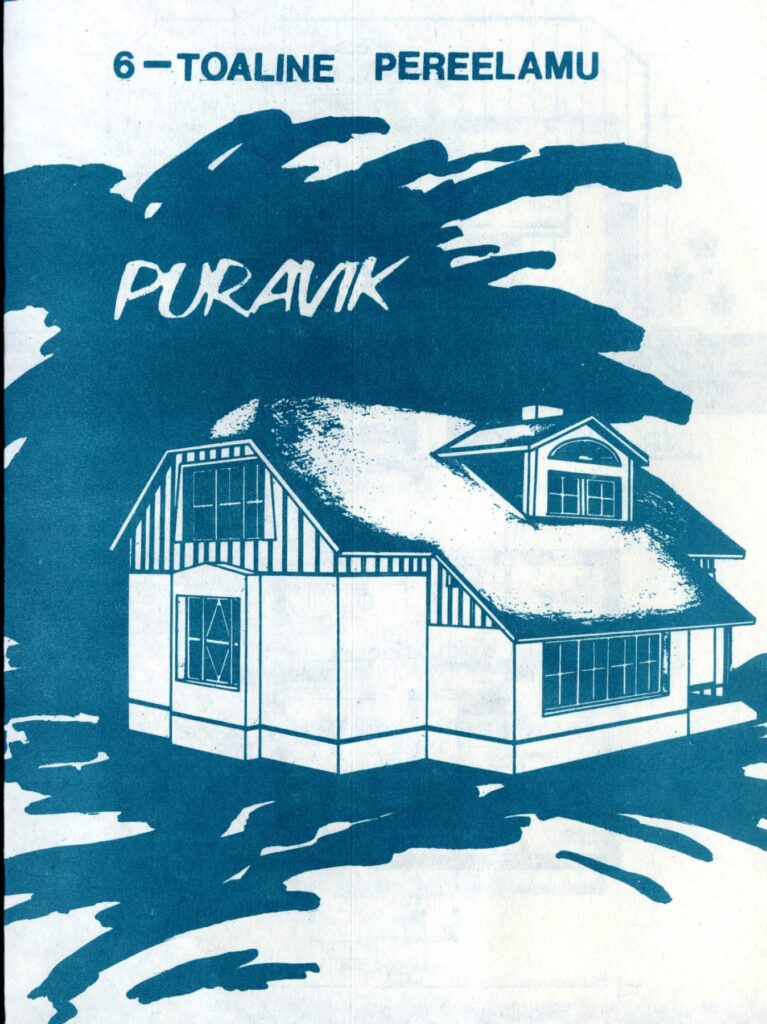

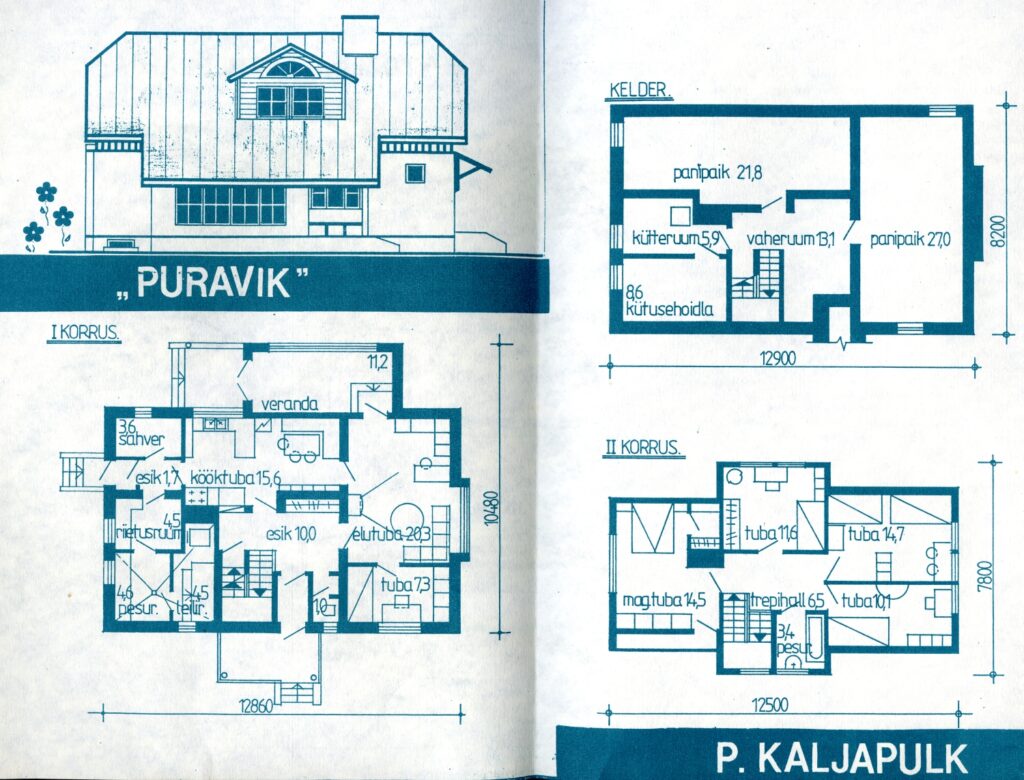

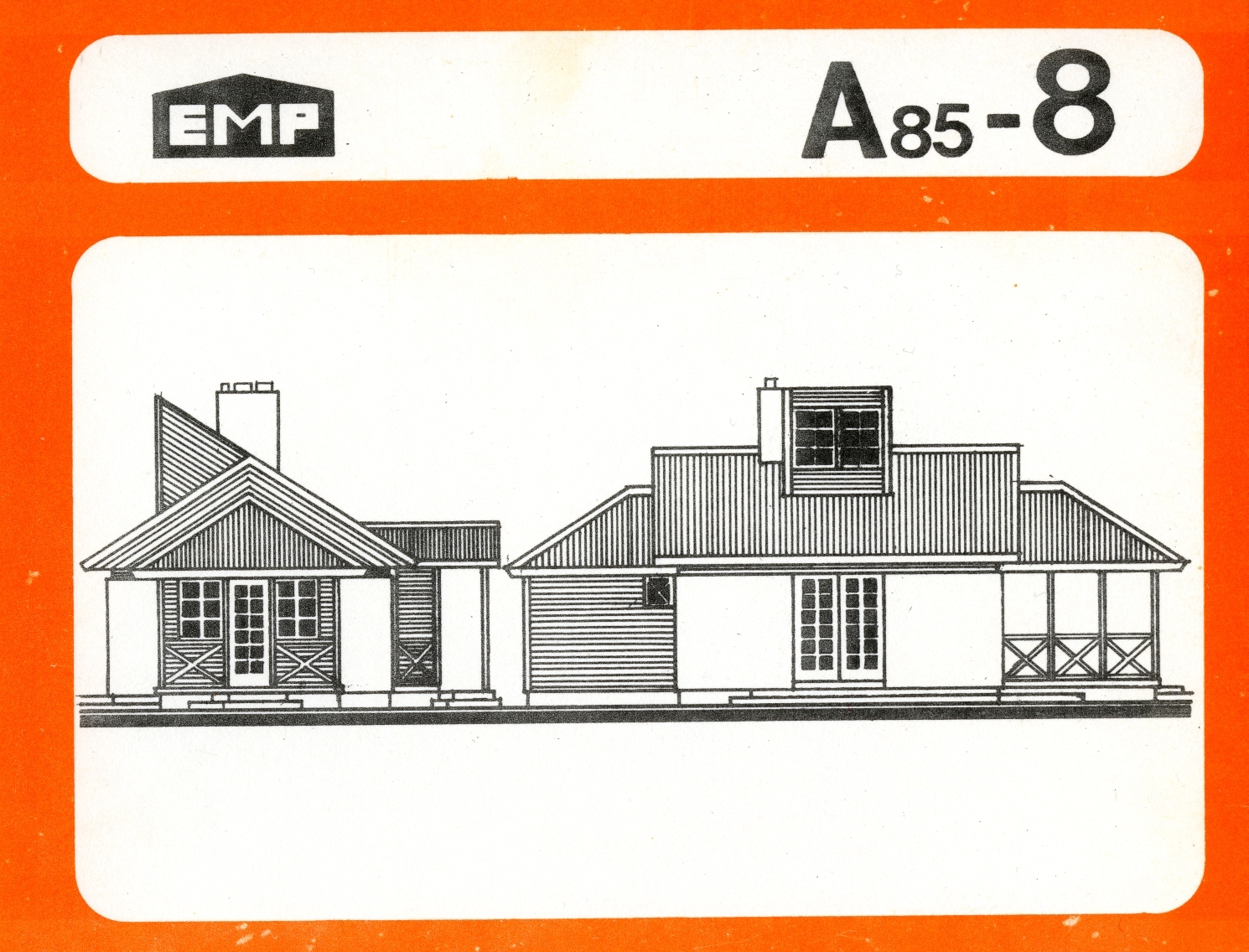

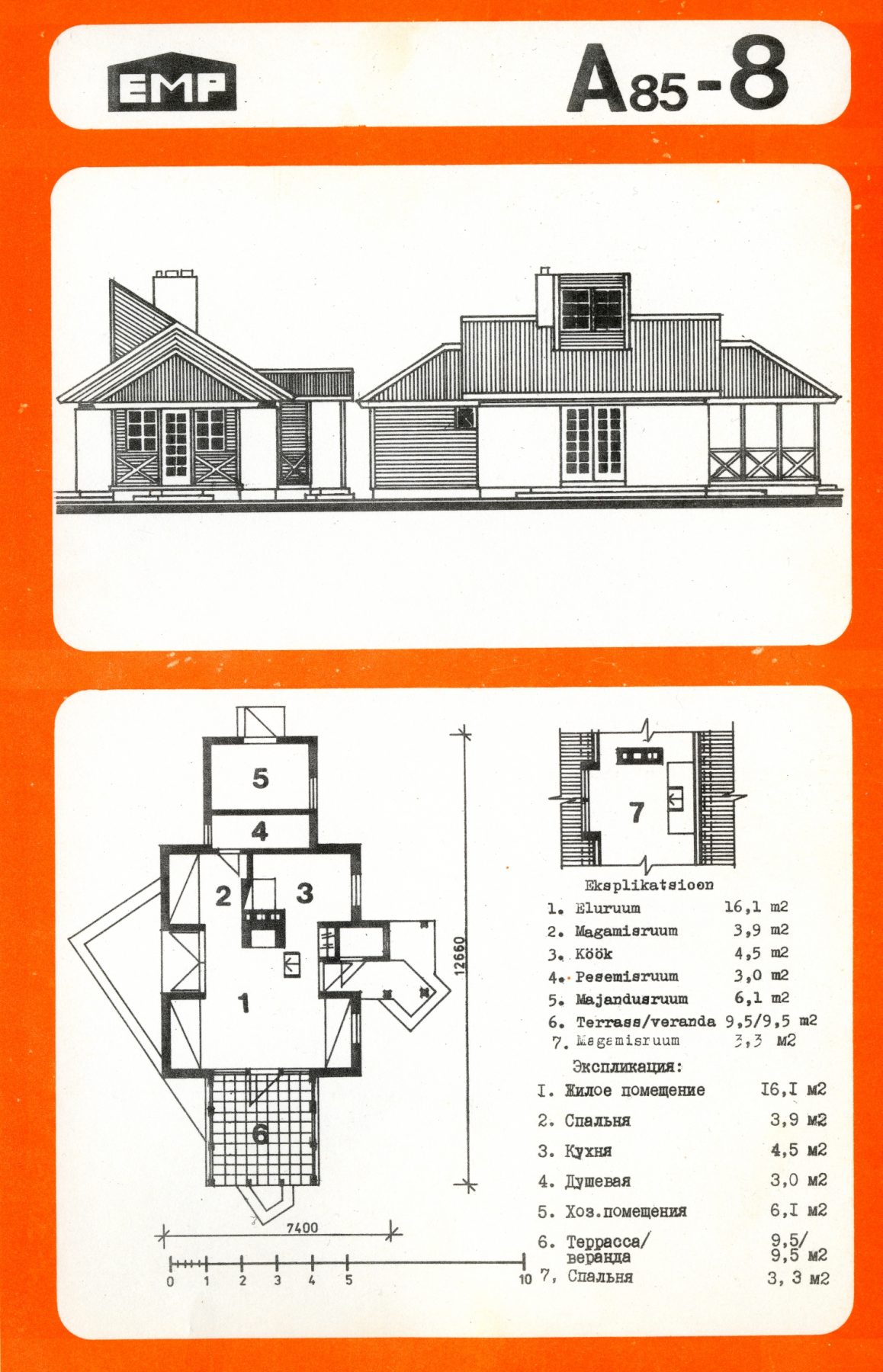

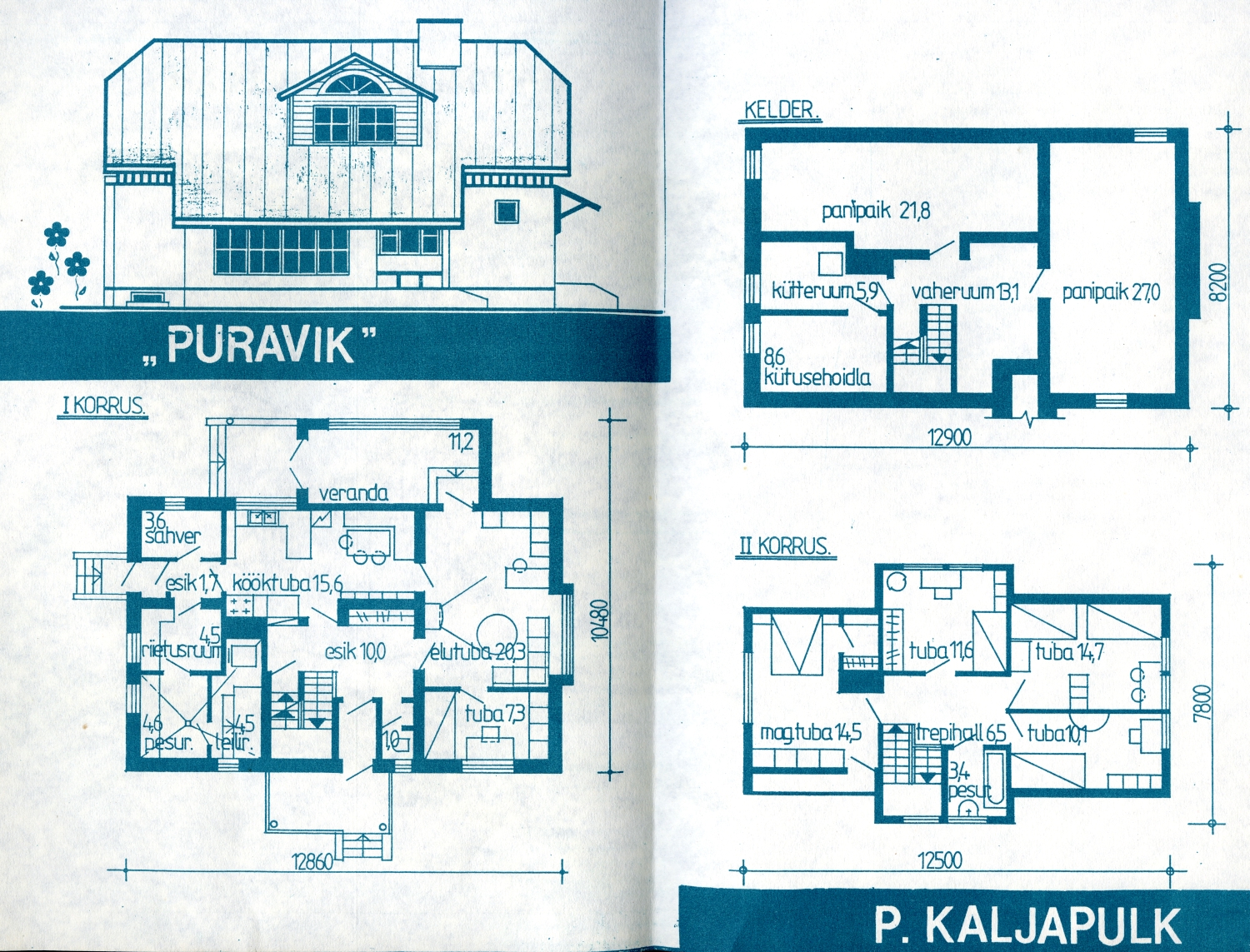

Like previously introduced “EKE Projekt” the design institute “Eesti Maaehitusprojekt” (EMP, Estonian Rural Design) also prepared plans for rural settings, starting from 1951. Designs for this widespread bureau included dwellings alongside with greenhouses and sheds. A summer cottage with a shed and a greenhouse named “A85-8” by architects Ado and Niina Eigi was part of a larger collection from series “A-85” by various architects. This 25,5 m2 building with rectangular layout came with a storage-attached greenhouse. It consists mostly of a kitchen and a living room with sleeping area. There is also a small bedroom on the upper floor below the narrow angled roof. A possibilty is offered to build either a veranda or a terrace on the shorter side of the house. Family dwelling “Puravik” (named after Boletus mushrooms) from the same period was designed by architect Priit Kaljapulk in 1989. It has a fully built basement and consists of six rooms for living, in addition of such spaces as pantry and sauna. Other models designed at the same time were named in a similarly interesting style such as “Bruce”, “No-Spa” and “Programm”. The museum has collection of over 20 leaflets made for “EMP”. Text: Maria Pöppönen

EKE Projekt, 1970–1980. MEA

Standard designs of houses and summer cottages

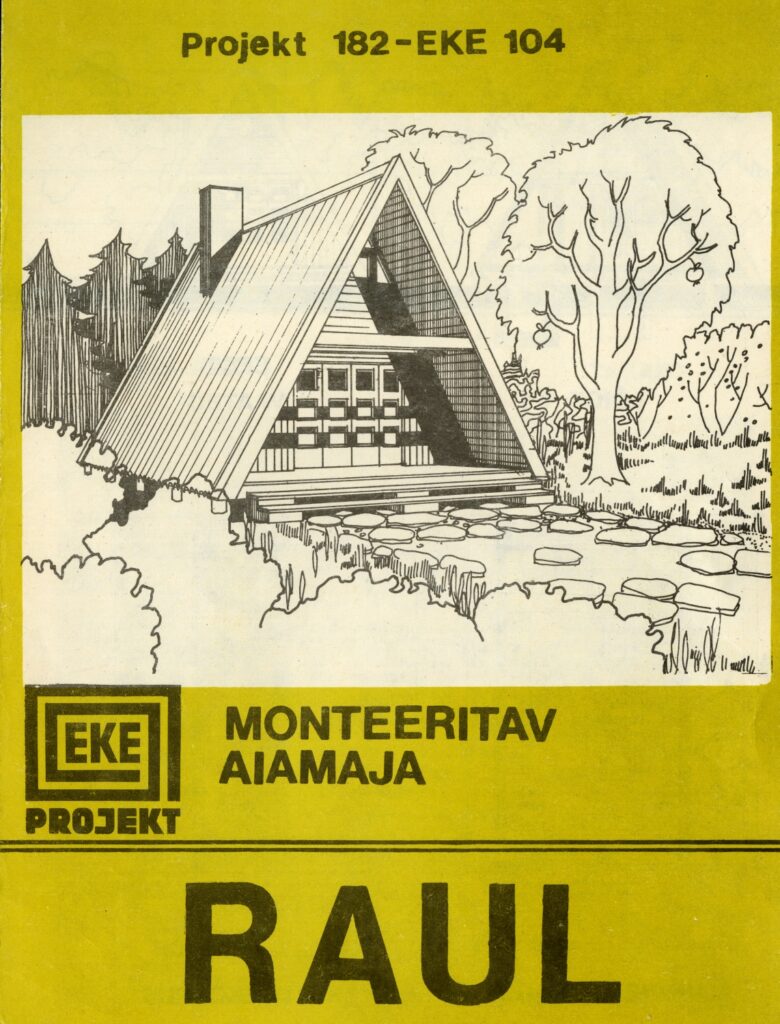

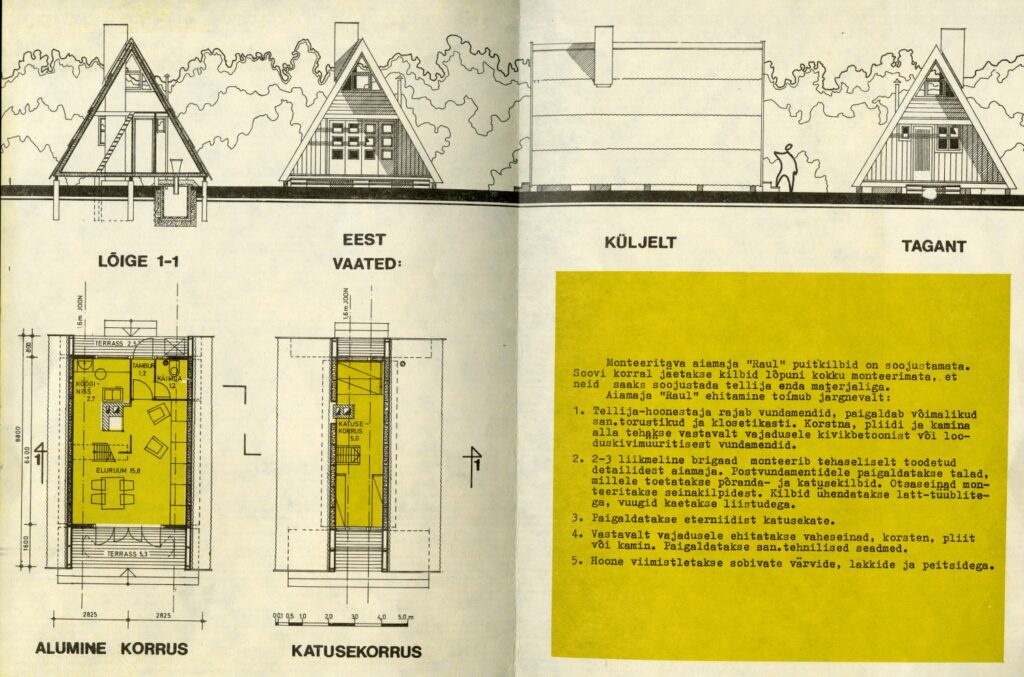

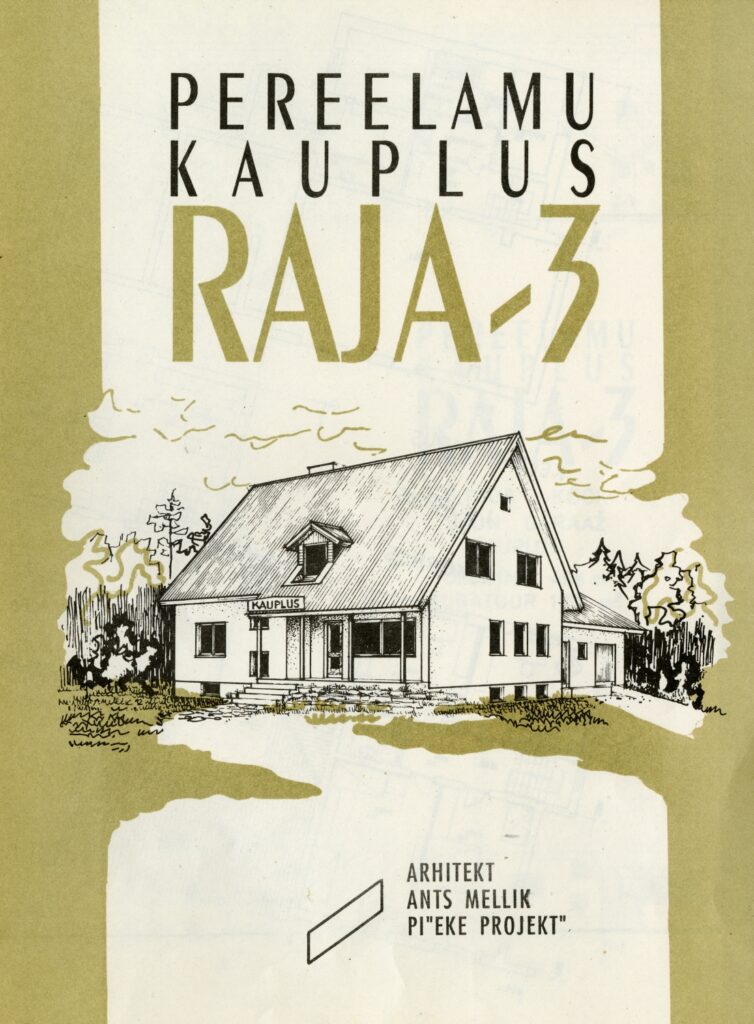

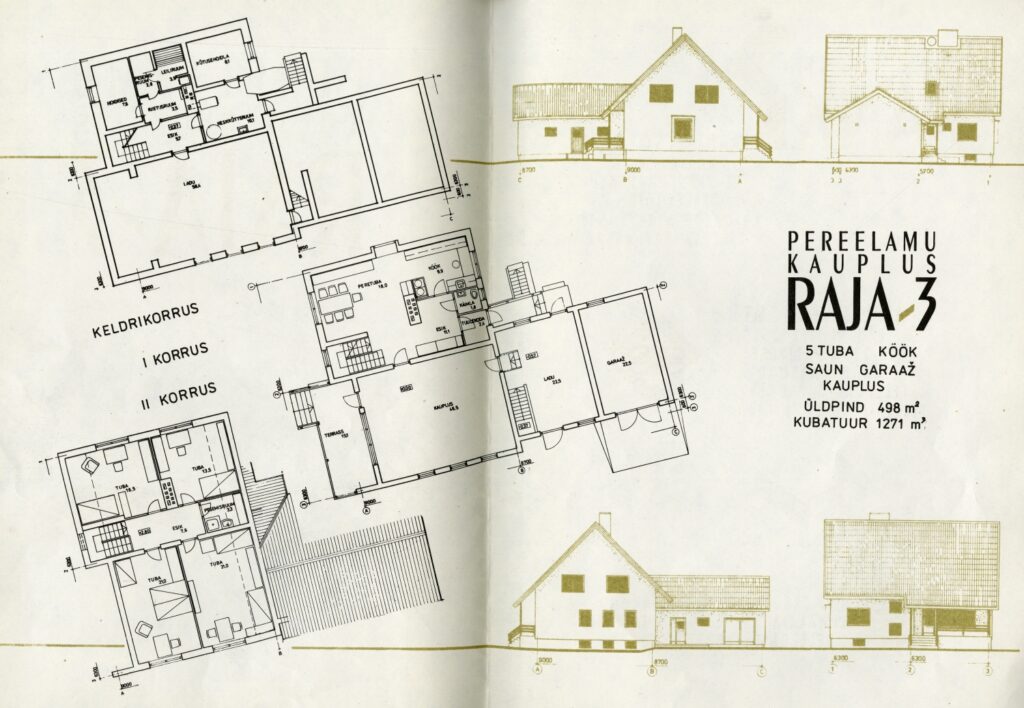

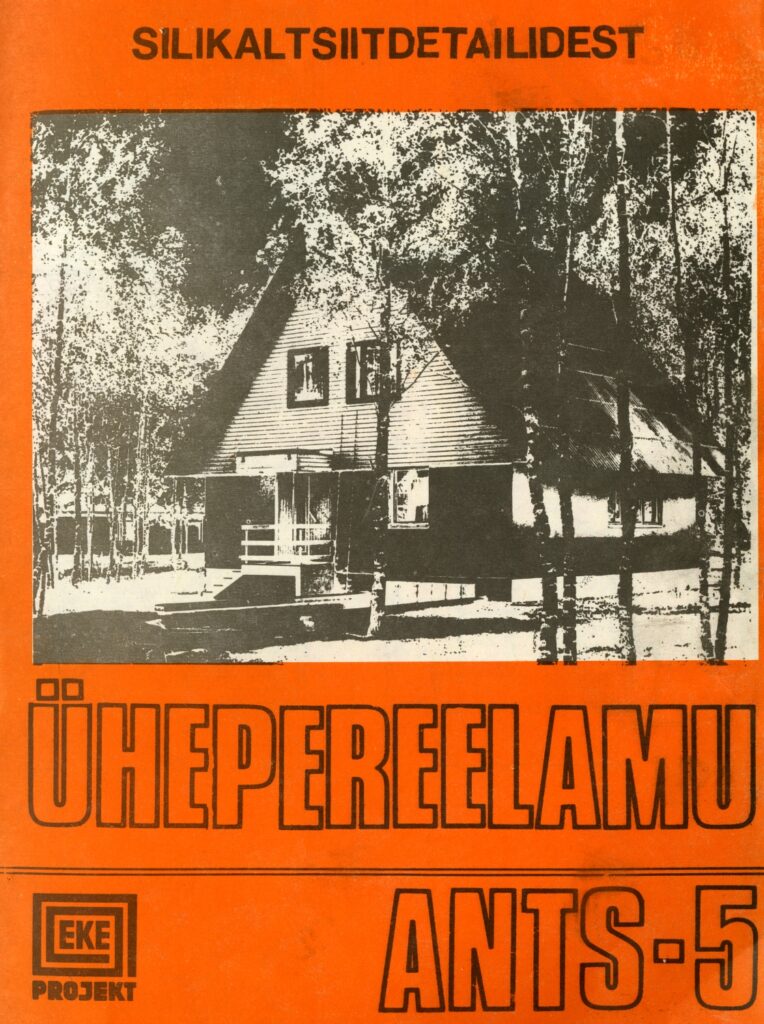

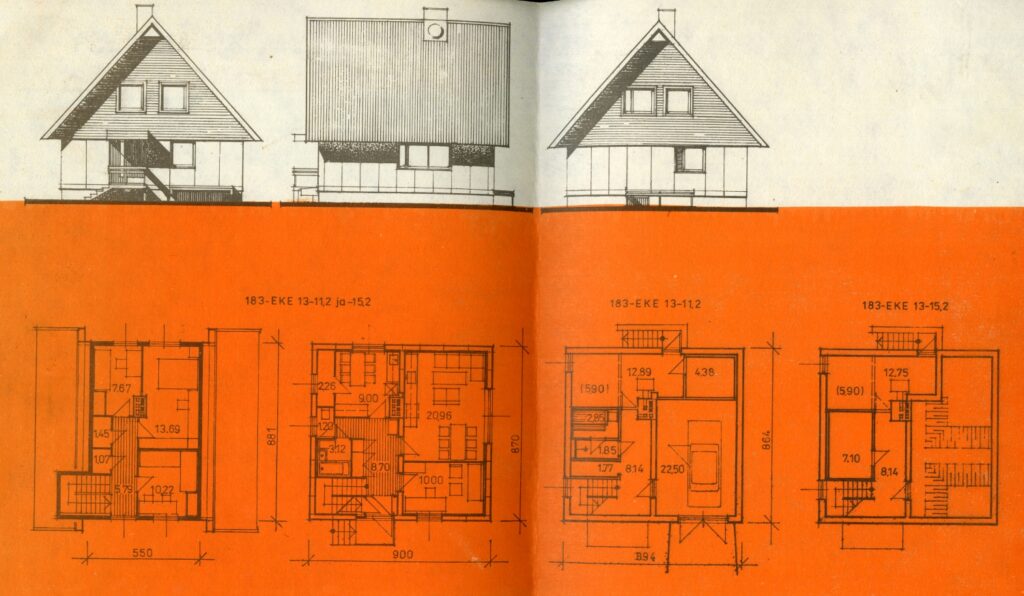

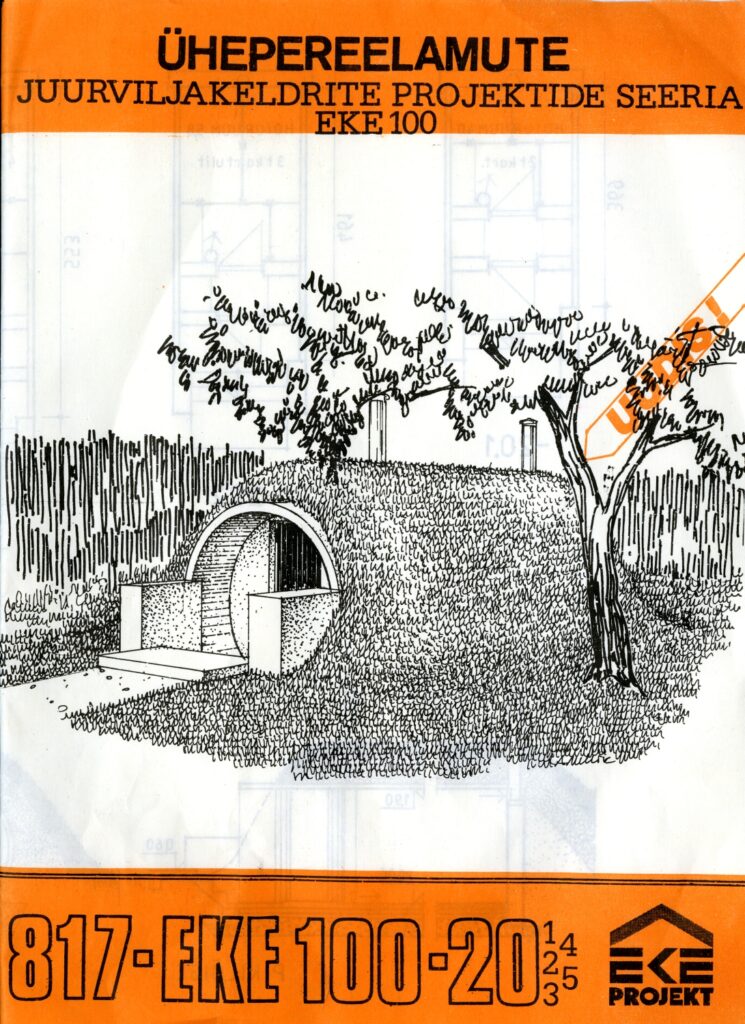

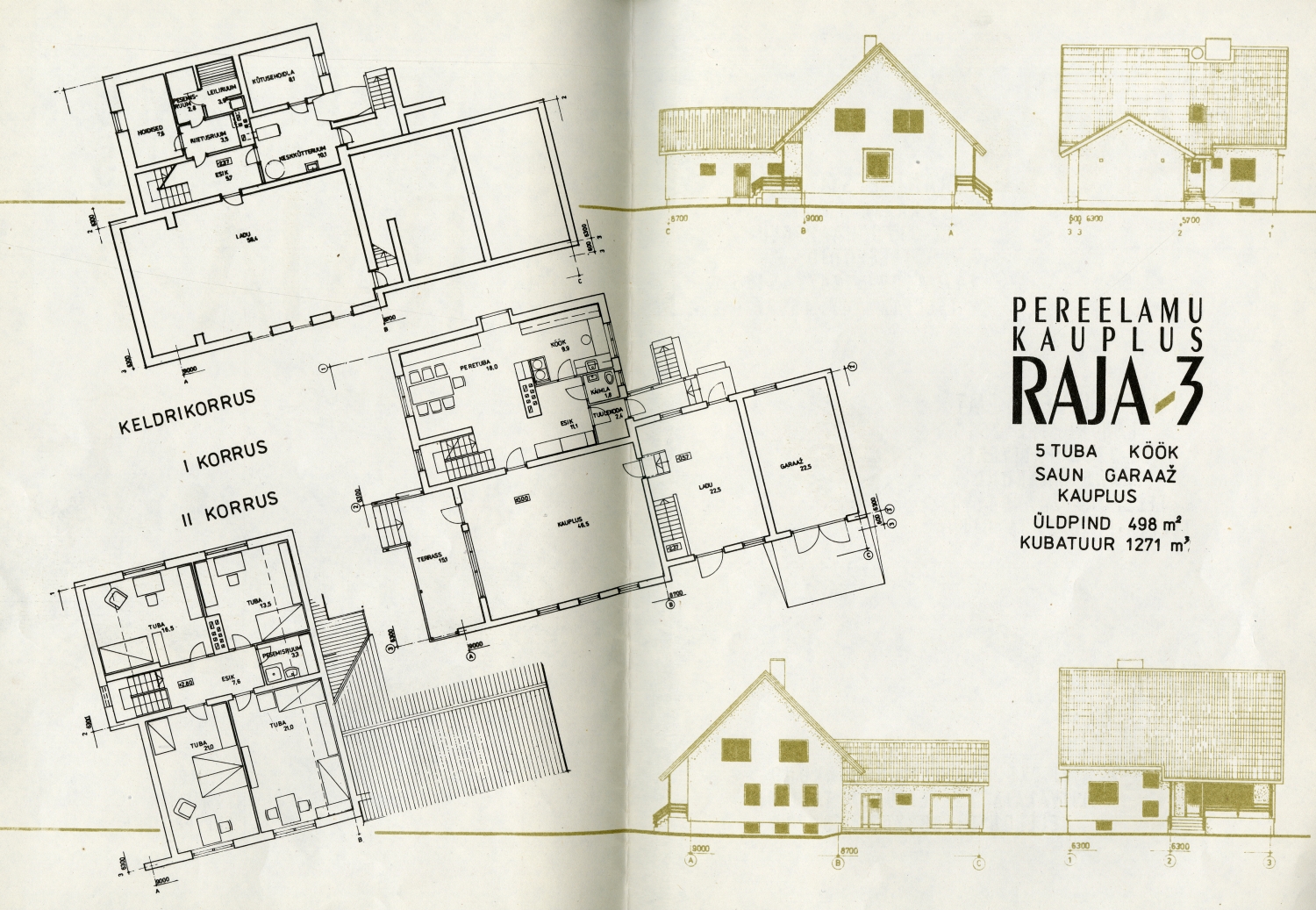

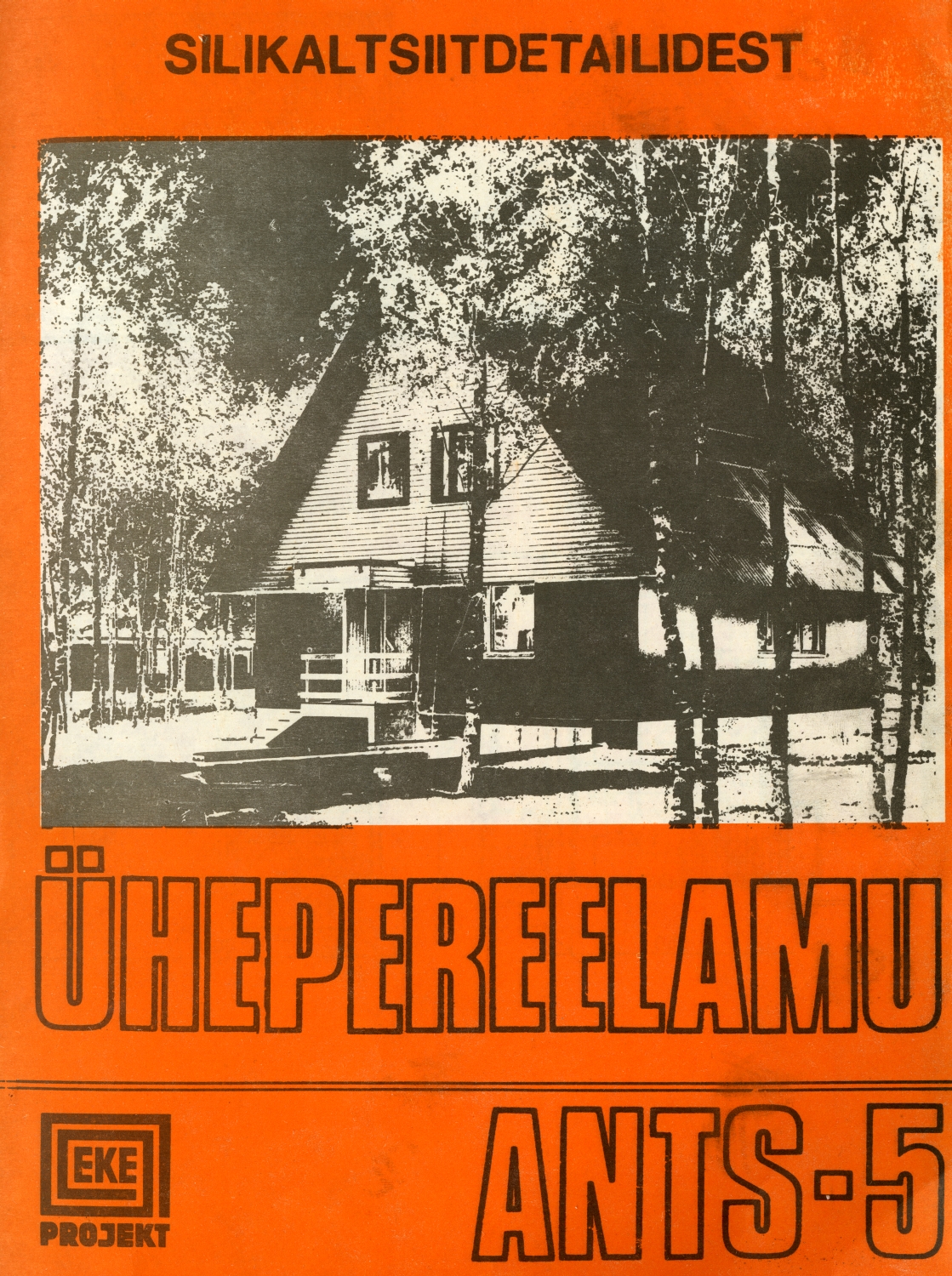

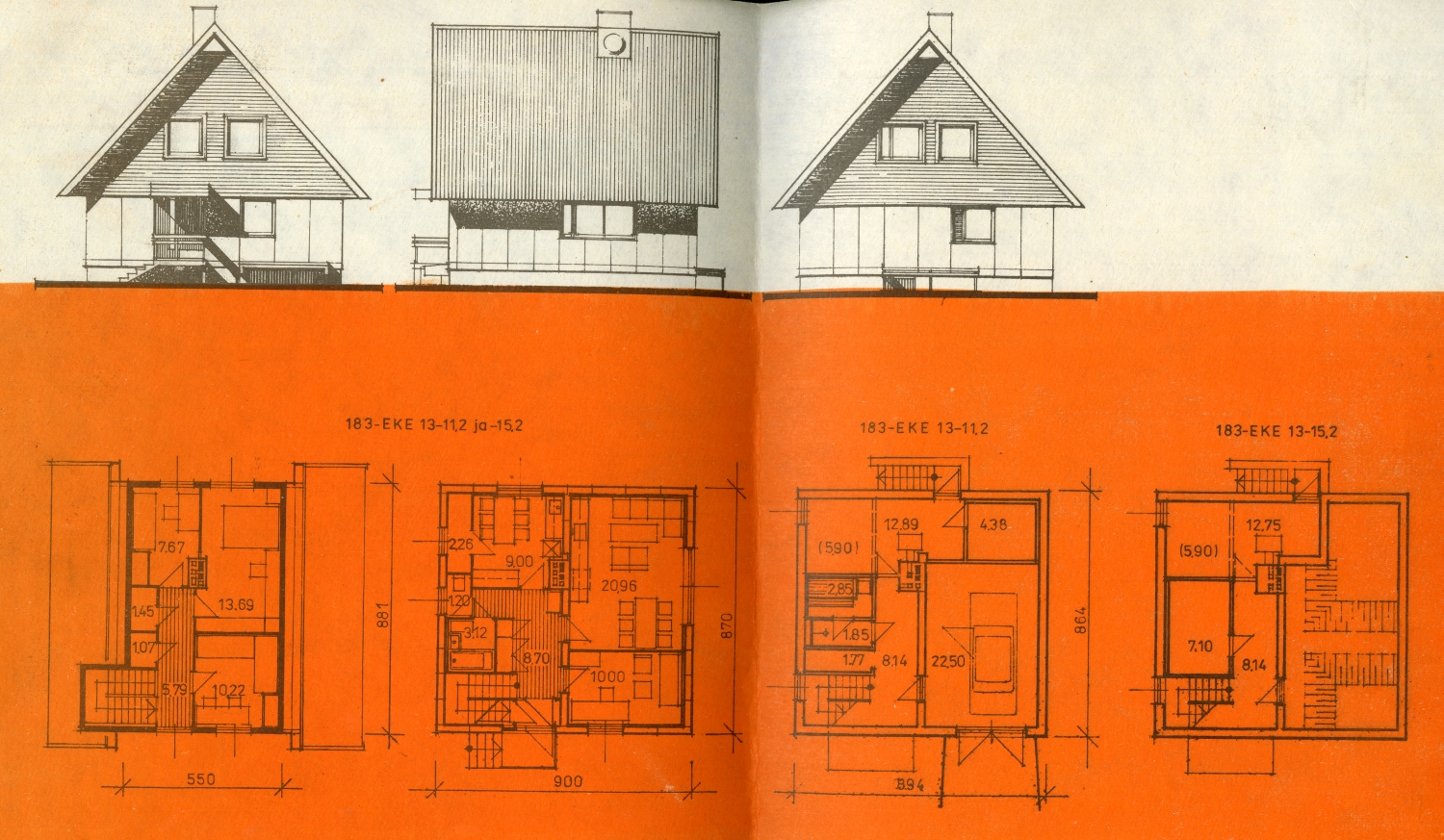

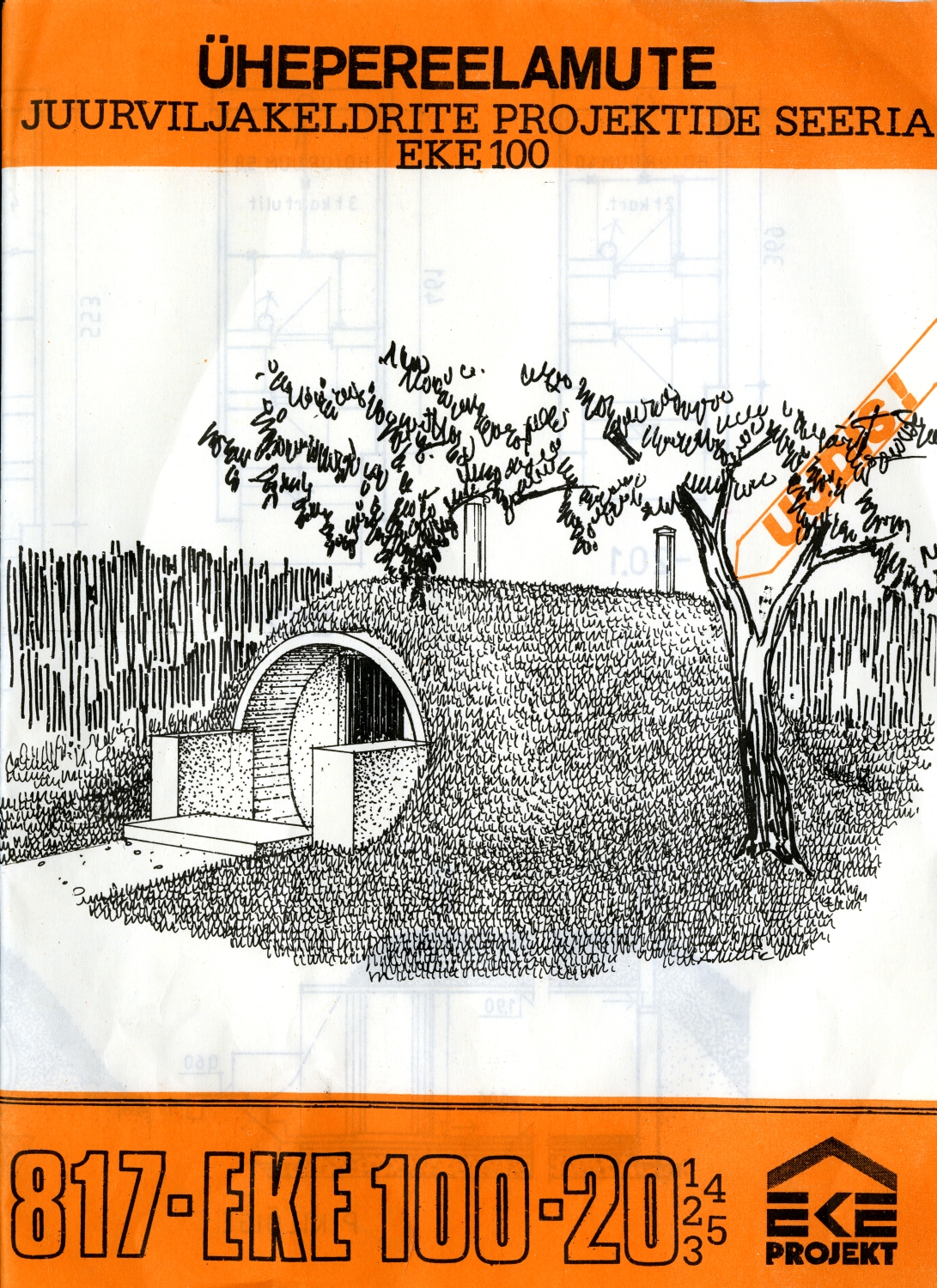

The “EKE Projekt” was founded by inter-collective-farm construction company in 1966; it was based on co-operative ownership that lasted for 1992. The bureau was focused on rural architecture. Here on four hand-outs are some of the buildings designed by “EKE Projekt” to help homeowners and cooperatives pick a house. The project’s plans varied – from dwellings to shops and root cellars.

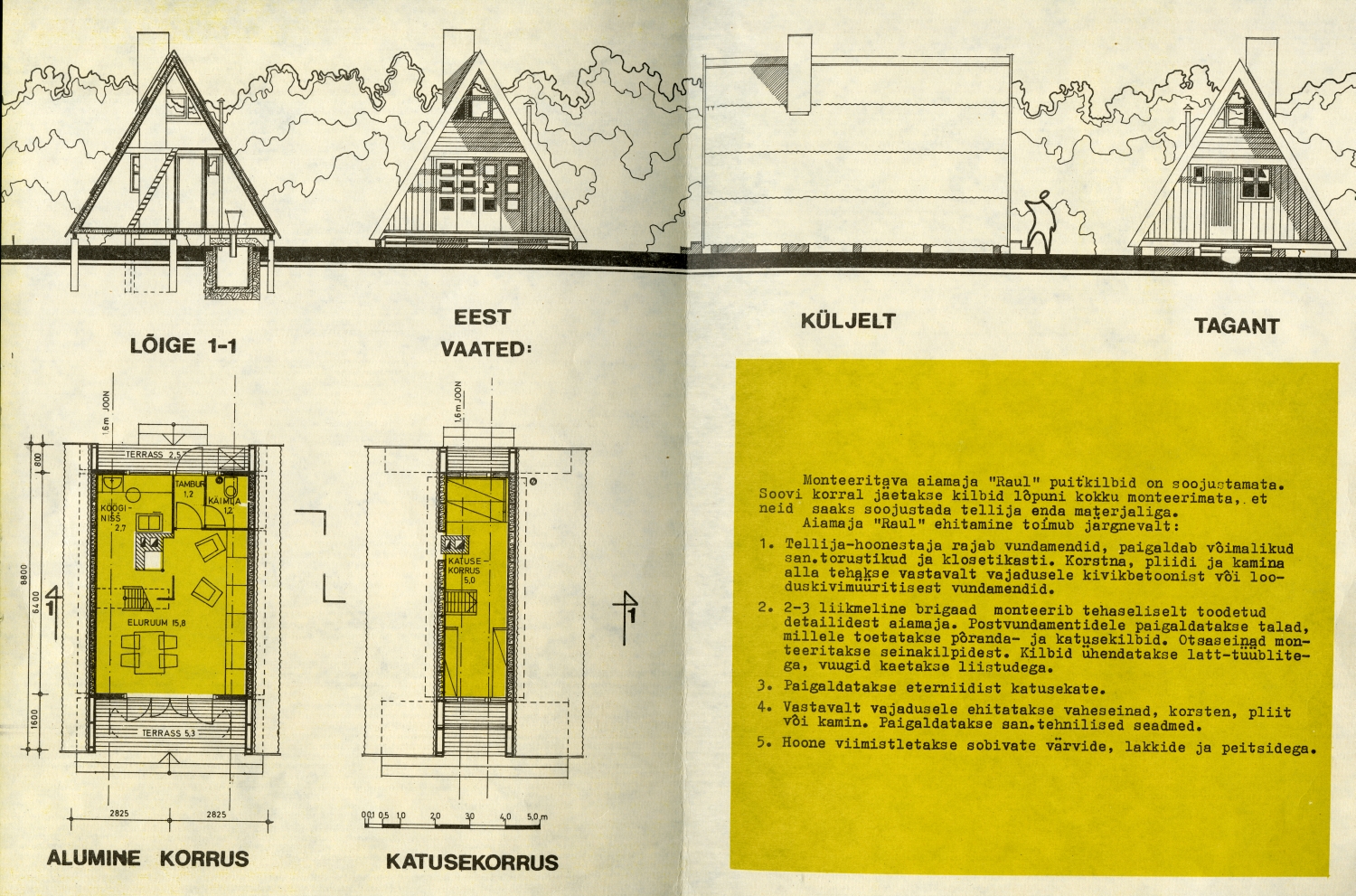

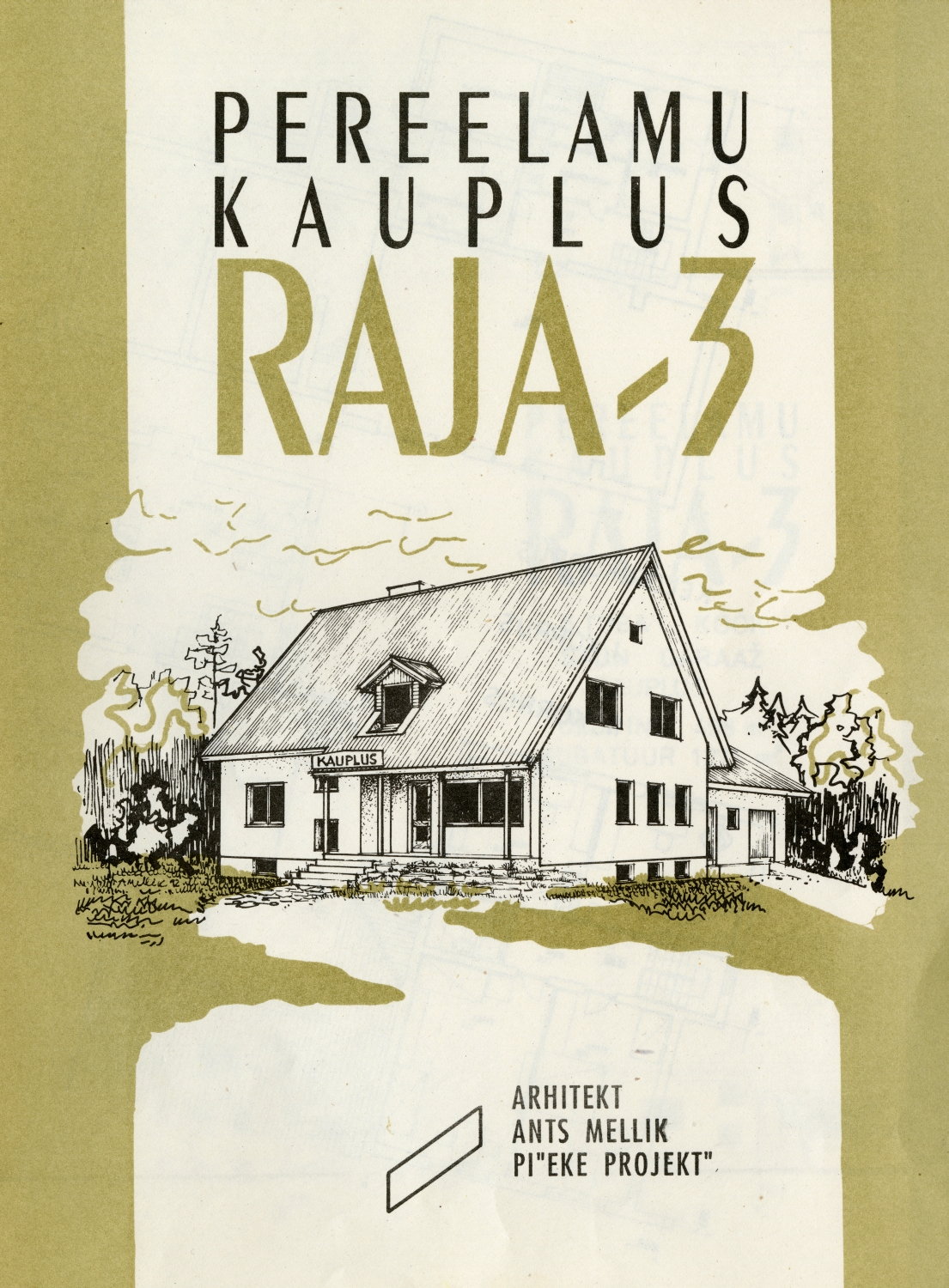

One of the main ideas of the prefabricated cabin Raul was to be easily built (engineer Rein Randväli). Known for its triangular structure, this small building had two levels: lower of which included living room, kitchenette and a toilet, and a small loft as the second floor. The family house and shop Raja-3 (architect Ants Mellik) had two functions combined. On the plan, the shop – along with the kitchen, family room, and garage – were situated on the ground floor, whereas the basement was used for storage space, sauna and utility rooms and the upper floor for bedrooms. Standard project for the one-family dwelling Ants-5 with five rooms comes from a rather popular series in the 1980s (designed by Ants Mellik). The façade of the house was covered by a combination of silicate and wooden lining. Ants-5 had various models, which differed – for example – by the structures of their basements. The vegetable cellar for one-family building (Toomas Lukk, Ants Mellik and Jaan Mõttus) was designed to be partially underground. This cement built cellar came in five variable sizes, smaller models meant for families to use and larger to store root vegetables also for sale. The roof could be covered with humus soil or grass. There are about 100 of these hand-outs of designs made in “EKE Projekt” in the museum collection. Text: Maria Pöppönen

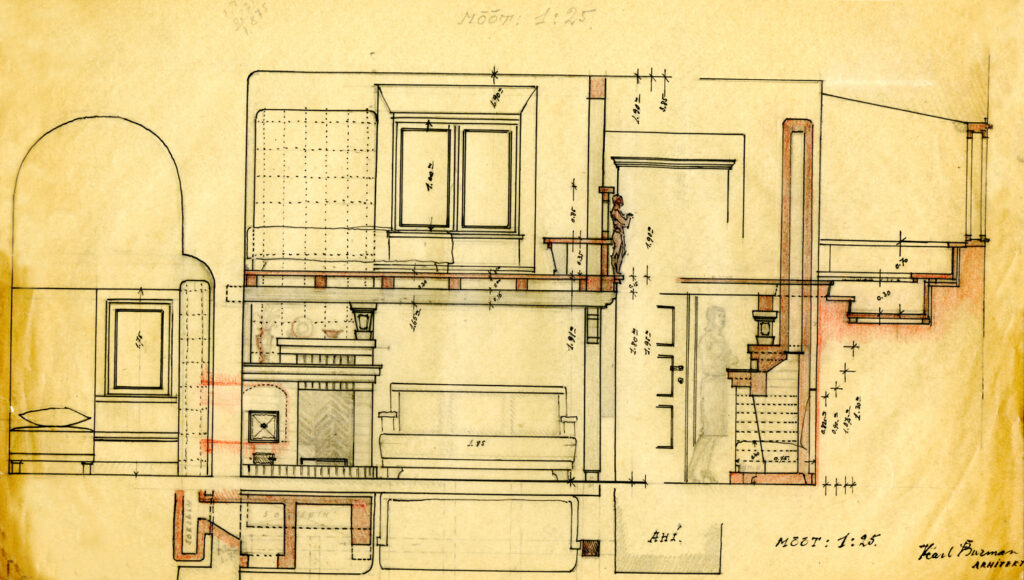

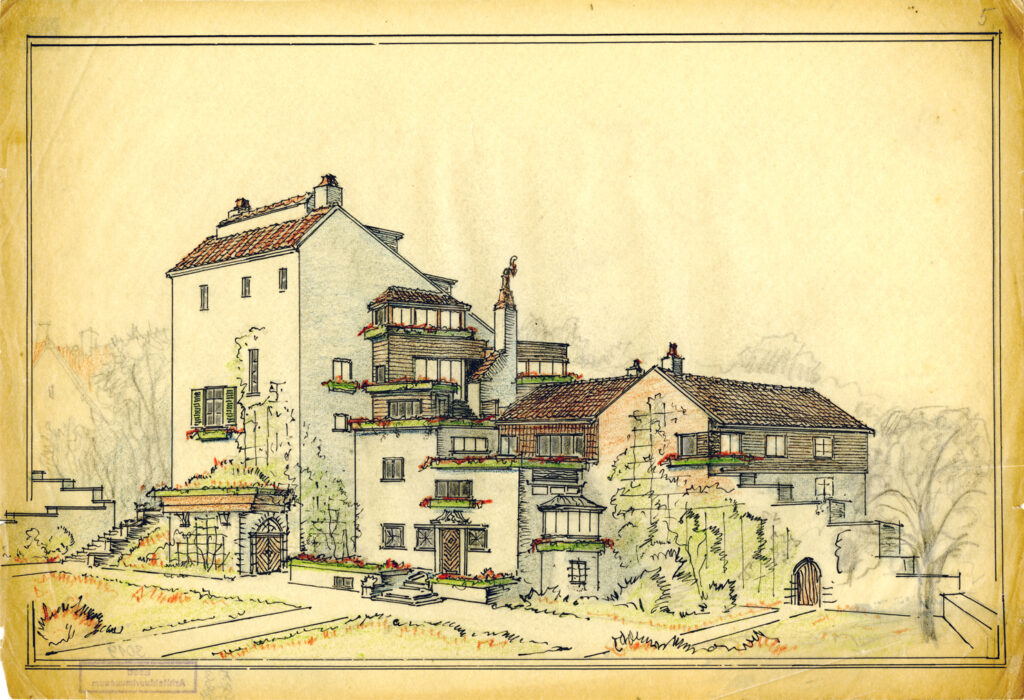

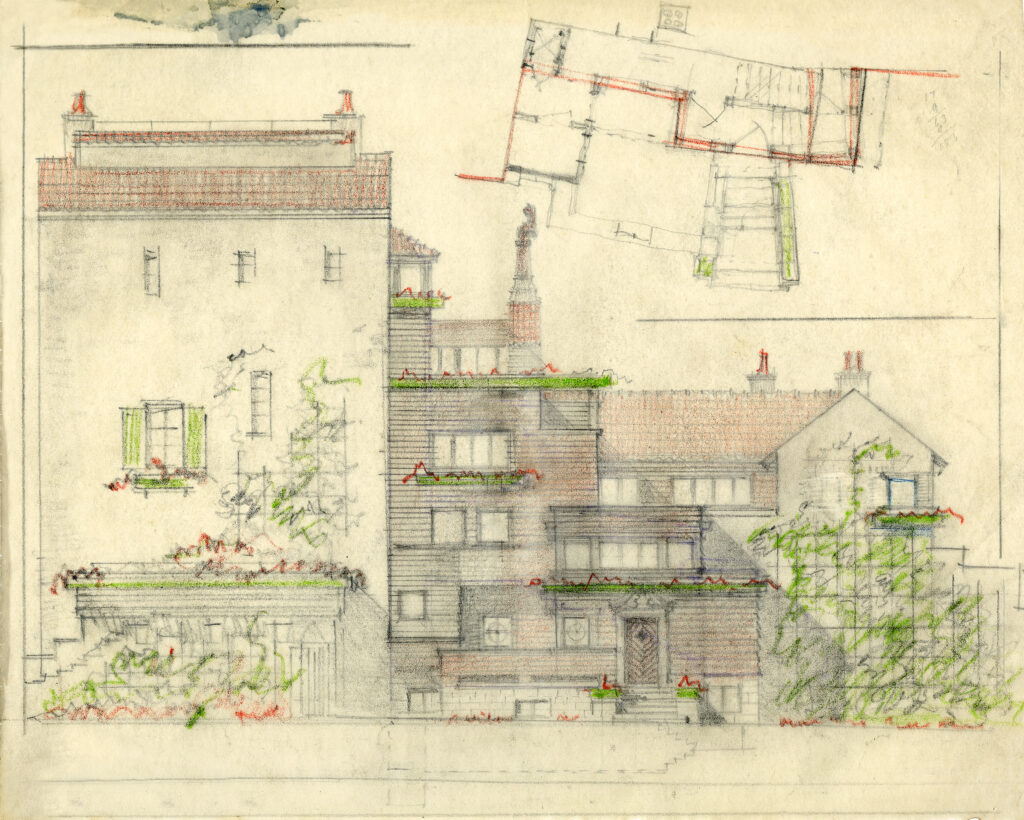

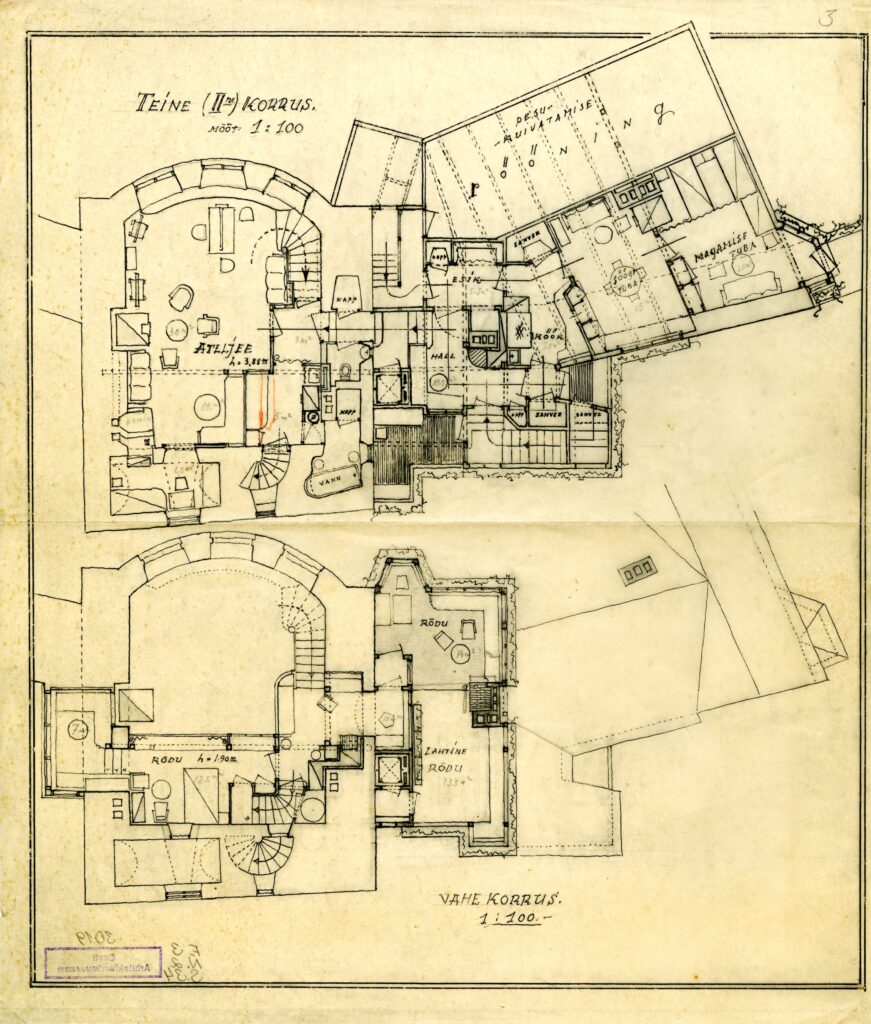

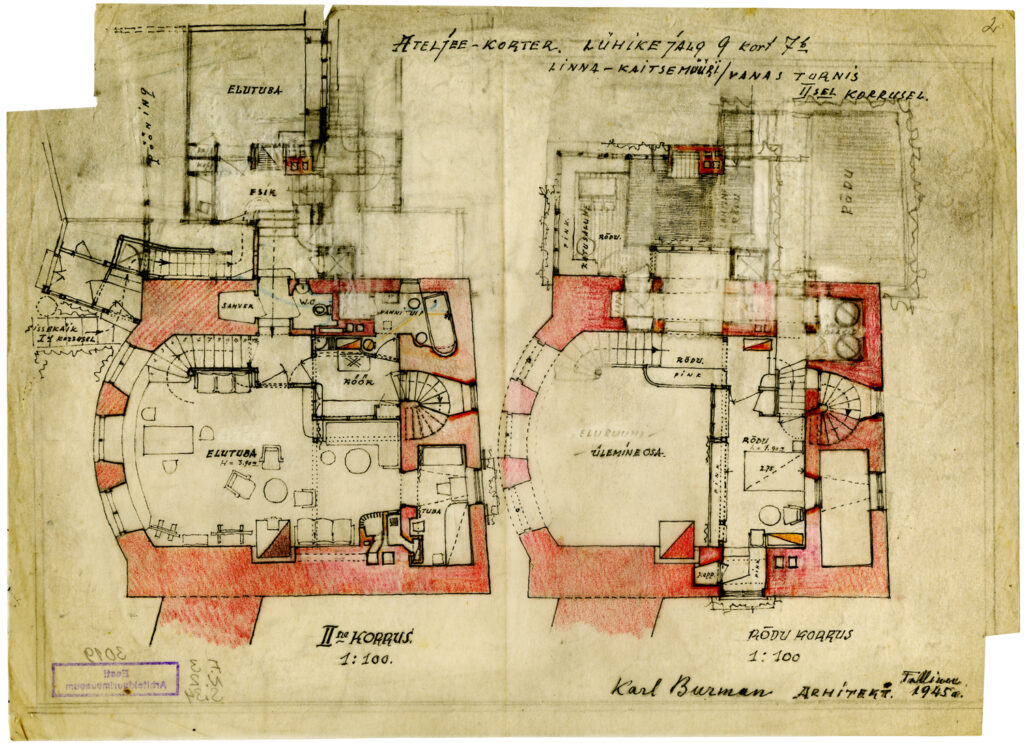

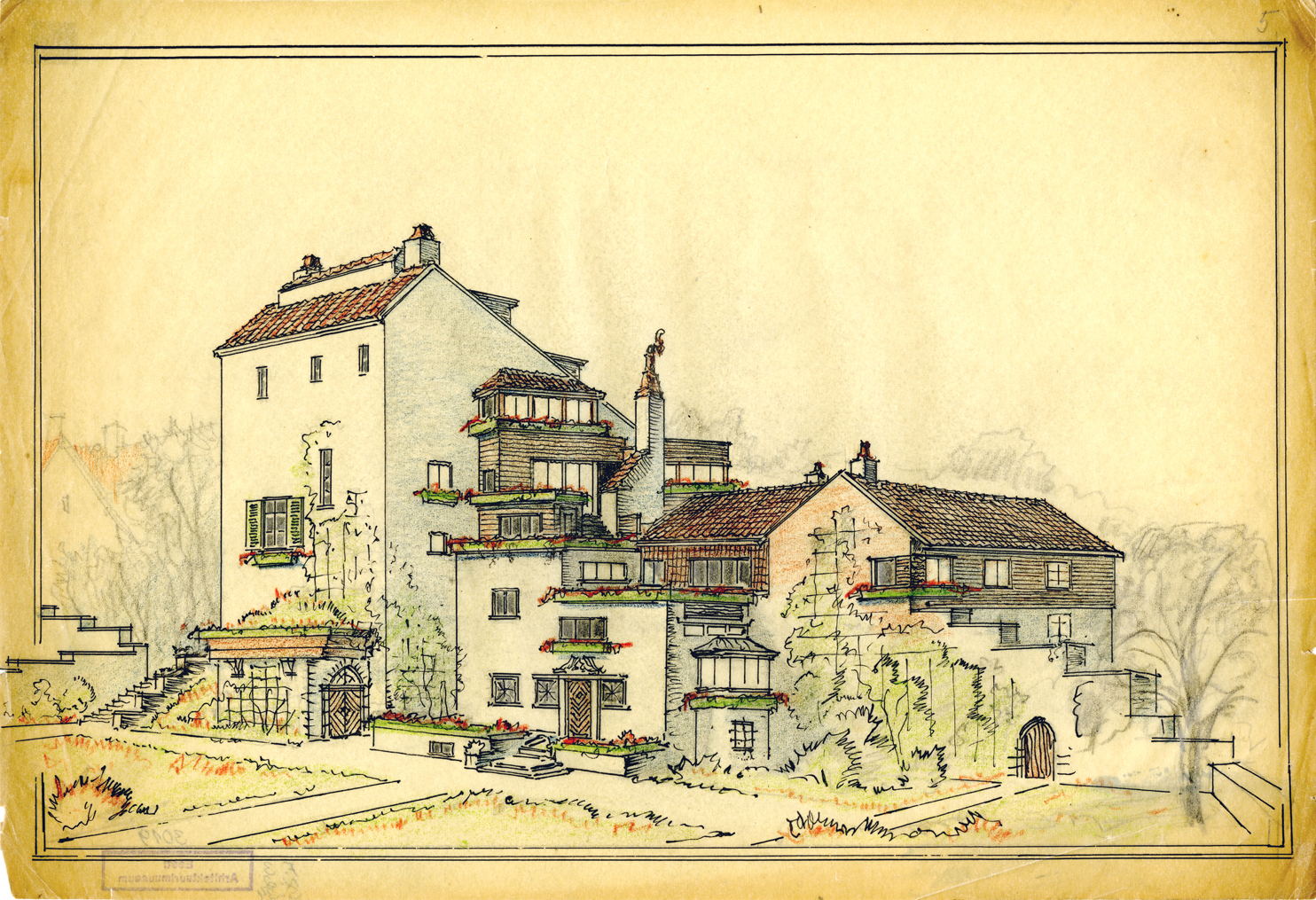

Karl Burman, 1945–1947. MEA 3.2.34

Reconstruction of the Neitsitorn tower into a studio apartment

Artist-architect Karl Burman lost his home in Kadriorg during the war and received new rooms in Neitsitorn (the Virgin’s Tower) in Old Town Tallinn, which had been an established gathering place for artists for a long time. The top floors of the tower housed a studio and living quarters. For 20 years the famous architect lived in a small one-room apartment within the thick walls of the medieval wall tower and planned to carry out reconstructions during his time there. In the sketches, Karl Burman has depicted the tower as a southern villa with spacious balconies and skylights, he also covered the façades with lush climbing plants. Every corner has been put into use – benches and built-in cupboards designed for the niches. The tower was restored and reconstructed as a cafeteria in 1968–1980. The drawings came to the museum via architect Teddy Böckler in 1994. Text: Sandra Mälk

-

-

Lighting design for the bank building in Tartu

Aarne Mõttus (drawing), Arnold Matteus, Karl Burman. MEA 2.3.49

Lighting design for the bank building in Tartu

In 1936 the people of Tartu named the building of the Tartu branch of Eesti Pank (Bank of Estonia) (designed by Arnold Matteus and Karl Burman) as one of the most stately-looking new structures in the city. The bronze sculptures by sculptor Juhan Raudsepp add to the artistic integrity of the presentable façade. It was no coincidence that this bank building was also chosen as one of the public buildings to be decorated for the 20th anniversary of the Republic of Estonia. The lighting design for the façade, overseeing the square, was prepared by graphic and scenographer Aarne Mõttus. Drawing was donated by restoration firm Pindisain Ehitus in 2001. Text: Sandra Mälk

-

-

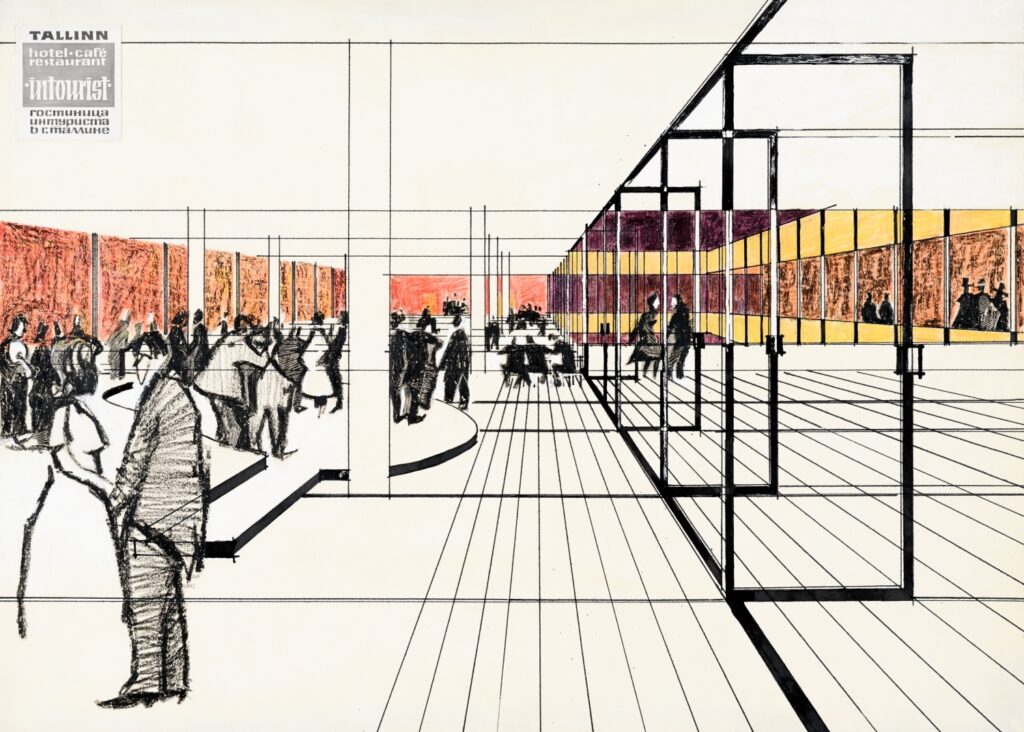

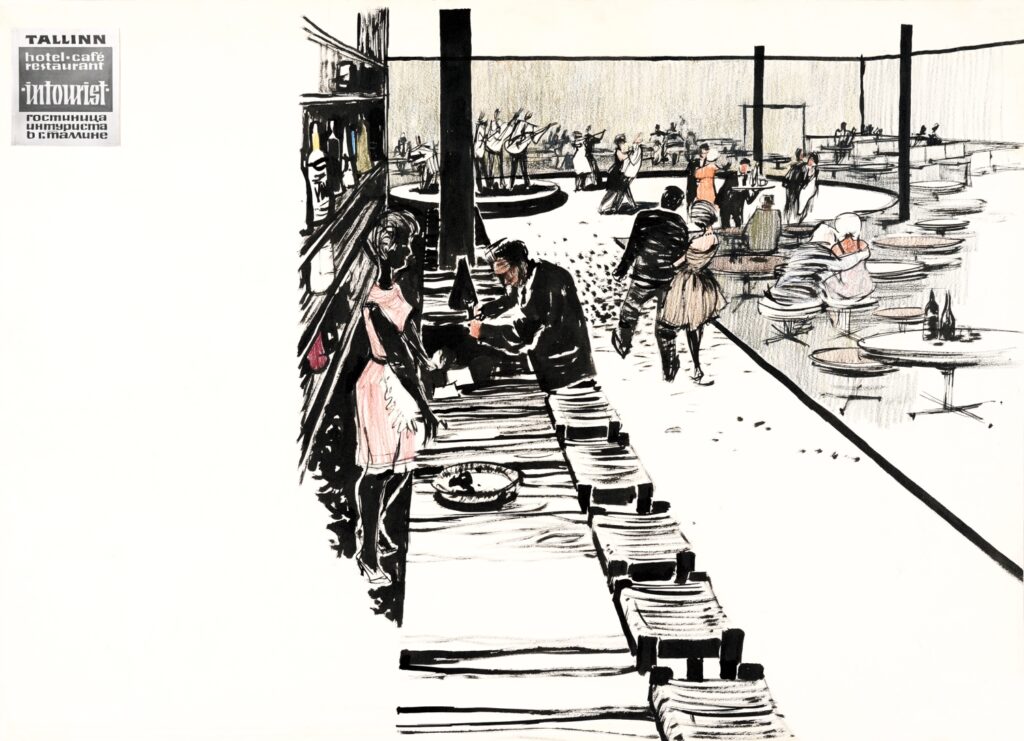

Interior design for Hotel Viru

-

-

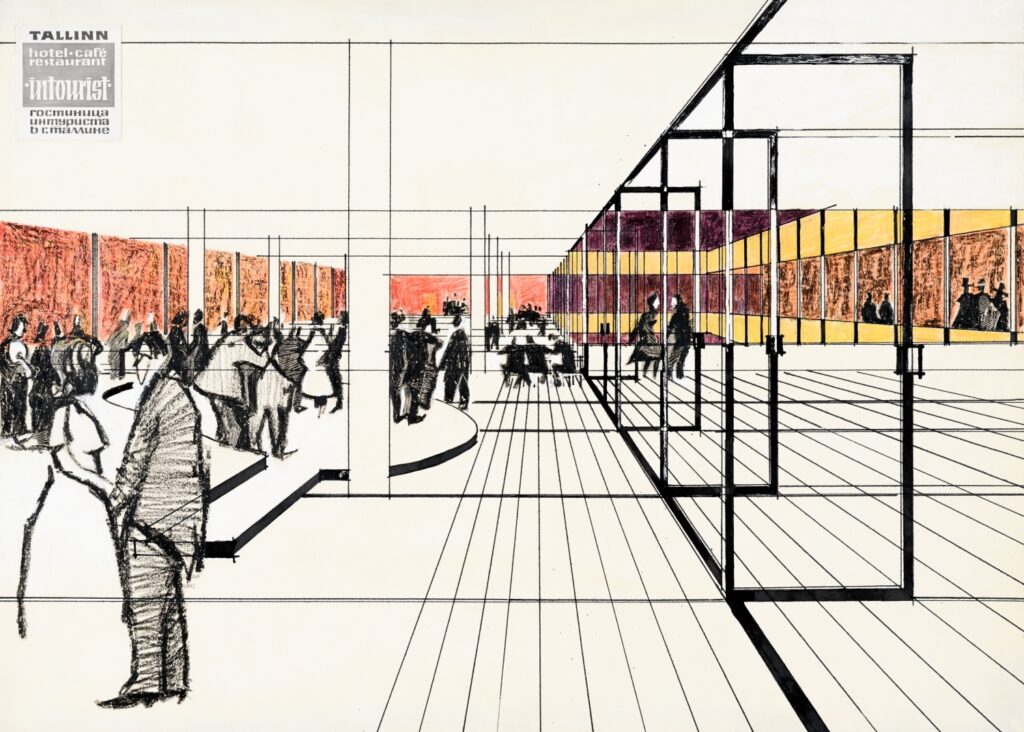

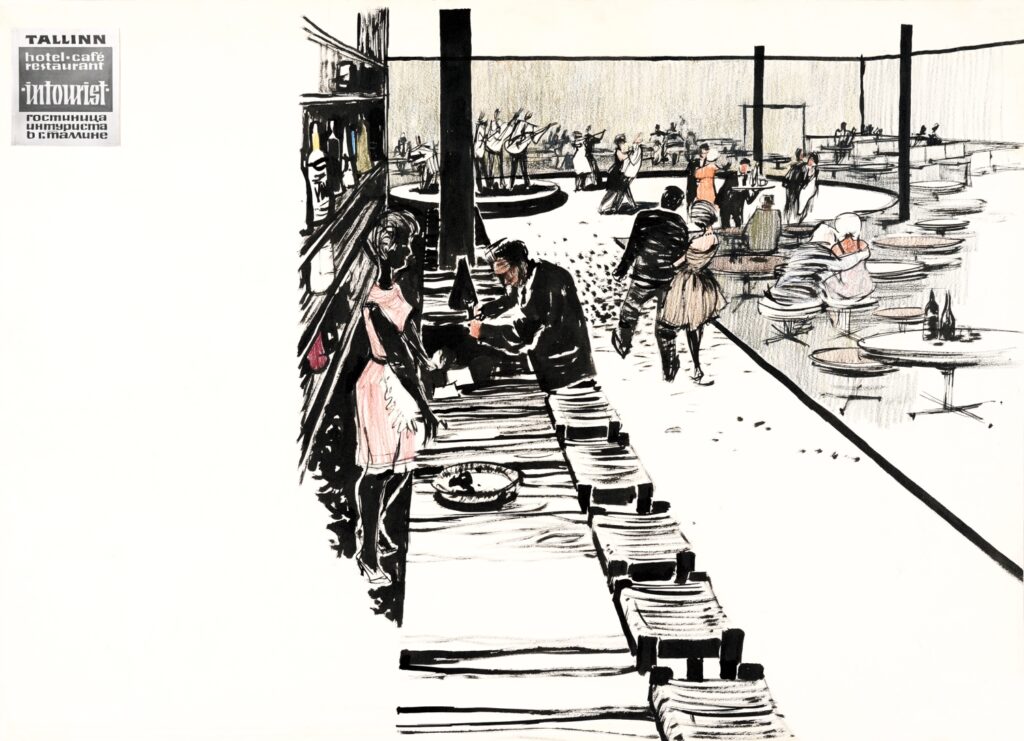

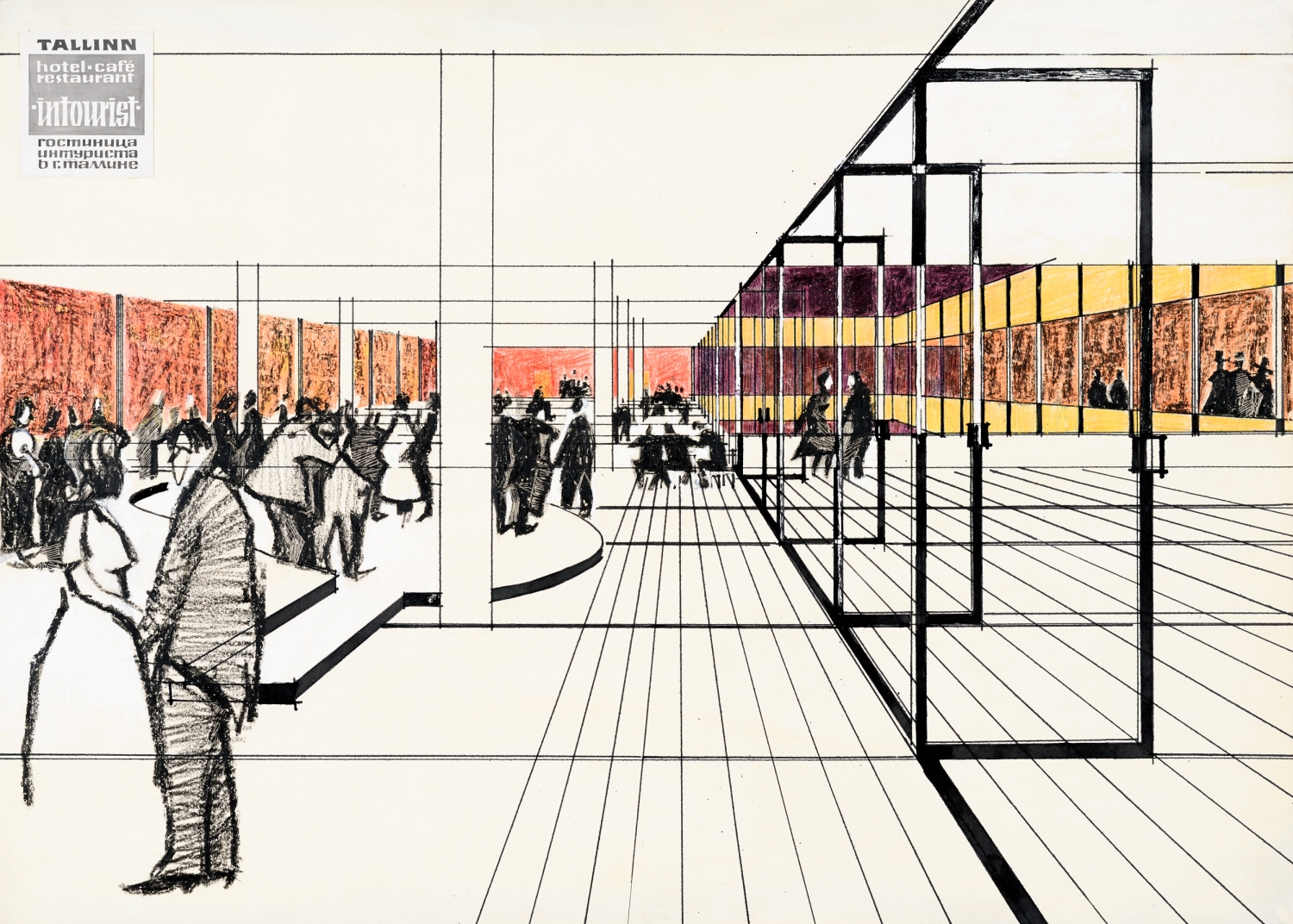

Interior design for Hotel Viru

Vello Asi, Väino Tamm, Loomet Raudsepp, 1964–1968. MEA 4.2.2

Interior design for Hotel Viru

Hotel Viru (architects Henno Sepmann, Mart Port) was the highest and most modern hotel building in Soviet Estonia. It was primarily targeted at guests from Finland because the Tallinn-Helsinki seaway was reopened in 1965. However, locals were also able to access the bars and cafés of the hotel. The drawings illustrate a restaurant and a bar on the lowest volume of the building. The simplistic style reflected in the interior and the free plan indicate influences by modern Nordic room design – the opposite approach to the extravagant decade that preceded it. Drafts for the interior of Hotel Viru were to the museum by Eesti Projekt in 1994. Text: Sandra Mälk

-

-

-

-

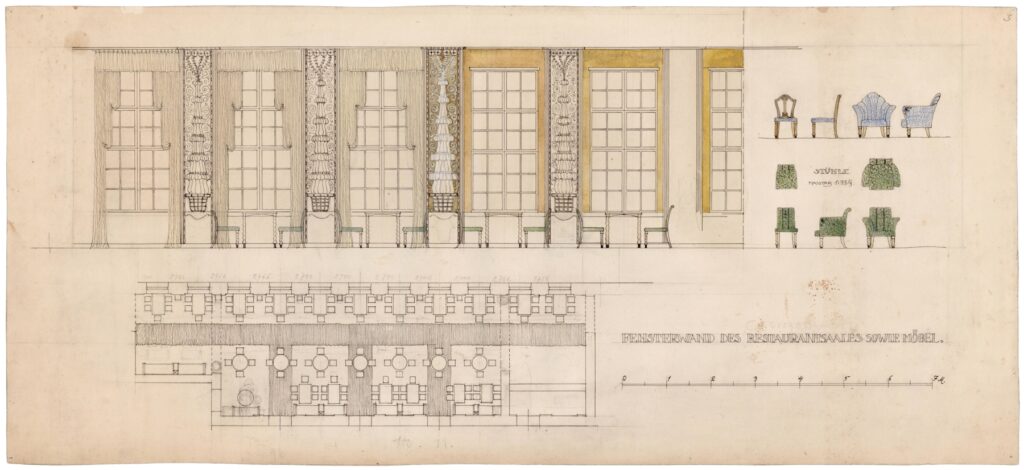

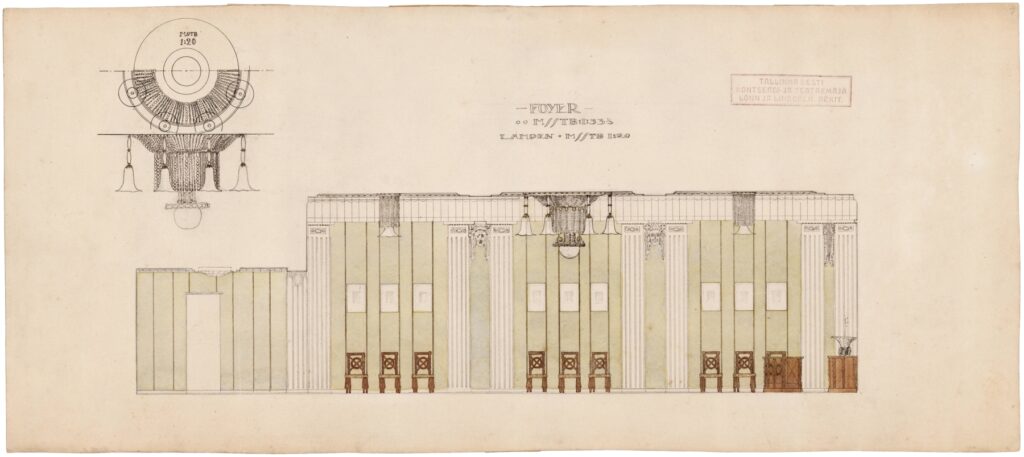

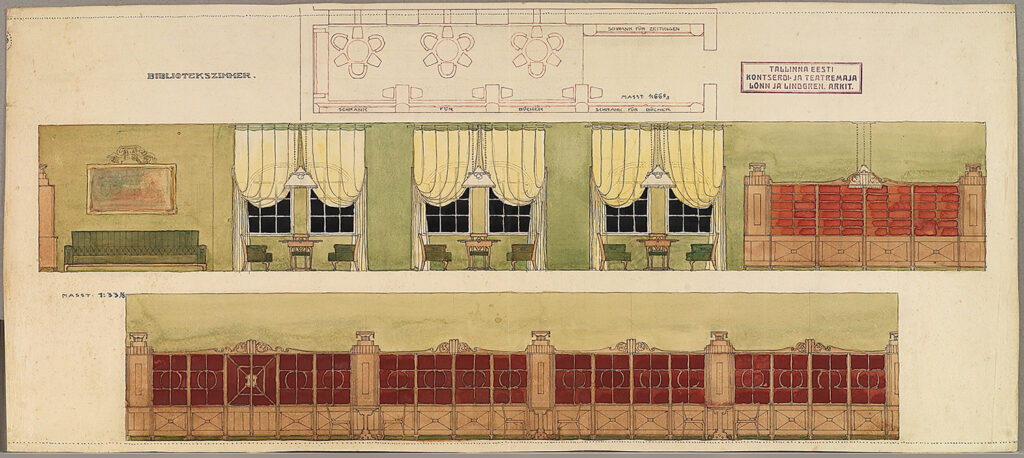

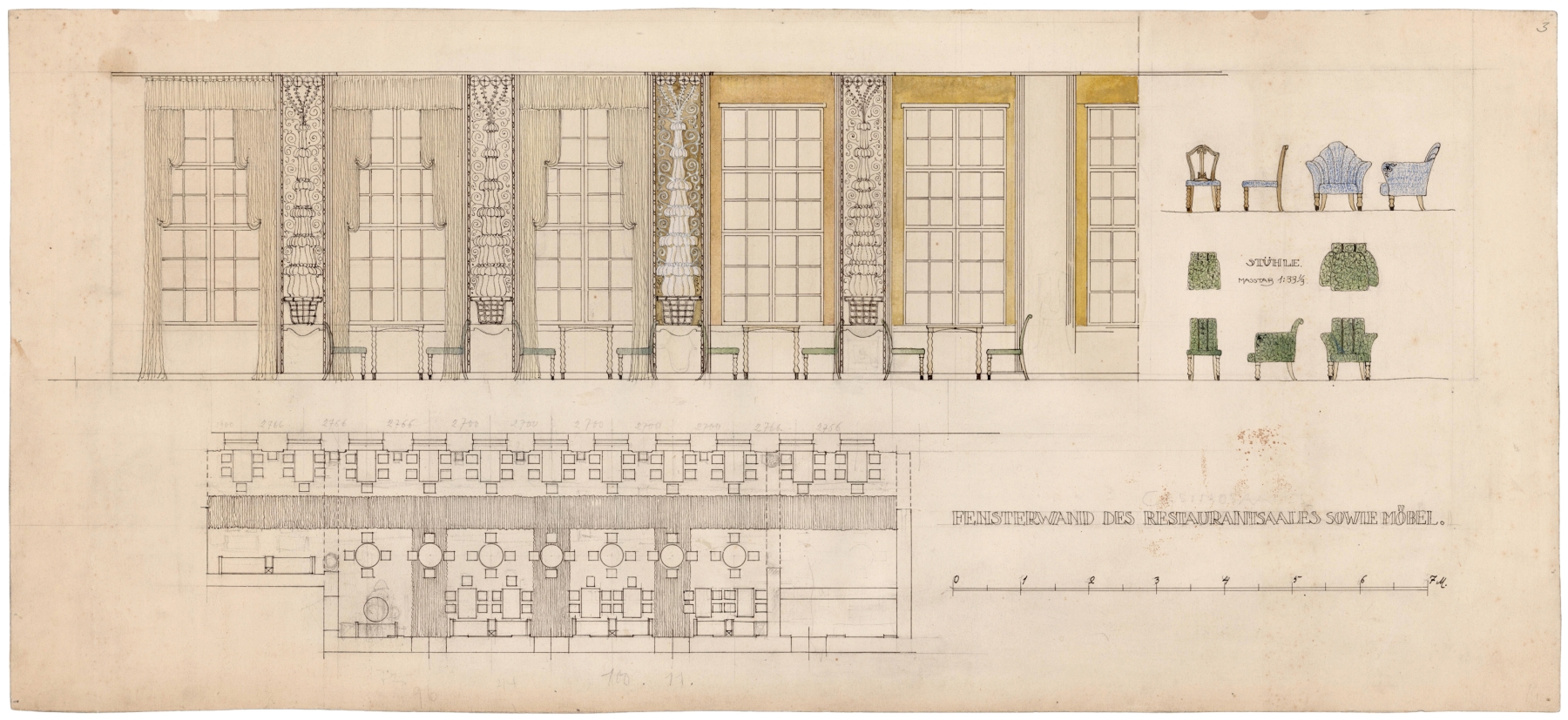

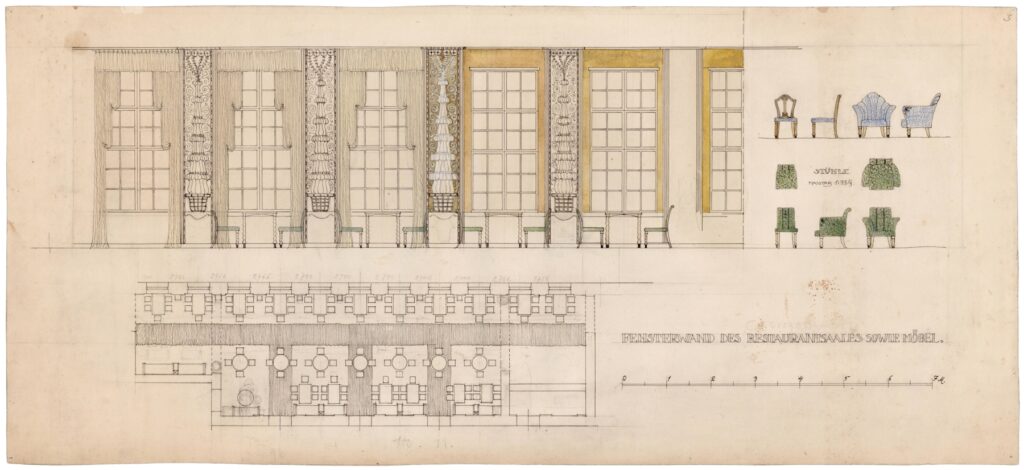

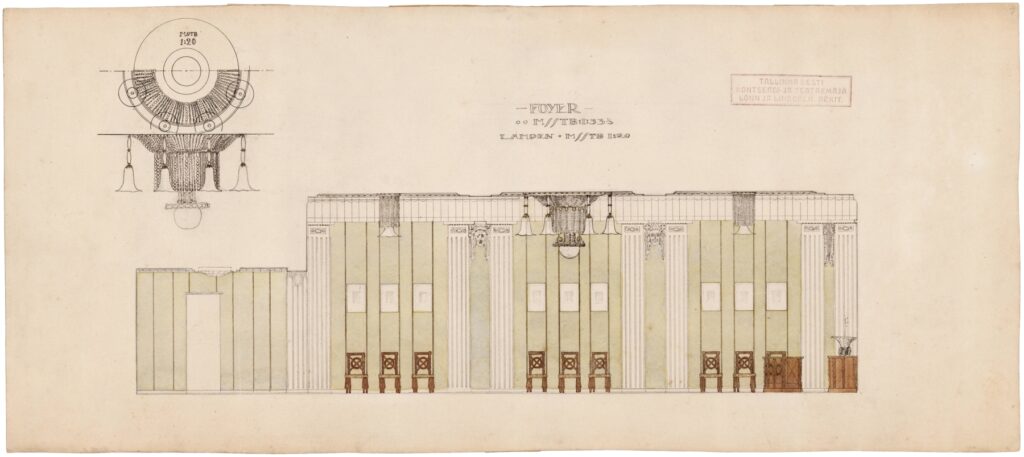

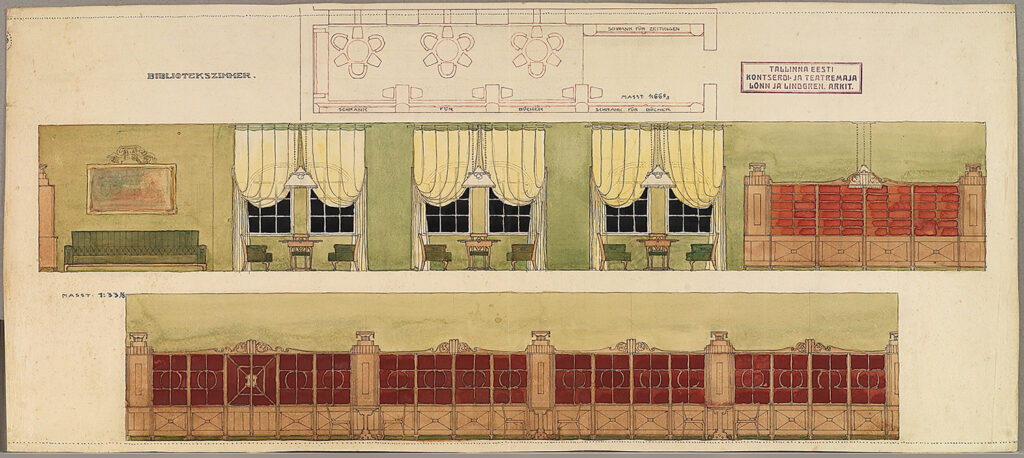

Interior design of the Estonia Theatre, 1911-1912

Armas Lindgren, Wivi Lönn, 1912. MEA 4.1.1

Interiors of the Estonia Theatre and Concert Hall

These watercolour drawings of an art-nouveau and classicist restaurant, library, and foyer were part of an entry package for the Estonia Theatre and Opera House’s architectural competition. The theatre building became a chief national symbol, a cultural citadel and one of the largest structures in Tallinn at the time. The foyers are adorned with mascarons; majestic chandeliers; and fashionable, fluted new-classicist pilasters, which were a novel phenomenon. Still, the final design of the national theatre’s foyer was slightly altered. The original theatre was destroyed in the March 1944 bombing of Tallinn, then restored according to a design by Alar Kotli (completed 1953), which replaced the original art-nouveau interiors with classicist Stalinist design. Drawings were acquired from the institution of “Eesti Ehitusmälestised” in 1993. Text: Sandra Mälk

-

-

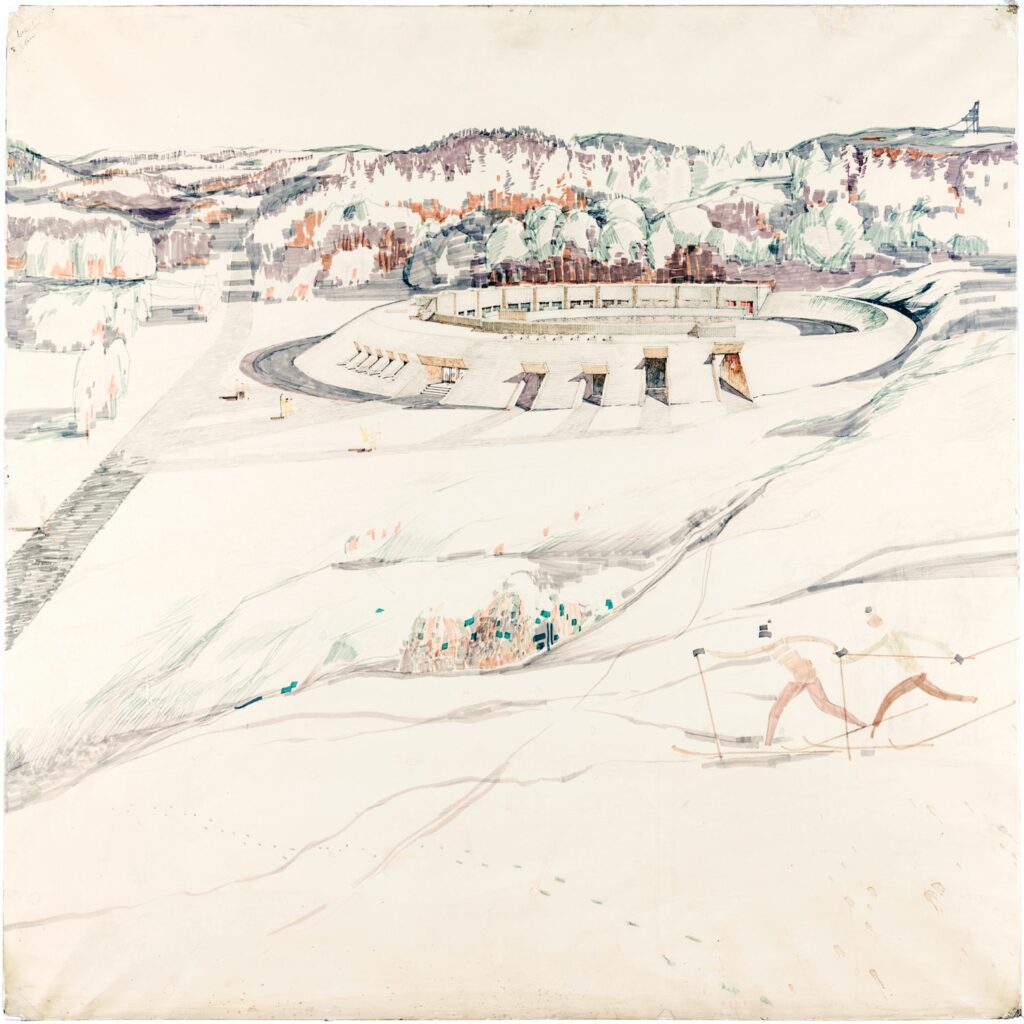

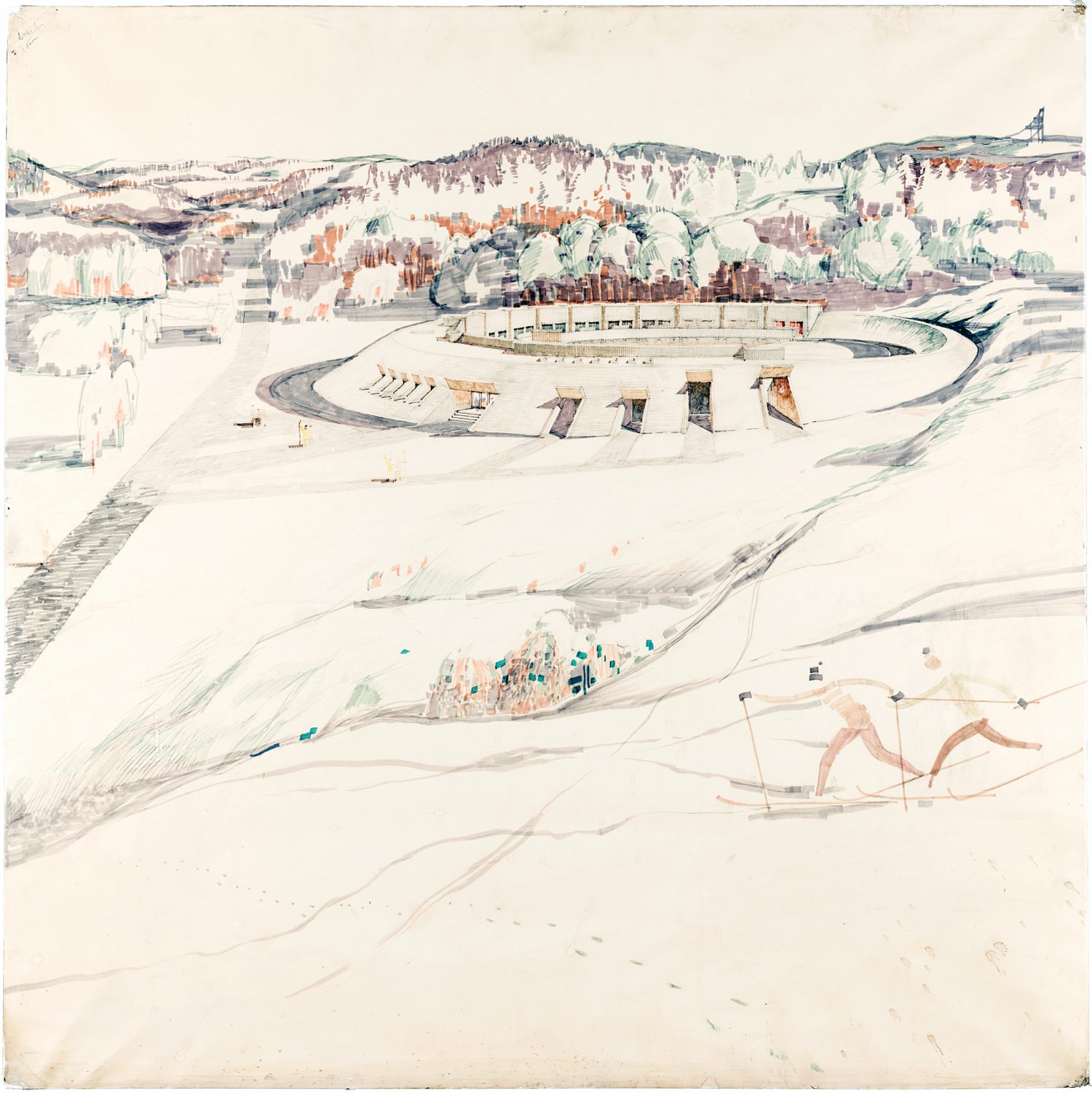

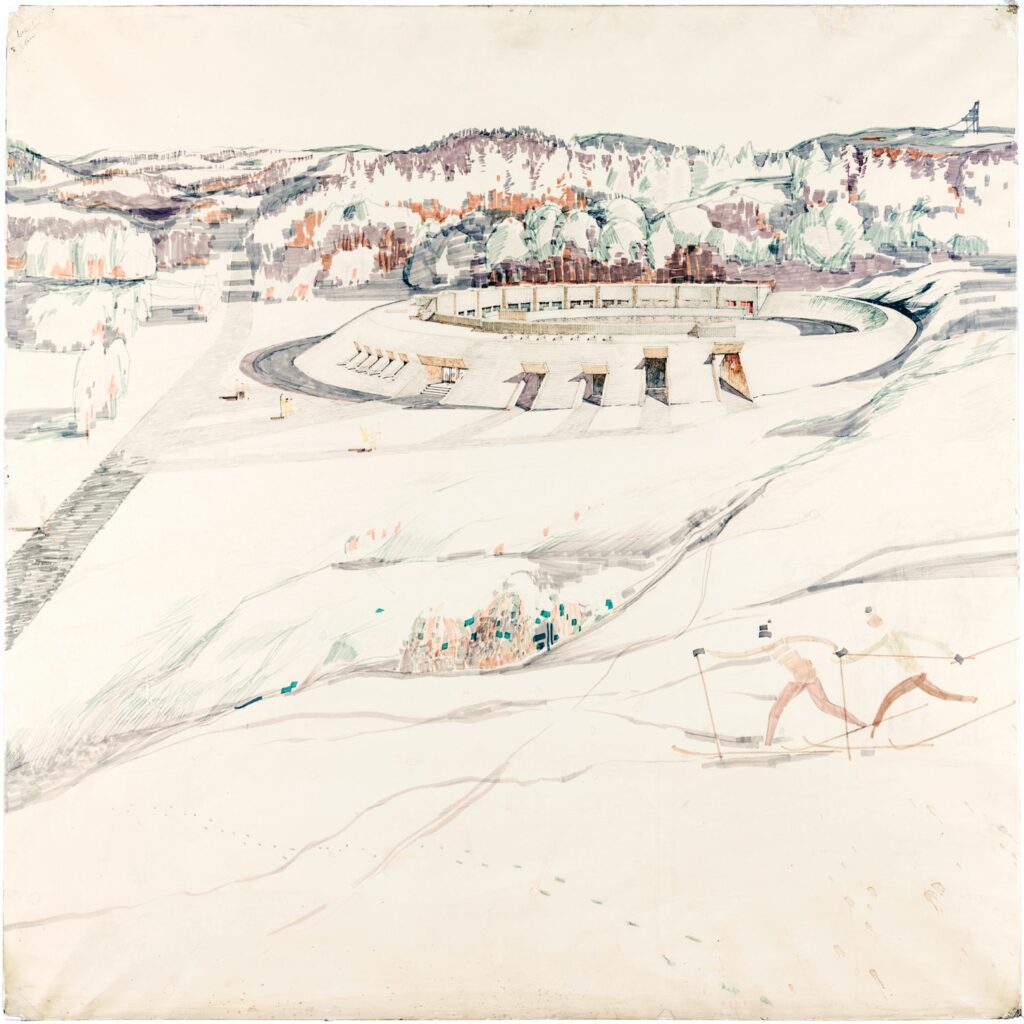

Tehvandi Ski Centre

Peep Jänes, Tõnu Mellik, Allan Murdmaa (drawing), 1974. MEA 4.6.2

Tehvandi Ski Centre

This modern ski centre was built in southern Estonia by commission of the State Committee for Sports of the USSR, and was intended foremost for training Soviet winter athletes. Its location in Tehvandi, on the fringes of Otepää (Estonia’s “winter capital”), was a proper choice, offering a wealth of athletic opportunities amid a landscape of rolling hills. The architects’ vision of a modern centre embedded in an artificial hill, sketched here in perspective, was realised to almost exact detail. Architects’ manner of approaching their task was location-based. Copying Otepää’s hilly landscape, they nestled another spherical form into nature. The Space Race also had a certain influence on the structure’s relatively technical form. The Union of Estonian Architects gave the watercolour to the museum in 1993. Text: Sandra Mälk