Valve Pormeister, design 1958, completed 1960. MEA 33.1.22

Flower Pavilion at Pirita Road in Tallinn

Architect Valve Pormeister, who graduated university in garden- and park design, claimed that nature was an intrinsic component of her, which was why she often put landscape first in her works. The Flower Pavilion melts into the landscape with a sensitivity characteristic of the architect’s signature. In addition to organic architecture, the building, which step-by-step ascends a hillside, also represents Finnish-influenced cornice architecture. This approach was rare and reviving (i.e. Nordic) in Soviet Estonian society at the time, as the rigidity of the early 1950s still echoed. The detail-rich interior sketches demonstrate the architect’s great enthusiasm for designing flower exhibitions – an activity she also practiced afterward. Text: Sandra Mälk

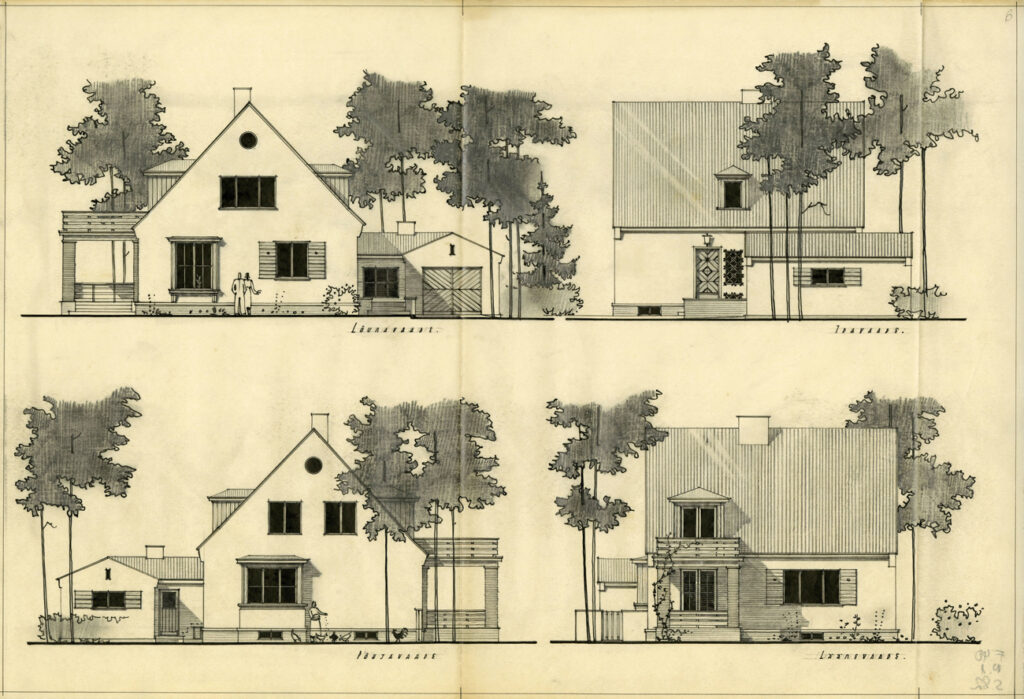

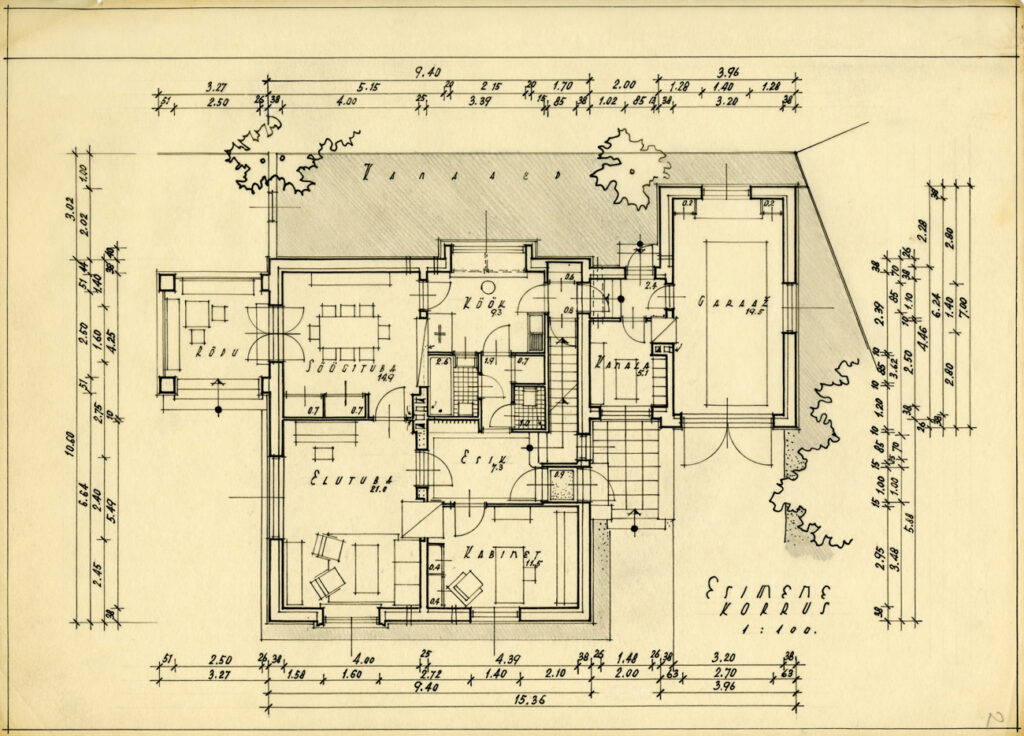

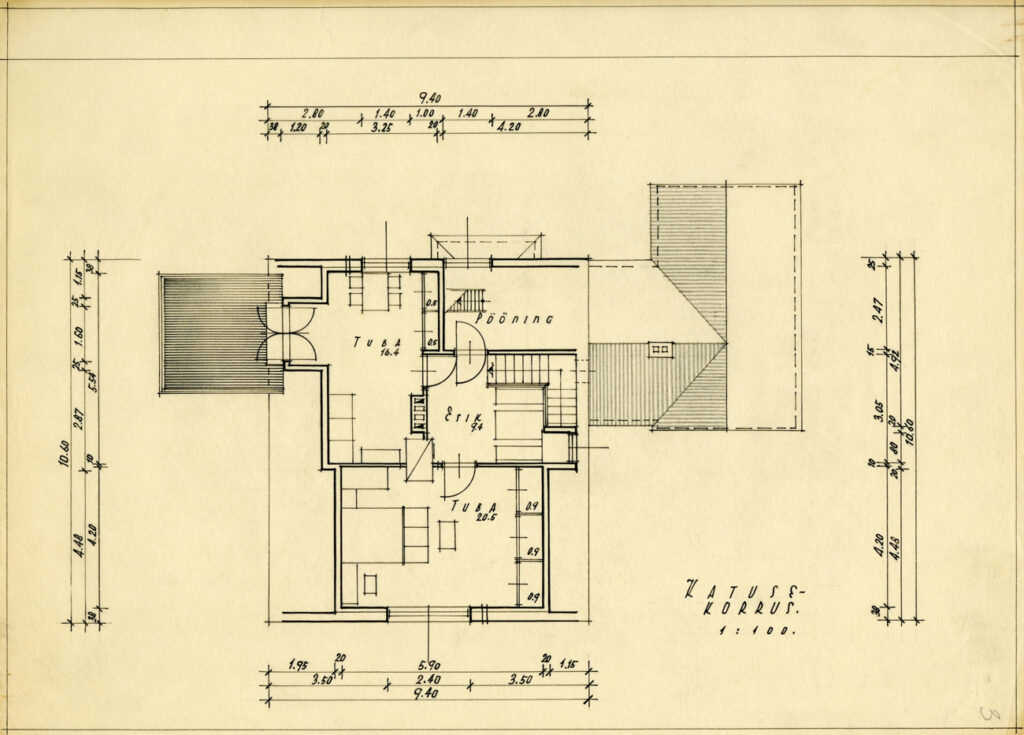

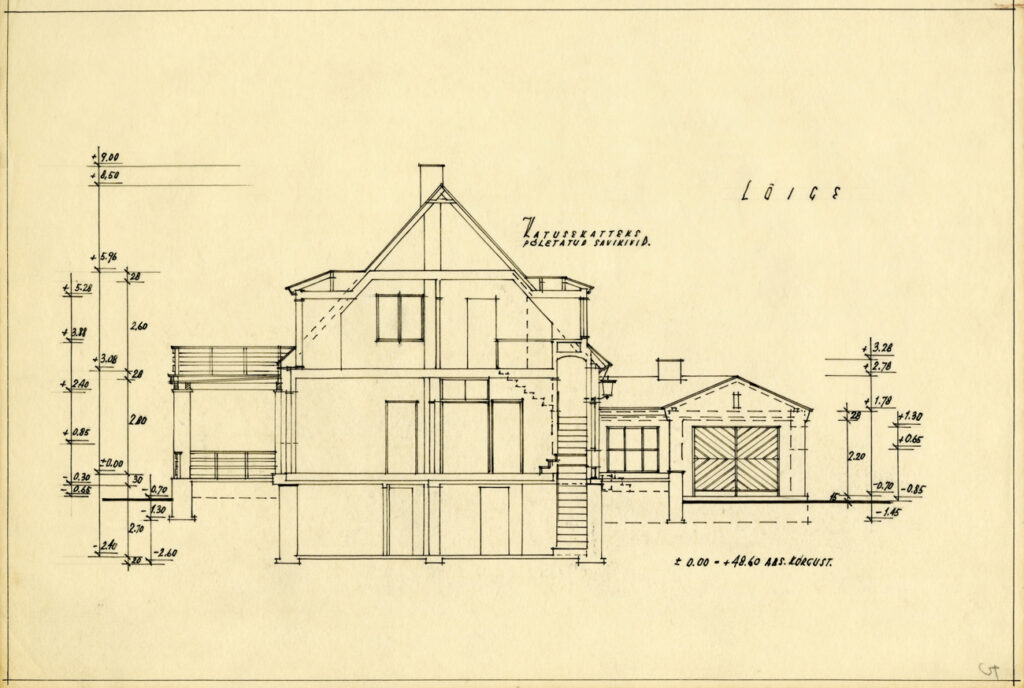

Peeter Tarvas, 1950s. MEA 40.1.82

Dwelling of family Kangur

There is a recognisable style to the dwellings erected in Estonia’s immediate post-war years. These stone buildings with tall gabled roofs and raised gutter-lines can be found all across the country. Their construction derives from traditional German heimat architecture, intended to give residents a cosy sense of home with the help of small elements such as romantic shutters. The style also pleased the Stalinist regime: it was sufficiently unlike the dominant pre-war flat-roofed structures, which carried “unfit” Western European values. The project was donated to the museum by Maria Tarvas along with many materials from the family collection in 2006.

August Volberg, Heili Volberg, 1958. EAM 31.1.37

Writers’ House

The Writers’ House in Tallinn old town was opened in the spring of 1963. The project of the four-storey building was designed by the architects August and Heili Volberg at the national design institute “Estonprojekt” in 1958. The seemingly laconic Writers’ House is characterized by the rationality typical of modernism. The regularly spaced windows indicate the different functions of the building – spaces for public use are located behind the large windows, private living spaces are hidden behind the smaller three-part windows. The building is connected to the historical architectural environment by a high pitched roof that fits the rooftop landscape of the old town. On the ground floor next to Harju Street, there was a book store called “Lugemisvara” with large display windows. On the corner of Harju and Vana-Posti streets, the cafe “Pegasus” with a modern interior design is located on three floors. A vestibule with a wardrobe and auxiliary rooms were originally planned in the first floor. On the next two floors are the halls of the cafe, the windows of which offer a view of St. Nicholas Church, the verdant green area and the Eduard Vilde monument. The floors of the cafe are connected by a spiral staircase. The premises of the Estonian Writers’ Union and a 150-seat meeting hall with an expressive black ceiling are located in the three-storey part of the building facing Kuninga Street. There was also space for the editors of the “Looming” magazine and the Literary Fund. In addition to the public function, two to five room apartments for writers and their families were planned in the building. In the larger apartments, one room was planned as a writer’s workspace. During the later reconstruction, the fifth floor of the house, under the roof, was built. Text: Anna-Liiza Izbaš

(klick on the picture to see more illustrations)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

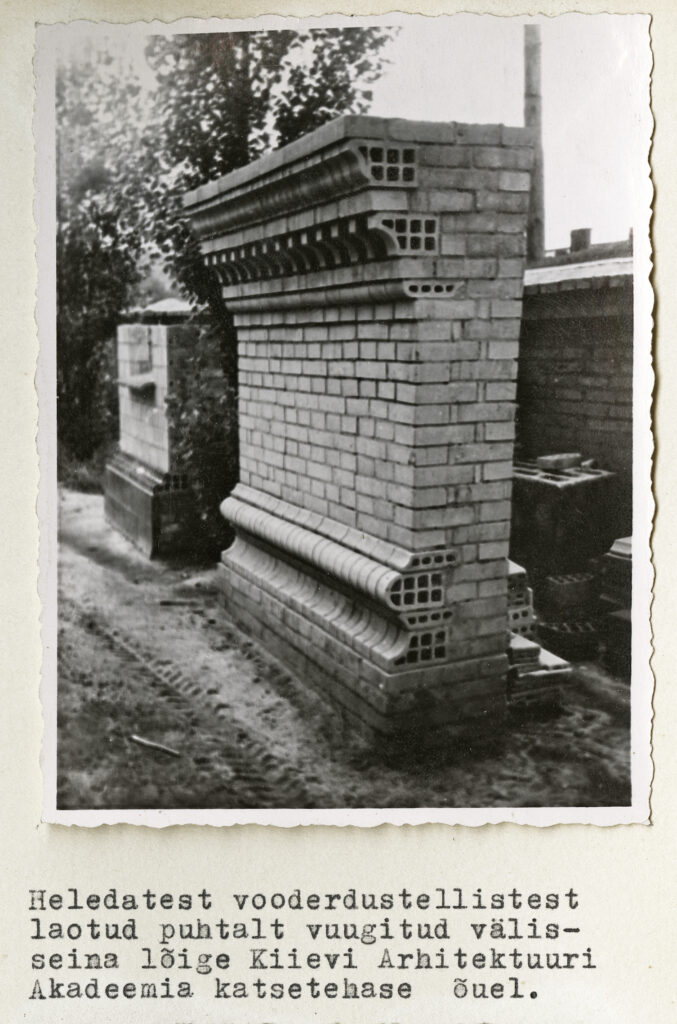

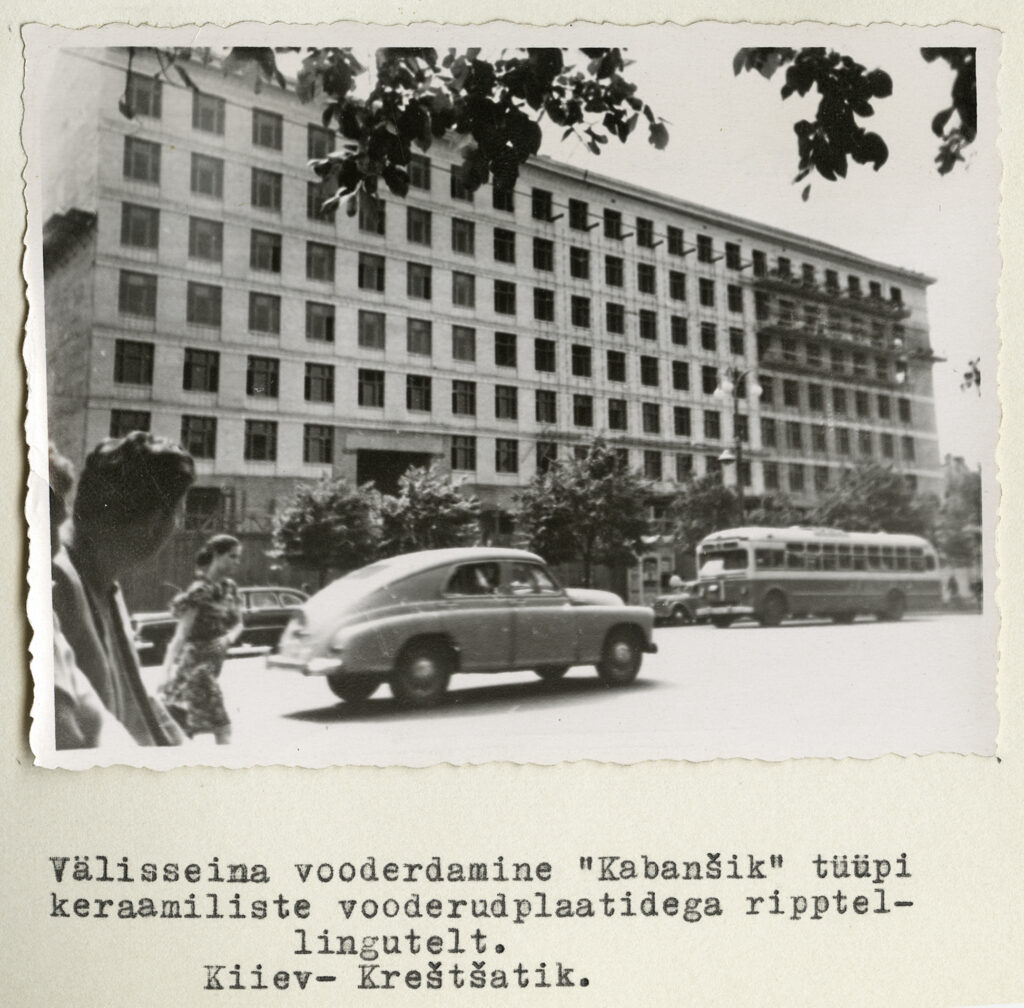

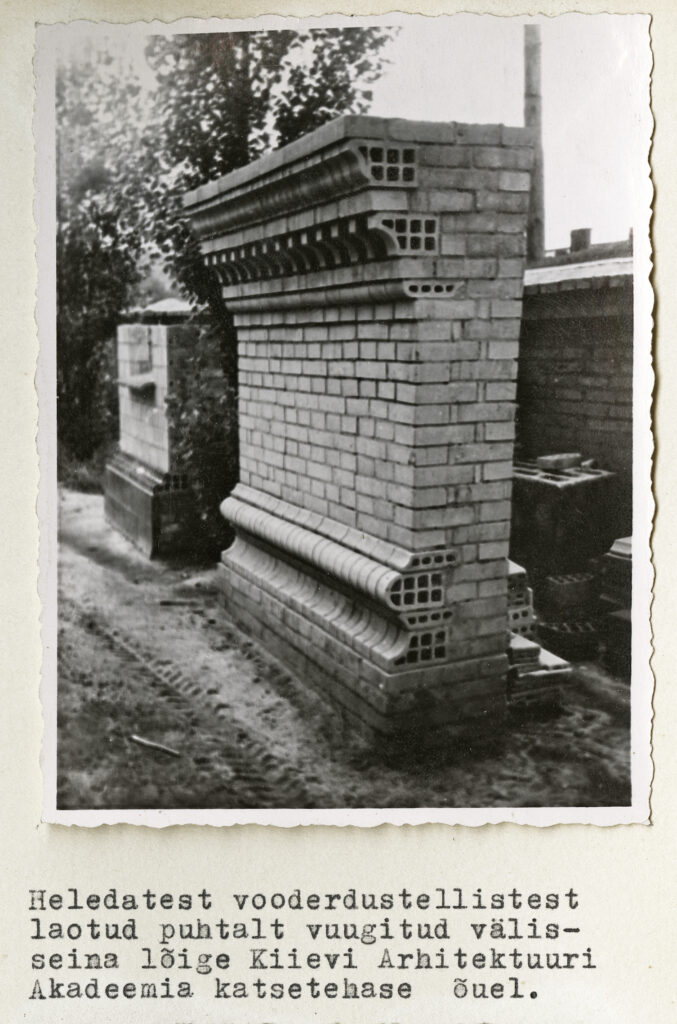

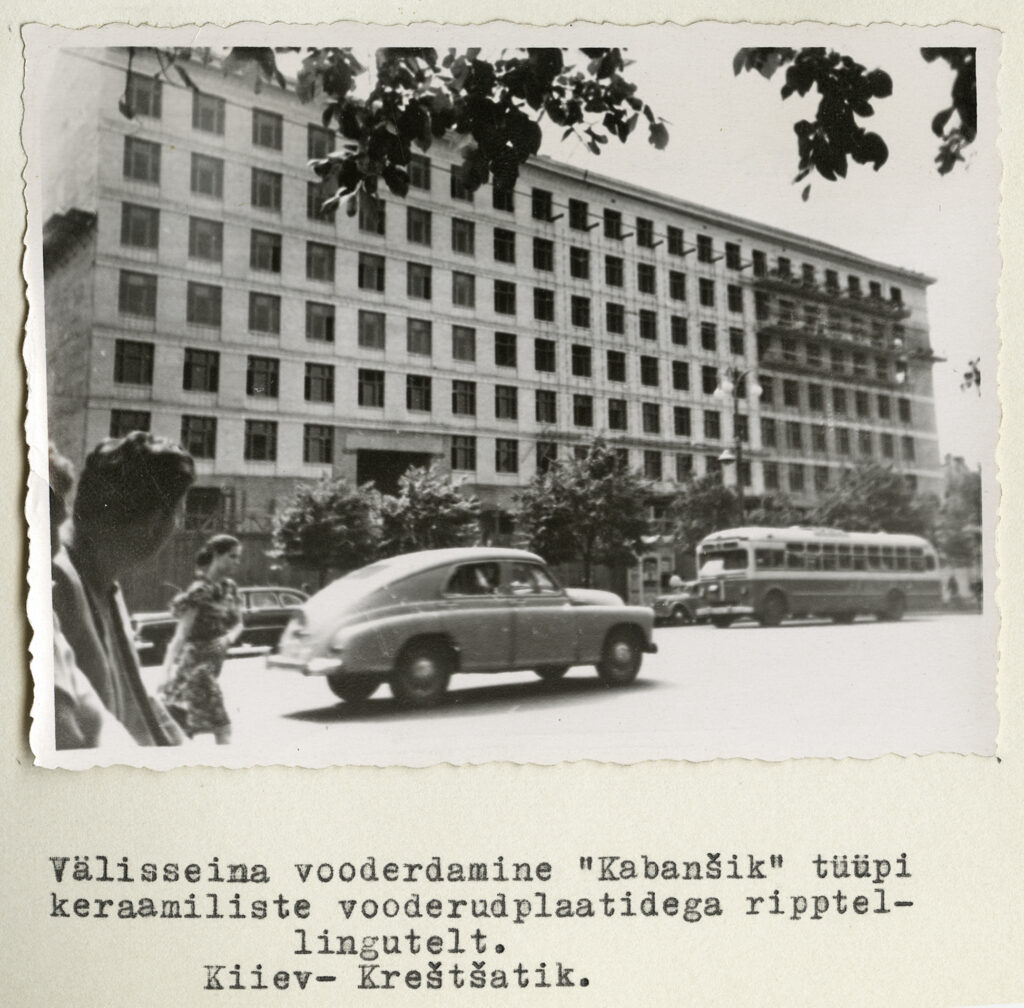

Installation of facade tiles along the Khreschatyk street in Kiev

Mart Port, 1956. EAM 10.4.12

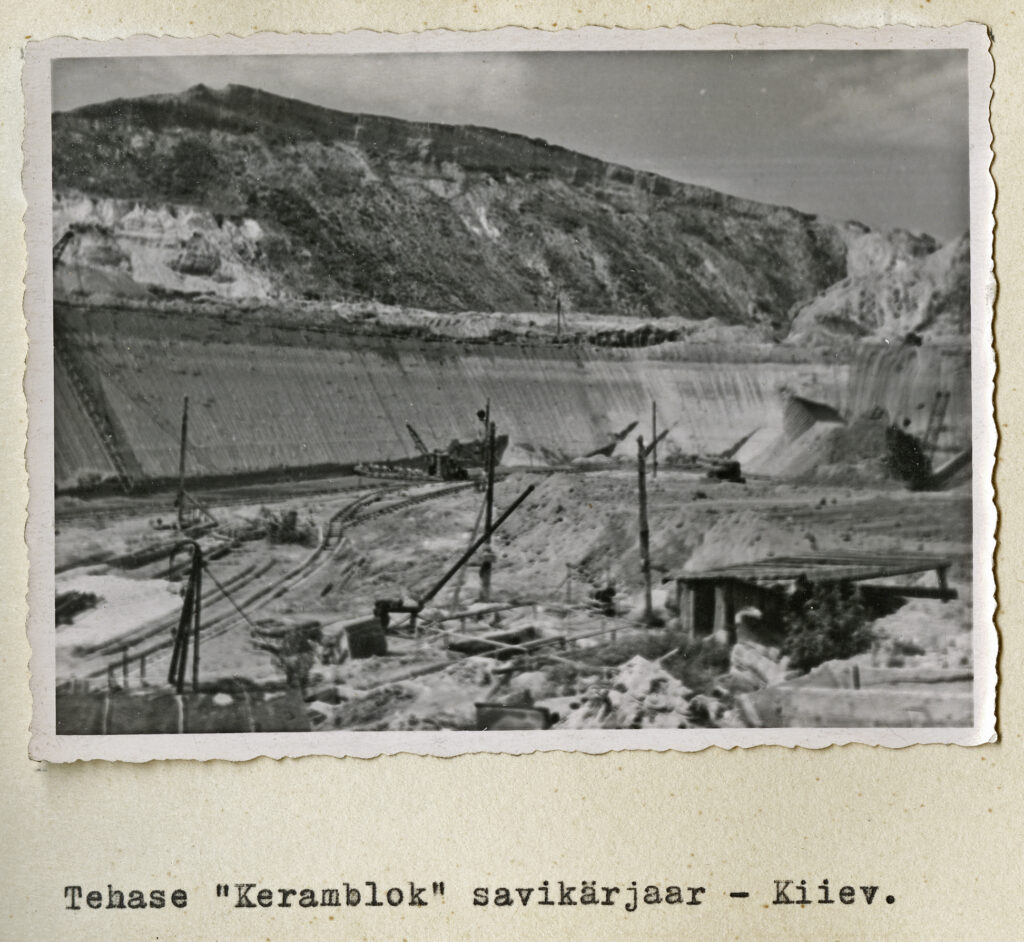

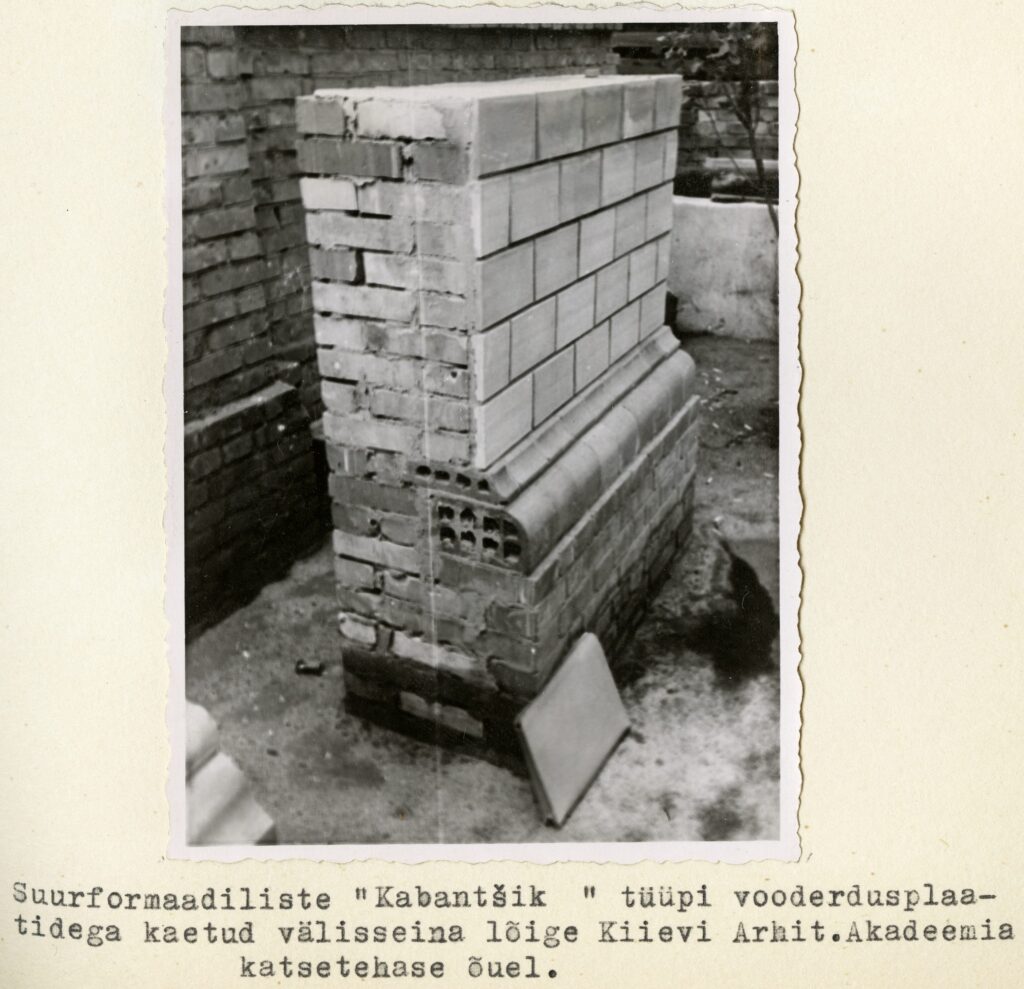

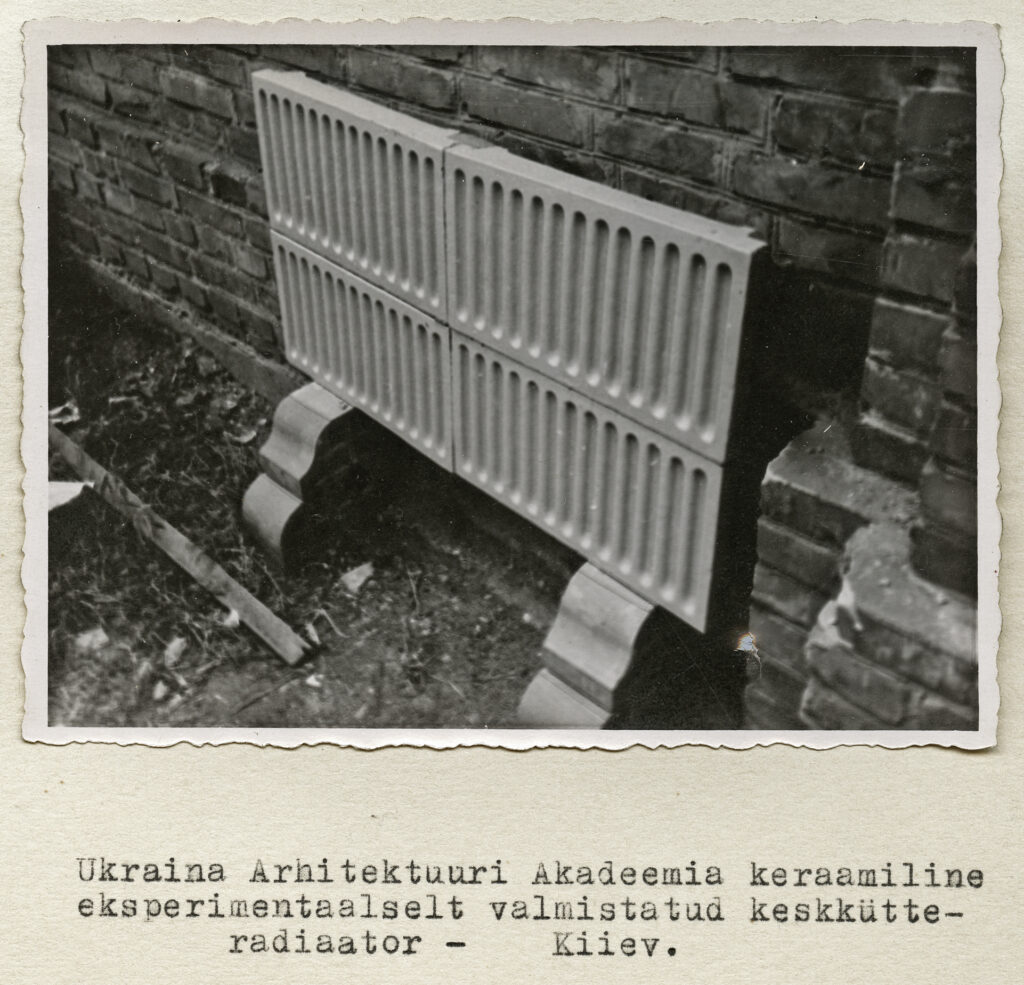

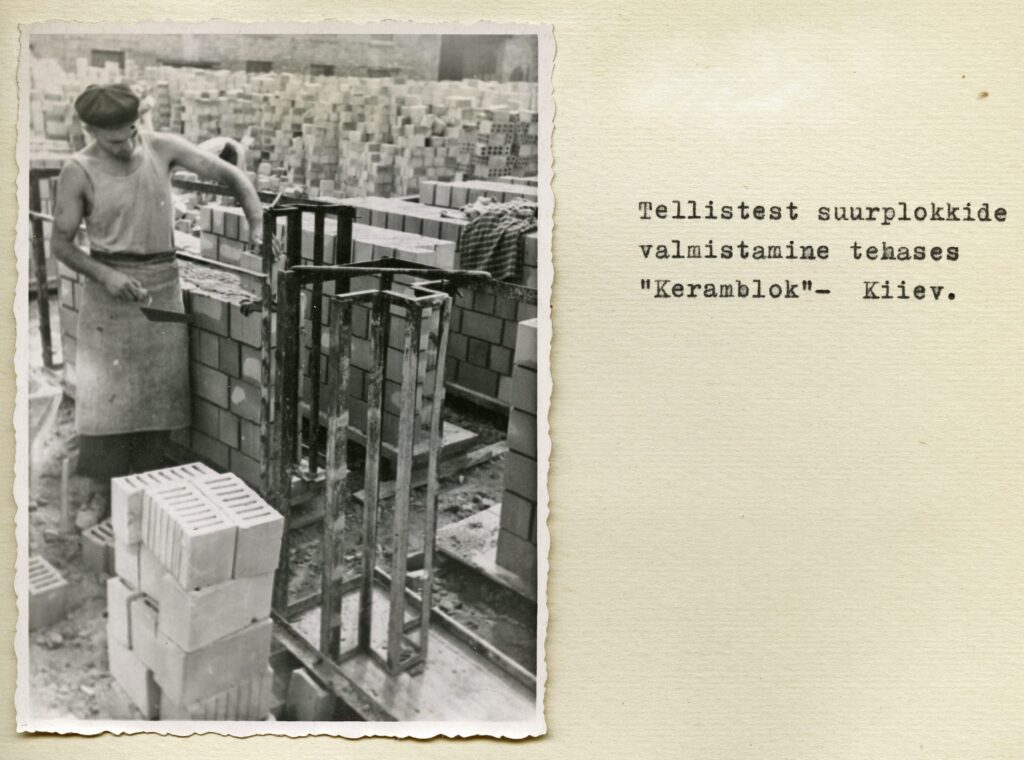

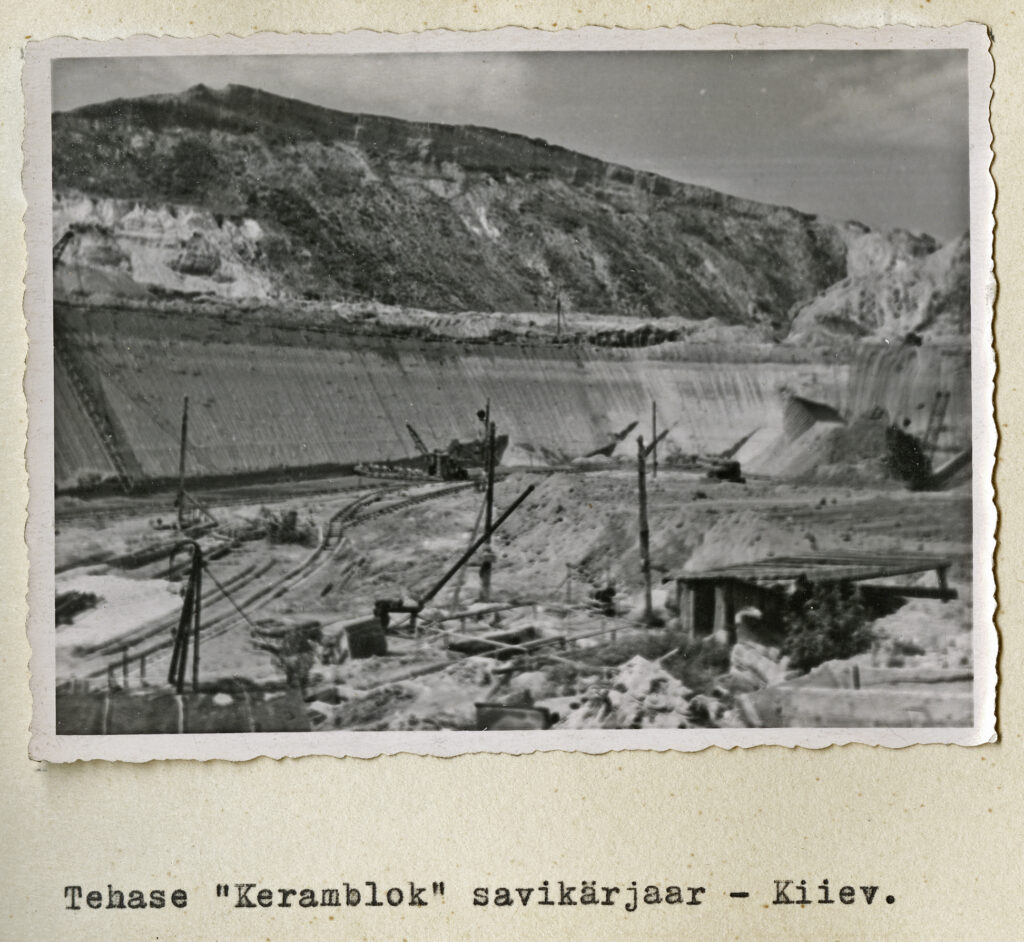

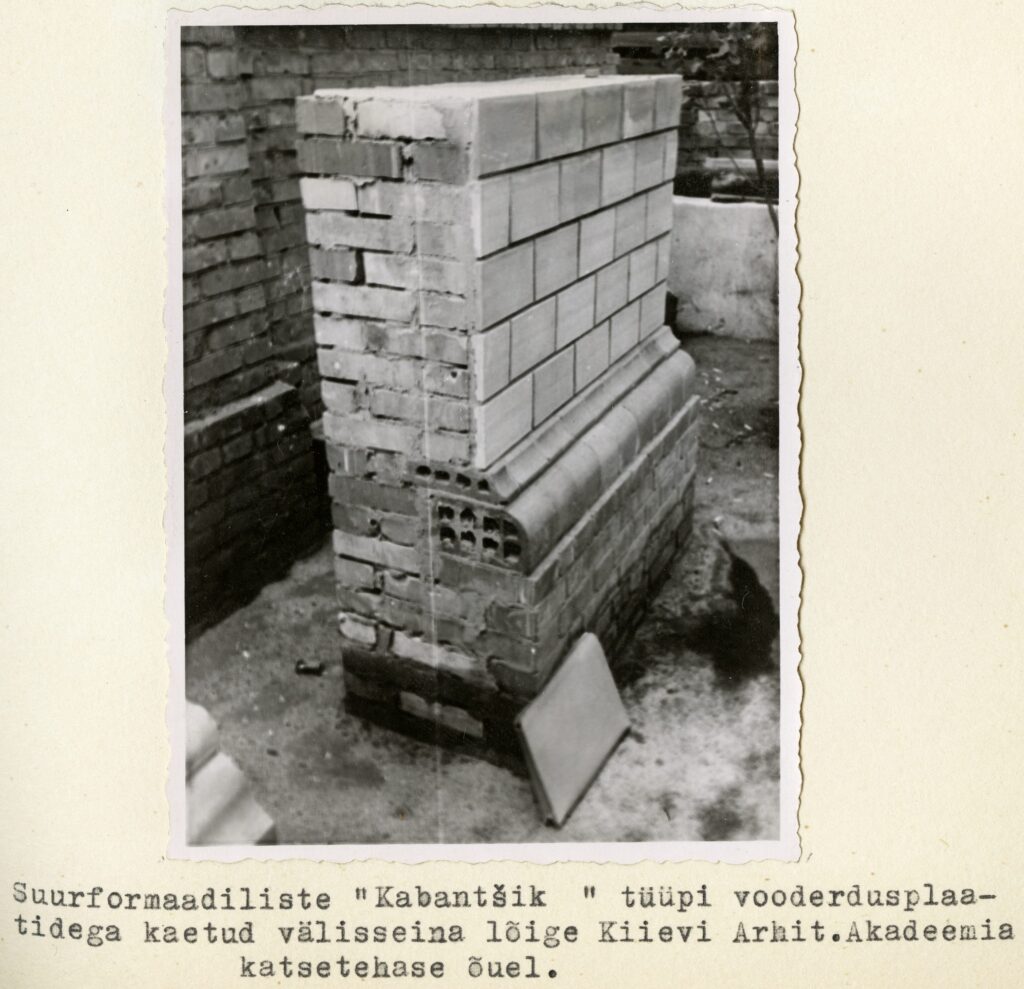

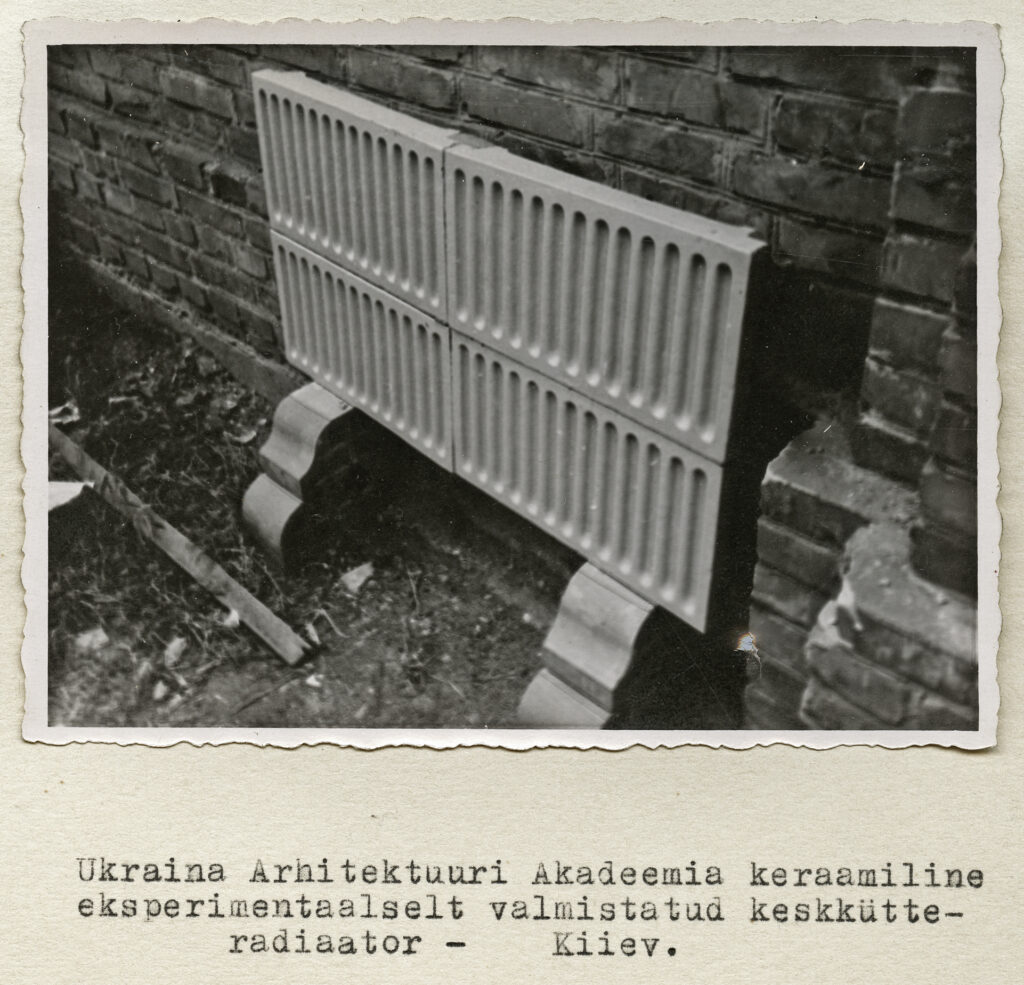

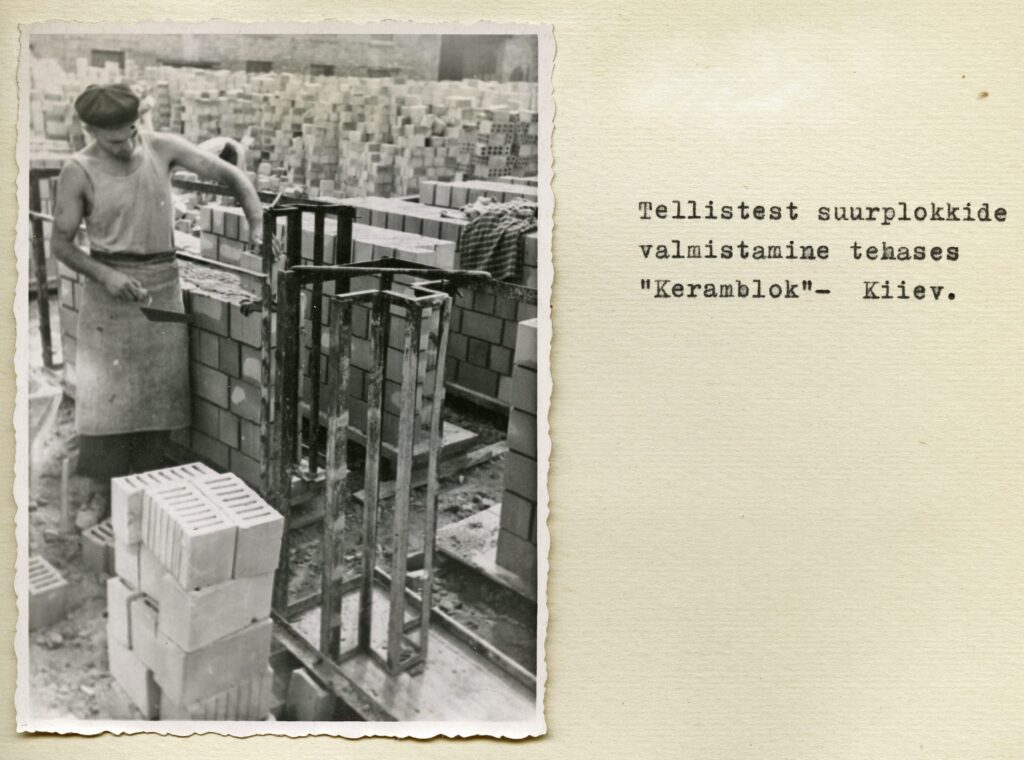

Visit to the Building Ceramics’ Factories in Kyiv

The aim of Mart Port’s creative business trip (1956) was to study whether it would be possible to increase the quality and speed of industrial construction in the field of intensified mass housing construction. During the month-long trip, he passed various cities on his way from Tallinn to Ukraine and back: Riga, Kaunas, Vilnius, Lviv, Ushgorod, Kyiv. In the report of the business trip, the architect concludes that in Latvia and Lithuania, for example, the construction methods related to the construction of mass housing are quite similar here, but the tiles used for the exterior façades, which were produced in Kyiv, deserve special attention. From there he took detailed pictures for the report. He was particularly impressed by the lining of local clay tiles of the “Kabanchyk” type, developed at the Kyiv Academy of Architecture. The “kabanchyks” were light tiles, partly hollow, which were installed on the wall using small and hanging scaffoldings. The architect already knew that in Estonia it is possible to obtain the white clay needed for its production from the Joosu quarry in Võru County. During the trip, he visited the Keramik and Keramblok ceramic tile factories and the red clay mine of the latter. The Ukrainians, who have a long tradition in the clay industry and building ceramics, also introduced him to a experimental ceramics plant under construction at the Kiev Academy of Architecture, where new prototypes used in construction were completed. In the report, he pointed out that knowledge was shared bilaterally. The builders of Kyiv, Minsk, Vilnius and Riga had got acquainted with the method of covering the walls with granite plaster used in Tallinn and praised the innovativeness of this method. Text: Sandra Mälk

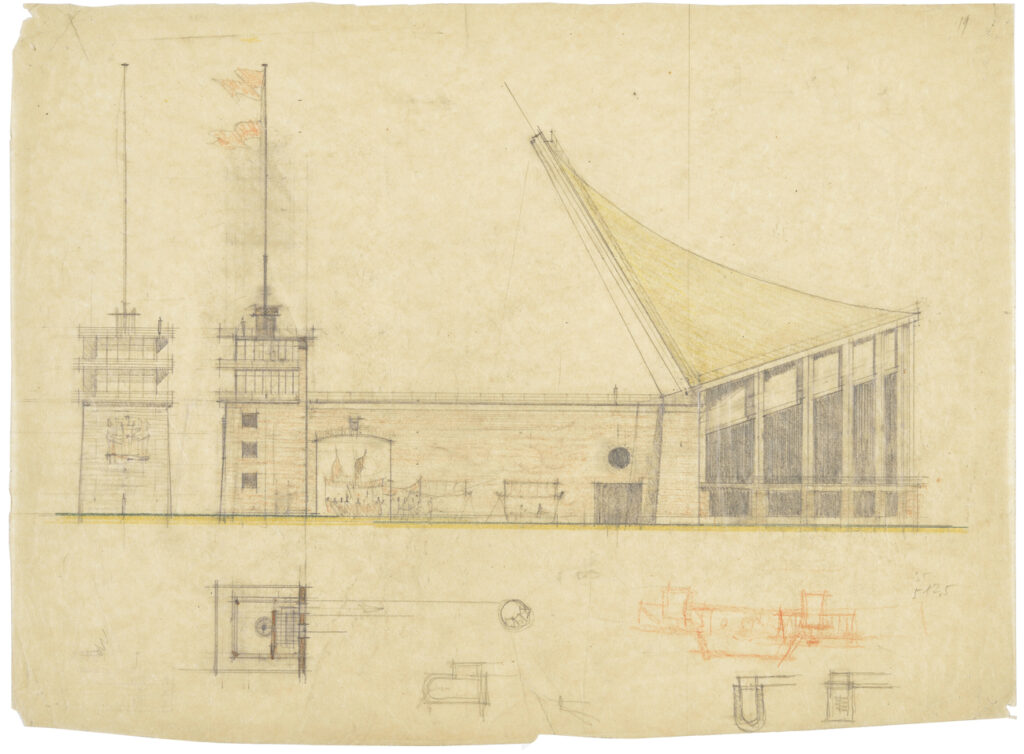

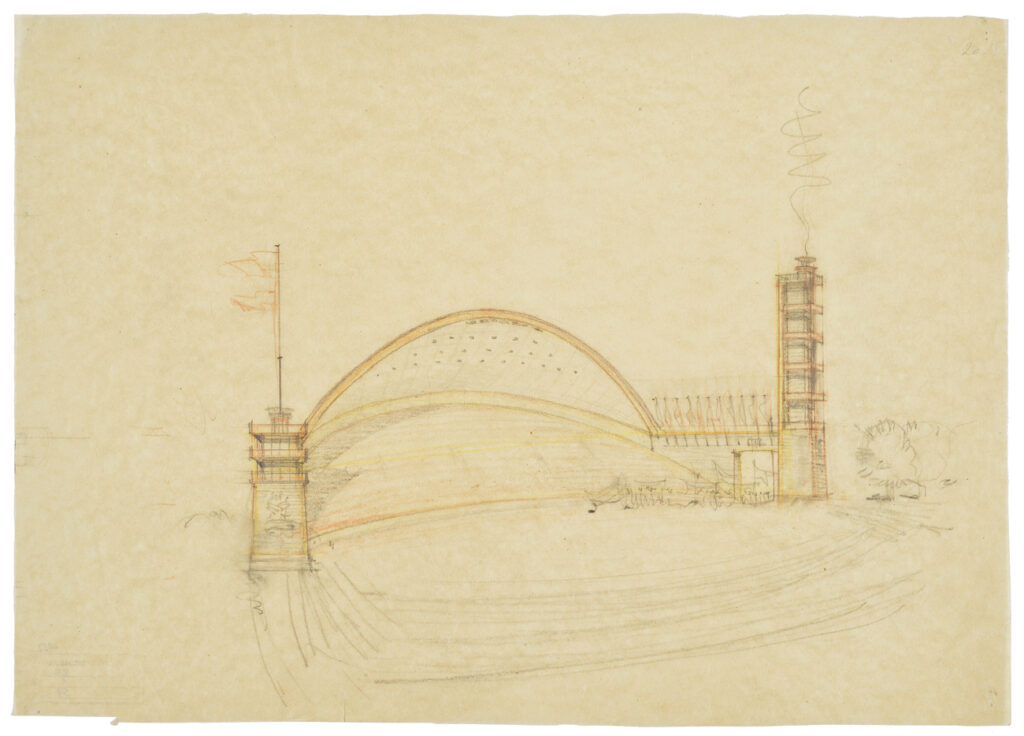

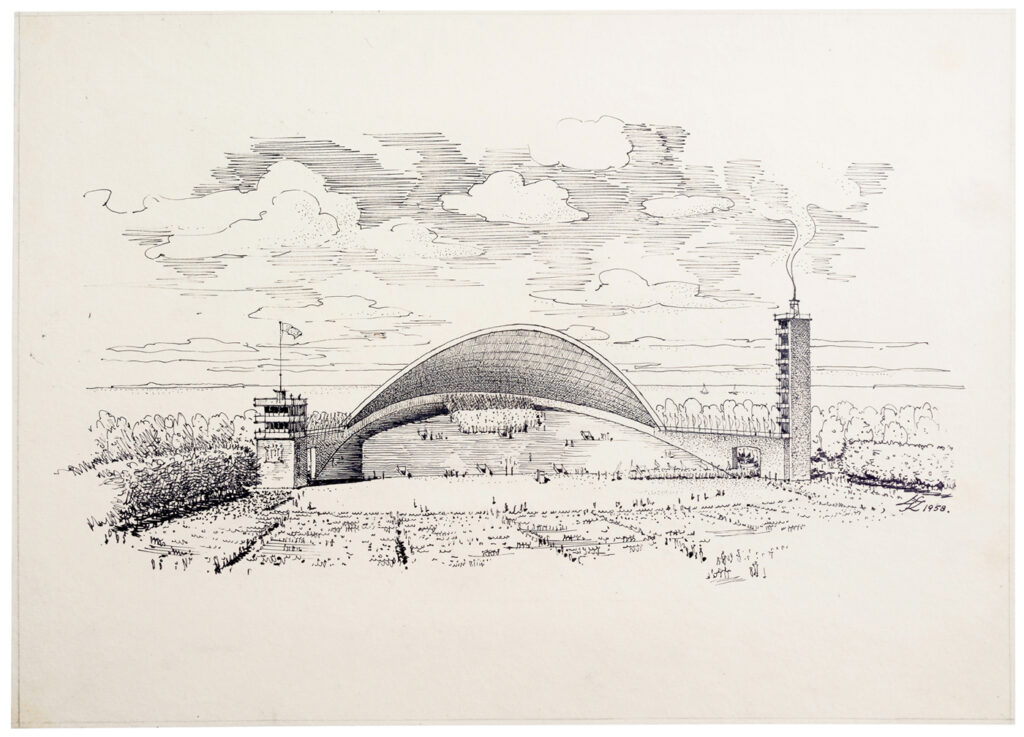

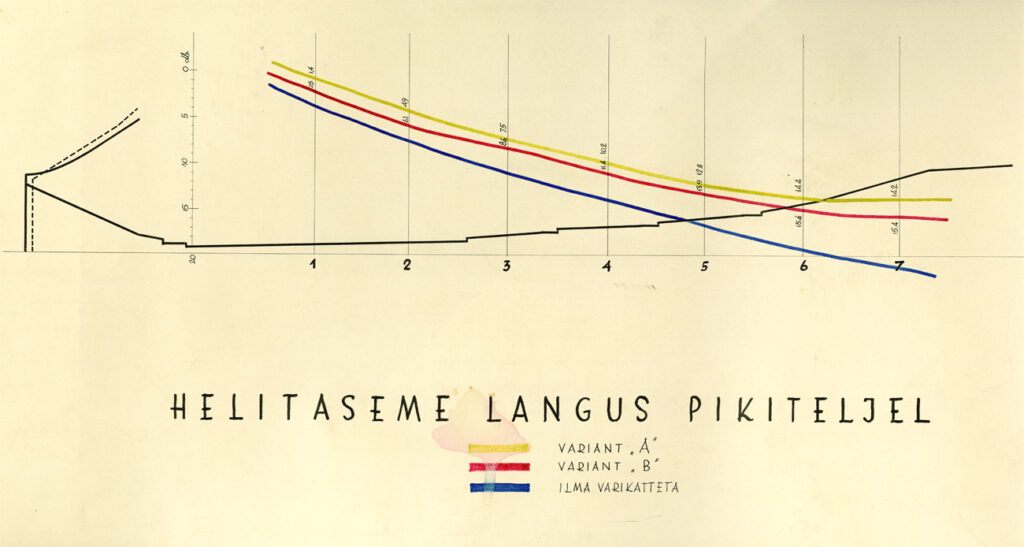

Alar Kotli, 1957-1958. MEA 23.1.51

Tallinn Song Festival Arena (sketch)

The Tallinn Song Festival Arena represents the re-arrival of modernism to Estonia during the Khrushchev Thaw. The Estonian SSR leadership commissioned the structure to mark the 20th anniversary of Soviet rule, but to Estonians, it was a symbol of their nationality and culture. The Song Festival Arena was essentially also a way of the nation thumbing its nose at the USSR – with its completion, Estonians’ nearly 100-year tradition of holding mass song festivals was immortalised. Alar Kotli came close to an entirely innovative final solution already when making his initial sketches, which include a saddle-roof in the shape of a hyperbolic paraboloid that functions as an acoustic screen. The sketches were donated to the museum by Anu Kotli in 1997. Text: Sandra Mälk