Tag Archives: Tallinn

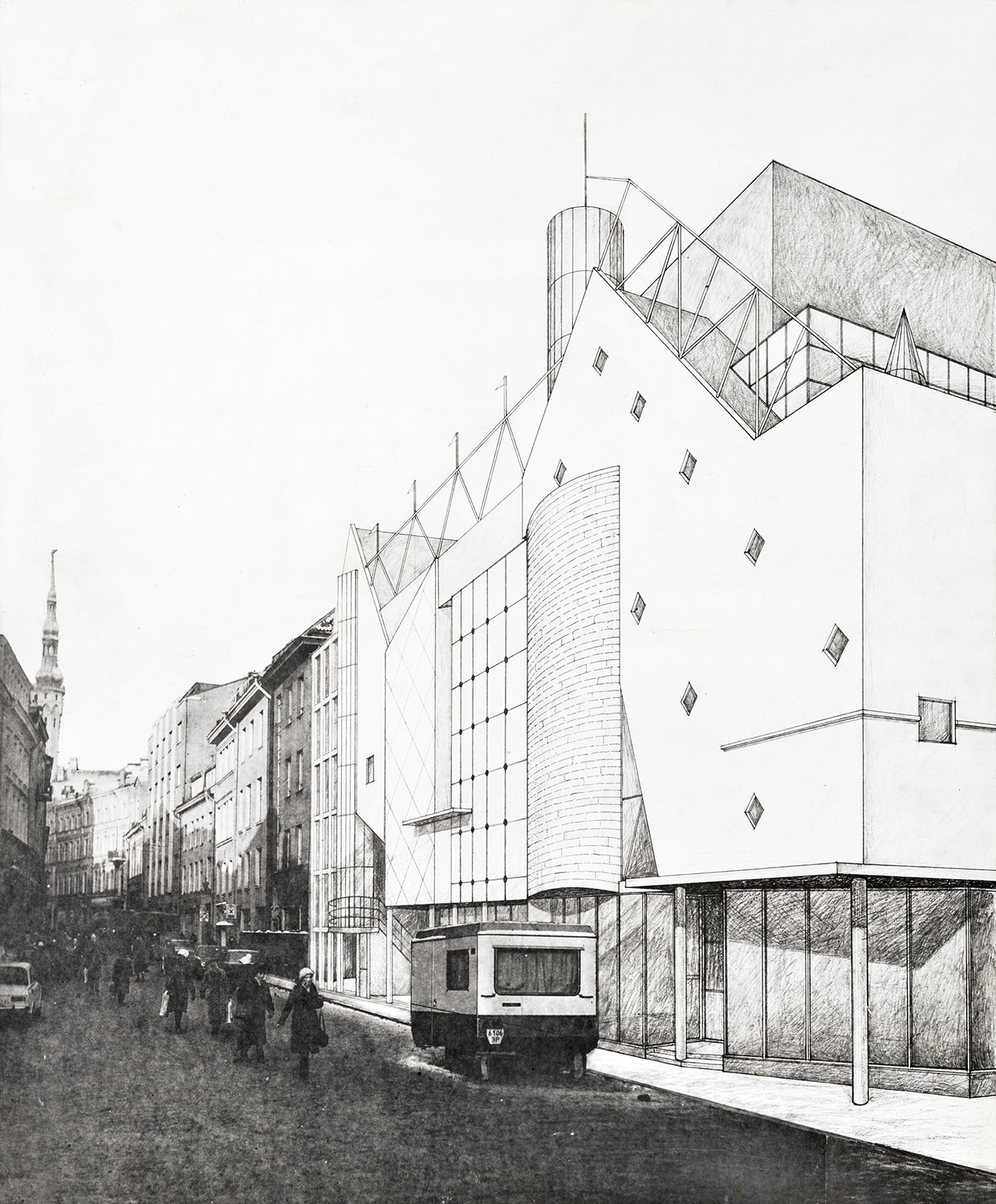

Vanalinnastuudio theatre building in Tallinn

Vilen Künnapu, Ain Padrik, 1987. EAM 41.1.16

Comedy theatre Vanalinnastuudio, which started out in Tallinn Teachers’ House, became so popular under the leadership of the legendary theatre director Eino Baskin that in the mid-1980s there was an idea of building the theatre its own house in the Old Town. The beginning of Viru Street had a plot that had long been vacant (currently the De la Gardie shopping centre, 1999) and it was considered as one possible location for the building. The theatre house was designed as a black box theatre with seats for 200 people and an attic storey for lowering decorations to the stage below. The postmodernist building was never constructed under the new political regime. The display board together with the section and view was given to the museum in 2005 by architectural historian Liivi Künnapu. In addition to that, last year the architecture office Künnapu&Padrik donated their drawings and digital archive to the museum. The lot, consisting almost 200 projects, is in the final process of adding to the musem’s collection. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1980s, architect: Ain Padrik, architect: Vilen Künnapu, Tallinn

Seaside park in Tallinn

Lidia Pettai, 1961. EAM 15.4.150

60 years ago, the opening of the Tallinn sea border was under discussion with the intention of turning it into a green area with port facilities. Back then, In the 1960s, and primarily at Finland’s initiative, plans were made to clear up all the areas surrounding the port with regard to the reopening of the Tallinn-Helsinki seaway and the construction of the passenger port. The seaside area – in the immediate proximity of Old Town – was partly in the military zone and opening it up to the city became a lively issue. Although, only a handful of buildings were fixed up during the Soviet era. New buildings were due to be constructed in the densely built-up industrial area together with the main park road that was in the direction of Mere Boulevard (No. 1), such as the beach café (7), the port building (3) and children’s playgrounds (8). A team of architects worked with the design at the Eesti Tööstusprojekt. Kalju Vanaselja designed the buildings and H. Parmasto behind the schemes of coastal reinforcements. The plan was designed by architect Lidia Pettai, whose watercoloured work was given to the museum in 2012 by Reet Priilaht. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1960s, architect: Lidia Pettai, Tallinn

Office and Residential Building at Pärnu Road

Eugen Sacharias, 1936. EAM 2.2.320

The seven-storey building on the corner of Pärnu Road and Väike-Karja Street is one of the most representative rental houses built in the second half of the 1930s in the center of Tallinn. The project was commissioned from Eugen Sacharias (1906–2002) by the association “Elamu”. On the ground floor there were and still are business premises, on the first floor offices and on the higher floors there were multi-room apartments with all amenities, bathrooms and maid’s rooms. As there were several doctors among the tenants at that time, this house has also been called the so-called doctors’ house. On the seventh floor of the building were the offices of the architect Sacharias.

The Baltic-German architect Eugen Sacharias was born on April 21, 1906, who studied at the Technical University of Prague in 1925–1931. As a talented and enterprising young architect, he first helped Eugen Habermann design the so-called Urla House on 10 Pärnu Road, after which he founded his own office. In the following ten years almost 40 apartment building projects were completed. That shaped the representative visual of Tallinn as the capital. In 1941, Sacharias left to Germany with his family and ended up in Australia, where he continued to work as an architect in a construction company. In April 1991, Eugen Sacharias’ 85th birthday was celebrated with an exhibition in the lobby of the Library of the Academy of Sciences (now the Tallinn University Library). The exhibition was curated by art historian Mart Kalm. This was the first exhibition of the Estonian Museum of Architecture, founded three months earlier.

Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1930s, architect: Eugen Sacharias, Tallinn

EMA 30 / Tiny tour of models: Extension to Tallinn Secondary School of Science

Marika Lõoke, 1981. MK 227

Tallinn Secondary School of Science (Tallinna Reaalkool) will be 140 years old this year. The school was founded in 1881, in the same year an all-Russian architectural competition was organized to obtain a schoolhouse project. The competition was won by Max Hoeppener (1848–1924), a Baltic German architect from Moscow. Hoeppener was assisted in the construction project by Carl Gustav Jacoby, a Tallinn city engineer at the time. The first building designed for a school building in Tallinn was completed in 1884.

A century later, in 1981, a competition was held for a vision of the extension of the school building. The location of the new addition was to be set on the current sports field. 13 works came to the competition. The first prize was given to the architects Vilen Künnapu and Ain Padrik for the project named “Kivirünta” (EAM 41.1.10), the second place went to Kullervo Kliimand’s work “Poiss” (“A Boy”). The third prize was shared by Kiira Soosaar, Siiri Kasemets and Jüri Karu’s competition work “Imelik” (“Strange”) and “Koolimaja” (“School House) by Marika Lõoke. In the magazine Ehituskunst, the editor of the magazine, architect Ado Eigi, describes it as follows: “ In addition to the attractively playful, postmodernist façades maintained at a good professional level and the expressive plan solution, the competition work “Koolimaja” (author Marika Lõoke) also suggested an interesting corner solution together with the M. Gorky named Library building (now Tallinn Central Library – A.L.).” A year later Marika Lõoke also received the 3rd prize at the competition for the new building of the Kreutzwald State Library. The library competition model belonging to the collection of the Museum of Architecture can be seen in the soon-to-open exhibition at the National Library. Together with several other models, the author donated them to the museum in 2017. See also “Architecture. Second-third, 1982–1983.” Text: Anne Lass

Veel: 1980s, architect: Marika Lõoke, Tallinn

Linnahall Square and the Merepargi Taimelinn (the Plant City of the Sea Park)

Ignar Fjuk, 1982. EAM 5.4.61

Tallinn Linnahall was built during the building frenzy which preceded the 1980 Olympics, but the surroundings were not developed as planned. The area between the power station and the commercial port was cleaned of the production residue from the factories and the concrete blocks that were laying around. At the same time, discussions became louder about granting people in the city access to the coastal zone, which had thus far belonged to the border zone and been managed by large factories. Ignar Fjuk designed a green park area to surround the Linnahall, which also included a place for architectural forms – gates and pavilions. He presented his vision in the group exhibition ofthe Tallinn School, which took place at the Tallinn Art Salon in 1983. This illustration made in ink and gouache was given to the museum as a gift by the author in 2002. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1980s, architect: Ignar Fjuk, Tallinn

A new environment of Tallinn

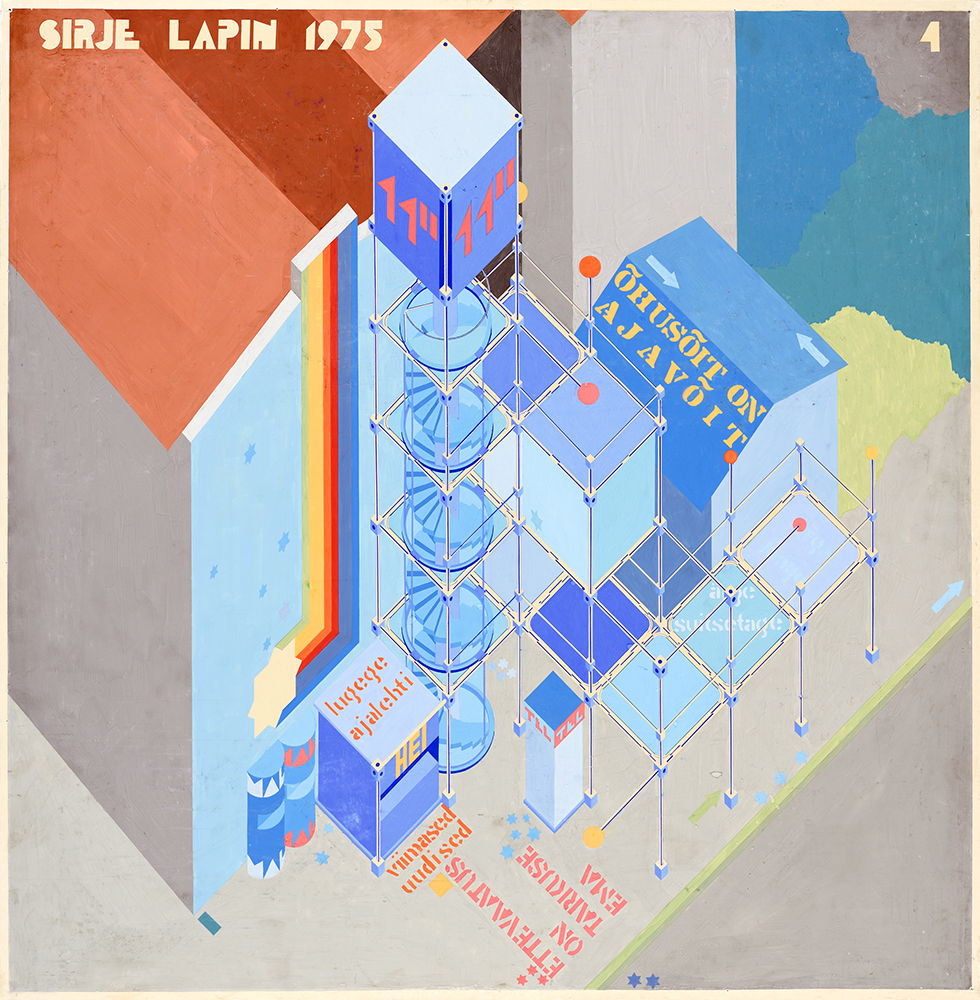

Sirje Runge, 1975. EAM 4.17.1

The images show different visions for enlivening the urban space of Tallinn. Designer Sirje Runge (Lapin 1969–82) submitted this design as her diploma work at the Estonian State Art Institute. The goal was to propose new ideas to bring citizens and contemporary city closer together in an artistic manner by integrating new technical landscape forms into the urban space. Upgrading the monotonous city became an unlimited field of work for young creatives against the backdrop of the official Soviet architecture that favoured repetitive environments. In her vision, new elements were introduced to the city and the colour schemes added to the housing. The visions were of three types: the first (p. 1 and 2), supergraphics for the façades; secondly, audiovisual communication centres – the artist saw in those open and accessible spaces a new meeting places for the community and where advertisement also plays its role. The latter (p. 8 and 9) introduced conceptual objects such as steel box that governs a natural object and a clock mechanism situated at the main square in Tallinn. In that sense, such irrational objects placed in the industrial city would bring human and city closer together. Sirje Runge gave the works to the museum as a gift in 2003. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1970s, designer: Sirje Runge, Tallinn

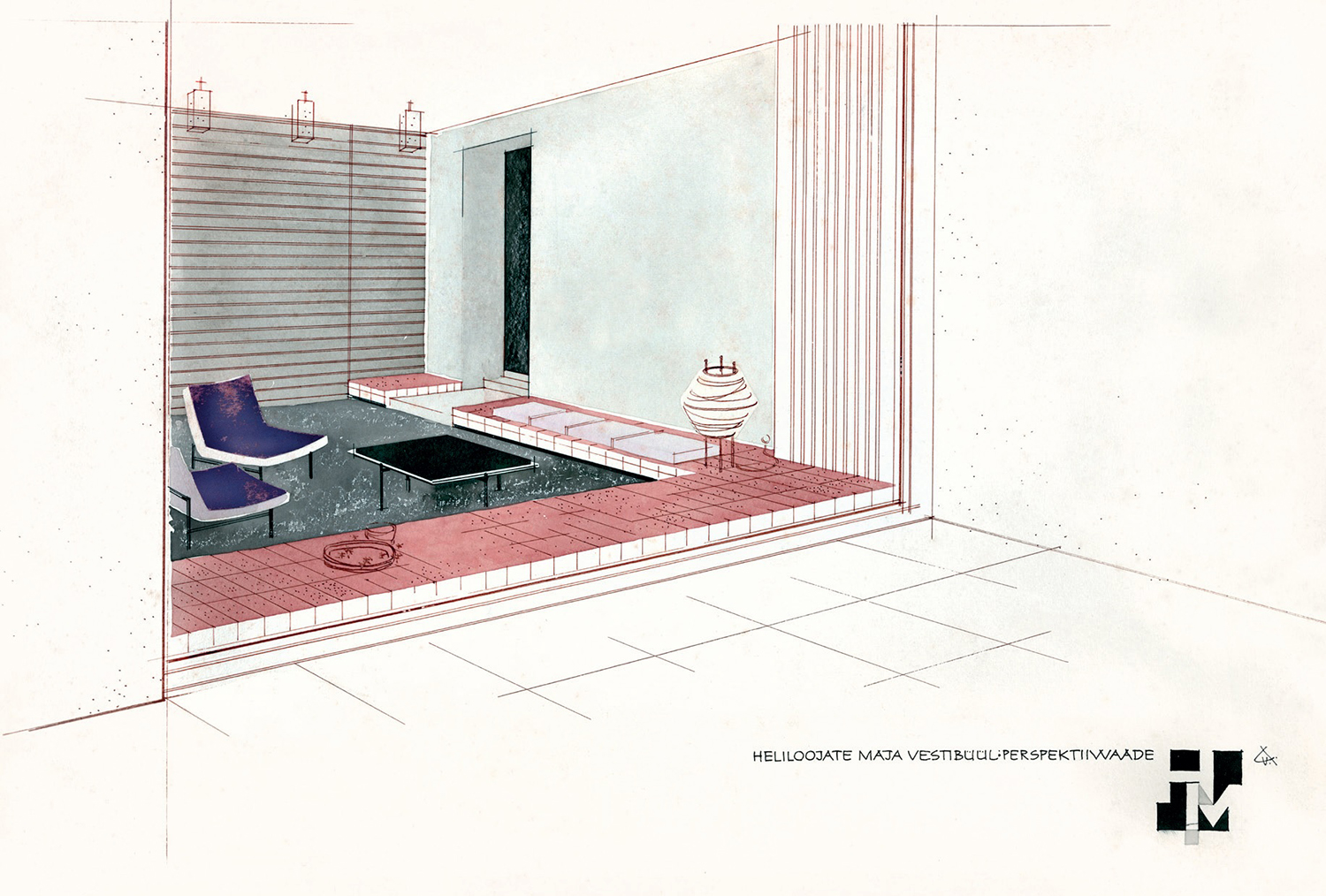

Interior design of the Composers’ house in Tallinn

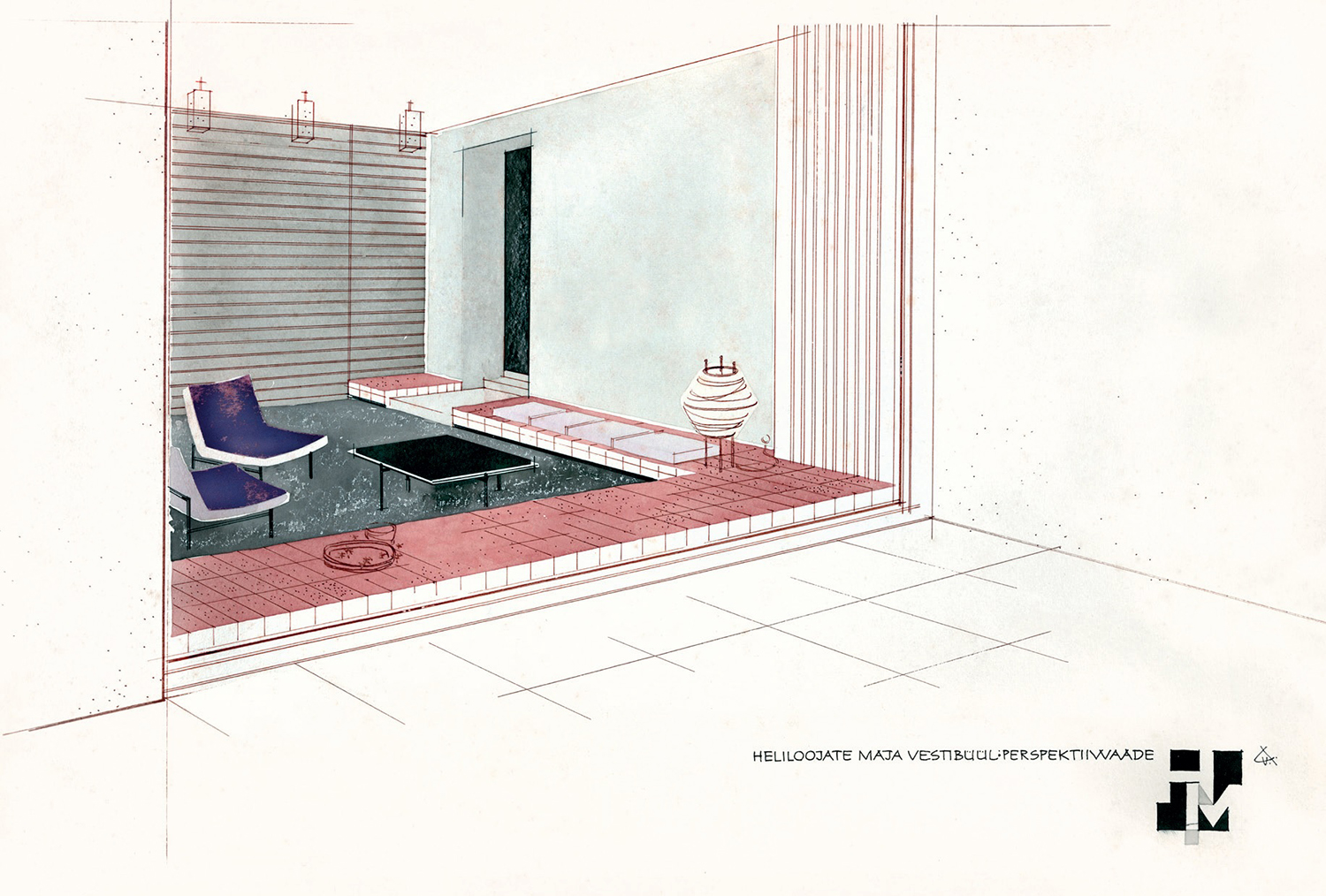

Vello Asi, ca 1960–1964. EAM 4.14.4

The drawing by interior designer Vello Asi depicts a view of the vestibule of the Composers’ House (architects Udo Ivask and Paul Härmson, completed 1964) located on Lauter Street in Tallinn – straight from the street through a big window. The aerial-looking interior with eye-catching low-sitting furniture is designed in the spirit of the 1960s. As was characteristic of the era, the interior designers picked up pointers from Nordic architecture literature that had just become accessible. This new approach to interior design valued open space, horizontal lines and light furniture that could be moved around with ease; it also favoured an inclusive environment to facilitate spending time in passable rooms. The drawing made with ink and watercolours was acquired by the museum in 2017. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1960s, interior, interior architect: Vello Asi, Tallinn

August storm in architecture

Avo-Himm Looveer, 1982. EAM K-48

The massive development of whole areas of prefabricated apartment houses in Tallinn during the 1970s and 1980s questioned the relationship between the new dwelling districts and the historical layers of the city. In criticisms of these general trends, it was suggested that architectural additions in a good living environment should consider the plurality of the urban fabric. In Avo-Himm Looveer’s work, monolithic elements seem to be sinking in the sea, with the skyline of Tallinn’s Old Town in the background, referring to the rapid development of Lasnamäe. In the architect’s vision this development moves beyond the boundaries of the residential zone and shows the artificial environment on a global scale. Its destruction by the forces of nature, on the other hand, refers to a breakthrough in how architecture is considered. The watercolour was acquired in 2010. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1980s, architect: Avo-Himm Looveer, Tallinn

Interior design of the Tallinn Town Hall

Leila Pärtelpoeg, 1973–1978. EAM 4.3.7

During the renovation of the oldest Gothic town hall which has been preserved in Northern Europe (completed in the beginning of the 15th century), a competition was held to find a fitting interior design for the historic surroundings. Some of the decision-makers believed the winning solution by interior architect Leila Pärtelpoeg with its heavy black furniture, high gloss doors and copper lamp globes to be much too competitive with the historical legacy. Others, however, saw the tension between new and old as an expected means to invigorate the room. The drawings depict medieval festivities in the trading hall and the guild-hall with historical chandeliers and side reliefs. Leila Pärtelpoeg donated nearly 50 drawings of the furniture and interior design to the museum in 2000. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1970s, interior, interior architect: Leila Pärtelpoeg, Tallinn

Competition entry for the observation and water tower in Mustamäe

Mart Port, 1962. EAM 52.2.11

The quality of the entry submitted for the competition for the observation and water tower that was due to serve the Mustamäe district in Tallinn lies in its pure technically engineered form. The modern concave roof of the lookout platform was possible thanks to the use of reinforced concrete. The area was under intense development at the time: the ski jumping tower on top of a hill slope in Mustamäe had been completed a year earlier and there were plans to build the campus of the university of technology at its foot. The perspective view shows an architectural drawing style that was common at the beginning of the decade where the classical watercolour and ink drawing has been completed using a wide dark-coloured felt-tip pen. The tower was never built. The drawings from Mart Port´s home archive were given to the museum by his family. Text: Sandra Mälk

Veel: 1960s, architect: Mart Port, Tallinn